|

Sherrill Grace,

"Inventing Mina Benson Hubbard: From her 1905 Expedition

across Labrador to her 2005 Centennial (and Beyond)"

(page 2 of 7)

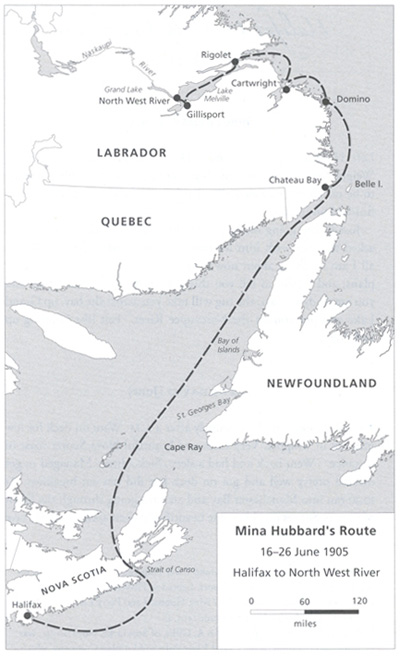

Mina hired George Elson, who was of Cree/Scots descent, to be her

chief guide and together with three experienced native men they left the

tiny fur-trading post of Northwest River, Labrador, in June 1905 to make

the six-hundred-mile trip through the interior and north to the George

River post on Ungava Bay. This well educated, white, middle-class, very

attractive widow of thirty-five, set out alone, with four non-white men,

on a journey that would take her far away from all the watchful eyes,

constraints, prejudices, and taboos of her society. She would be out of

sight (notably by white eyes) for almost seven weeks. However, the Mina

Benson Hubbard—elegant, ladylike, demure—as she was depicted in the 1907

portrait by Joseph Sydall (see Illustration 2), was the same person as the

happy, free, active woman who strides towards the camera on her Labrador

trail in the summer of 1905 (see Illustration 3). Both images were reproduced

in her book, and when I reflect on these two images I wonder who the

real Mina was and how the free spirit on her Labrador trail managed to

squeeze herself back into the corseted, decorous lady. It was

reflecting on such apparent contradictions that caused me to start

thinking about the concept of invention because the quick answer to my

question—who was the real Mina?—is that there were several Minas and

that she herself discovered, or invented, some of them during her

expedition. The process of invention had begun well before her book

appeared in 1908.

Illustration 2 This formal portrait of Mina Benson Hubbard

was created by British artist Joseph Syddall in 1907 and used as the

frontispiece in the Murray edition of A Woman's Way Through Unknown

Labrador. Murray also used Syddall's picture of Mina in marketing

brochures for the book, thus 'selling' her as a lady and her expedition

and book as respectable.

Illustration 3 This photograph of Mina on the trail in

Labrador in the summer of 1905 was almost certainly taken by George

Elson. Mina included it in her book.

Today Labrador is an official part of Newfoundland, the last province

to join Canada in 1949, but at the end of the 19th century it was remote

indeed, part of the British Empire, and serviced—minimally—by the

British supply ship Pelican which made one annual summer visit to

the coast and as far into Hudson Bay as Ungava. The Montagnais and

Naskaspi First Nations, now known collectively as the Innu, were

virtually untouched by white civilization, and the interior of Labrador

had been incompletely, and inaccurately, mapped by Arthur Low of the

Geological Survey of Canada. In the racist rhetoric of the day—a

rhetoric subscribed to by most northern explorers but not by Mina—these

tribes and their way of life were objects of curiosity, the stuff upon

which to make a reputation, stone age people for white men from the

south to discover. One of the key reasons for the failure of

Leonidas's 1903 expedition was the map; he could only rely on Low's

partial and inaccurate cartography and he took the wrong water route.

Among the other reasons for his failure and death were his lack of

appropriate supplies and gear, an early winter, and an unwillingness to

listen to the advice of his non-white guide George Elson. Mina made

none of these mistakes. She set out, as Leonidas had done (and as

Dillon Wallace was doing again at exactly the same time, in June 1905),

from the Northwest River post, she found the correct river route up the

Naskapi River to Lake Michikimau and then north on the George River to

Ungava (see Illustration 4).

As she went, she took the measurements that

enabled her to redraw the map of the Labrador interior; she took

hundreds of photographs of the country, its native people, her guides,

for whom she had the utmost respect, and their expedition work; and she

wrote almost daily in her journal. She did not have to do any of the

heavy, dangerous work of poling, packing on portages, or paddling, but

after her return unknown Labrador was unknown no longer.

Contemporary maps of Labrador and Atlantic Canada provide some sense of

how the area looks now (see Hart et al); however, a mere map cannot

capture the significant changes that have been made from the time of

WWII to the present by white settlers, developers, and politicians.

Illustration 4 Mina published this version of her map of

Labrador with one of her articles. On it she indicates her correct

route running north of A.P. Low's mistaken mapping of the river.

Mina would go on inventing herself after her return from Labrador by

giving public lectures, writing essays—scientific and popular—and

publishing her book. She remarried in England, raised three children

and worked for the suffragette movement; she returned to Canada

frequently and once, in her sixties, traveled north for a reunion with

George Elson. Labrador had become part of her, as the announcement for

a 1938 lecture indicates: the lecture, given at today's University of

Guelph was part of a tour she undertook that year and she is described

in the advertising as a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and as

the successful explorer of Labrador (see Hart, 411). According to her

children, she was an austere presence who would regularly set forth on

long walks by announcing that she was going off to explore, and it was

on the last of these explorations that she was struck and killed by a

train, not far from her home in England, at age eighty-six. Today a

commemorative plaque has been erected beside the road in front of the

original Ontario farmstead where she was born and grew up, but that is

only one visible reminder of who she was.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7

Next page

|