|

Sherrill Grace,

"Inventing Mina Benson Hubbard: From her 1905 Expedition

across Labrador to her 2005 Centennial (and Beyond)"

(page 6 of 7)

With the outbreak of WWII, sales of A Woman's Way stopped and

the book went out of print. Outside the tiny community of Northwest

River, Labrador, Mina Benson Hubbard was forgotten for several decades.

But when attention began to refocus on the 1903 tragedy of the first

Hubbard expedition in the 1980s with Davidson and Rugge's book Great

Heart: The History of Labrador Adventure (the epithet "great heart,"

by the way, was Mina's name, borrowed from Pilgrim's Progress,

for George), Mina once more entered the stage, albeit in a very minor

role as the pathetic widow, as the stubborn and secretive competitor to

Dillon Wallace, or as the older woman out to seduce the handsome George.

Other writers to invent Mina have been Margaret Atwood, Pierre Berton,

Clayton Klein (his Mina is a sex-starved widow, and he passes off

fictional letters as real ones), the feminist canoeists Carol Iwata and

Judith Niemi, who did the George River in the early 1980s, Lynn

Noel, who romanticized Mina as a type of Pauline Johnson paddling her

own canoe, in a 1999 song collection called A Woman's Way, Songs and

True Stories of Northern Women Explorers, and the British journalist

Alexandra Pratt who attempted to repeat Mina's expedition with an Innu

guide in 2000, but failed and had to be air-lifted out. She published

her book, Lost Lands, Forgotten Stories: A Woman's Journey to the

Heart of Labrador in 2002. Despite their differences in perspective

and invention, from difficult widow to sexist thriller to feminist

celebration to faithful follower-in-the-steps-of who tries to repeat

Mina's journey, all these inventions, like the most recent

ones—mine, biographer Anne Hart's, and Randall Silvis's 2004 non-fiction

version Heart So Hungry—are by southerners, those who

Labradorians and Newfoundlanders label as "from away," American,

British, and Canadian. However, in 2005 that changed. On the centenary

of her expedition, the tiny community of Northwest River (population

500), assisted by Memorial University's Centre for Labrador Studies,

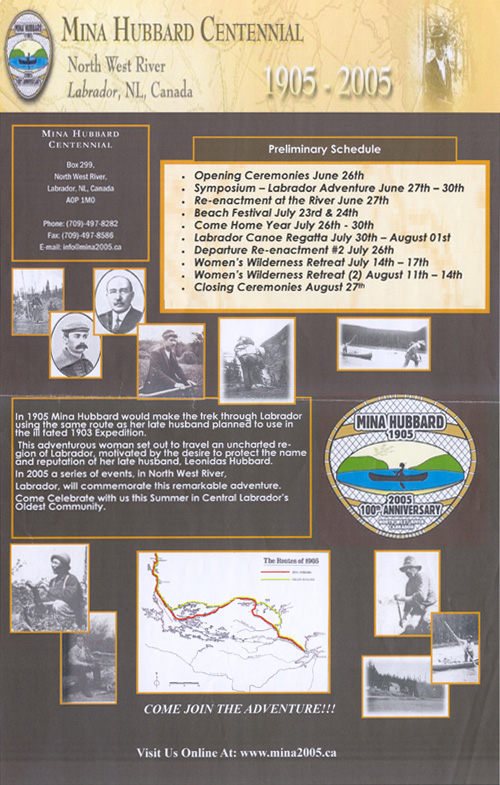

hosted the Mina Benson Hubbard Centennial (see Illustration 6). Many of us

from away were invited guests, but finally the northerners were going to

get to tell their stories about Leonidas, Mina, Wallace, George, and

their own ancestors who had rescued the 1903 survivors or who had been

on Mina's expedition. It is to these people and their inventions that I

want to turn now.

Illustration 6 The 2005 centennial celebration was organized

by the people of Northwest River, and a display about her expedition is

housed in the former Hudson Bay trading post that now serves as the

region's museum.

First, I must stress the fact that Mina Hubbard is a legendary

figure, along with the men—George, Leonidas, and Wallace—amongst the

"liveyers" (mixed race settlers, not Innu) of Northwest, but she is

especially cherished because they see her as having respected them in

ways that the white men from away rarely did. They also cherish her

because of the sensitive ways in which she responded to their beloved

Labrador.[5]

And like human beings anywhere, although with what I see as

more generosity of spirit, they have to this day a great sympathy for

her personal tragedy, her courage, and her tenacity; for many of them,

Mina's story is a love story—about her dear Laddie and about

their northern home. The centennial of June 2005 had four main

components: a conference on Labrador exploration; a re-enactment of

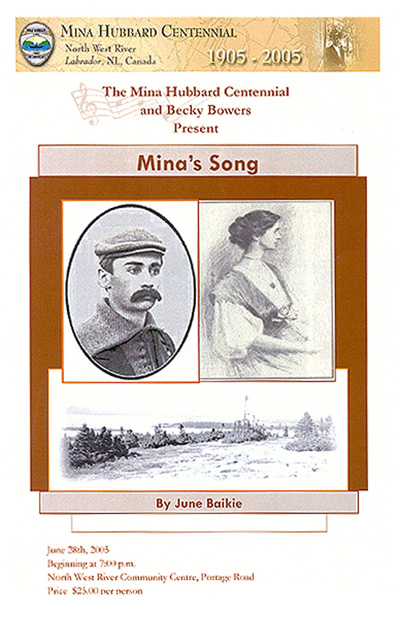

Mina's expedition setting forth (see Illustration 7); an original play by

Northwest's resident writer, June Baikie, and a film: everything done in

the re-enactment was being filmed as it happened, visitors and locals

were being interviewed during our few days there, and the film crew took

considerable footage of the Grand River, the community, and the

surroundings. Some of us were also flown—by the local airplane

company—over the rivers that feature so dramatically in Leonidas's death

and Mina's success. Many, many things impressed me during this northern

adventure, my first to Labrador, but the one I found most moving was the

staging, in the local community hall, of Baikie's play "Mina Song" (see

Illustration 8). Perhaps because I am an English professor who teaches drama;

perhaps because Mina's grandsons were also in attendance; perhaps

because descendants of those people who had known Mina were performing

in the play; perhaps because Baikie's invention of Mina resonated with

my own; and perhaps because I finally sensed that I had come very close

indeed to something emotionally true and symbolically important by

witnessing this production, perhaps for all these reasons

together, it was the play that made the biggest impact on me. This was

no professional theatre event, but it was valid and genuinely local.

Attending it was a form of field work, for a literary scholar, because I

was watching northerners take ownership—which they had never doubted

they always had—of their own story (see Grace 2006). Here was a

community performing its own myth, living what Pierre Nora calls a

milieux de mémoire. No one from away could do this.

Illustration 7 The opening event of the 2005 conference was

a re-enactment of Mina's embarking on her expedition from the shore in

front of the Hudson Bay trading post in Northwest River. Local

townsfolk dressed in period costume and gathered on the beach to watch

as members of the community, playing the roles of their forebears,

loaded the canoes in preparation. Martha MacDonald played Mina. Others

in the crowd were, like myself, invited conference guests who performed

as witnesses.

Illustration 8 This program is for June Baikie's play "Mina's

Song," which premiered in the local community centre in June 2007. The

play has gone on to have two further productions.

Of course, I am aware of the problematic status of the riverside

re-enactment with Martha MacDonald playing Mina and I acknowledge the

virtual nature of this representation, just as I recognize the

wonderfully imaginative creation of Baikie's Mina. And I shall be

fascinated to see what the filmmaker, Ann Henderson, does with all the

footage her cameramen got of the re-enactment, the conference itself,

and of the participants whom she interviewed. Nevertheless, the play

stands out for me because in it Baikie stayed close to the known facts

of Mina's life and death—even to having a train kill her before her

grandsons' eyes—while at the same time making a powerful contribution to

the northern discourse of Labrador. Her Mina, who adored her

Laddie—as the title song indicates—dies because she thinks she is going

back to Labrador to explore; her Mina calls out as she steps in front of

the train: "I am coming Laddie," coming, that is, into the realm of

death but also home to the northern landscape in which the

historical Mina constantly felt and saw her husband's spirit.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7

Next page

|