|

Sherrill Grace,

"Inventing Mina Benson Hubbard: From her 1905 Expedition

across Labrador to her 2005 Centennial (and Beyond)"

(page 3 of 7)

Just trying to summarize Mina's life story and her connection with

Labrador reminds me forcibly of how invented my version is—I have left

out so much, selected what I see as important, and emphasized what

interests me. In order to prepare my edition of her book, I found it

necessary to recreate, as best I could, her time and her place, to

listen to her voice in her expedition diary and in those few letters

that survive. But I could not transform myself into an Edwardian woman,

and Mina Benson Hubbard should not be viewed exclusively—or

uncritically—through my late-20th century/early 21st-century feminist

eyes. As I have continued to discover from my work on Mina, my book on

Canadian painter Tom Thomson—called Inventing Tom Thomson—and now

through my writing of the biography of a contemporary Canadian

playwright, Making Theatre: A Life of Sharon Pollock, the very

act of narrating a life story, however scholarly and factual, is a

re-creation; it is never and cannot be an ur-text, an original, the

Truth. Moreover, when a continuous line of such narratives begins to

coalesce around a once-living, historical figure, the story becomes more

and more sedimented in layers of interpretation, more complicated by the

story-tellers' self-legitimating strategies and truth claims. And the

subject of all this narration—the person who motivated or inspired the

story in the first place—becomes larger than and other than him- or

herself. The person becomes a symbol, or a legend, or a myth, or, as I

prefer to think of it—an icon.

As I argued in Canada and the Idea of North, over time and

with a critical mass of repetition, a discourse emerges around a

particular person or event or place, which thereby becomes invested with

crucial meaning for a family, for a group of people, or even for a

nation: this one story acquires significance; it comes to stand for

something much larger than one life or one accomplishment (or death, or

sacrifice, etc). I well remember being challenged about this term

"invention" when I used it in a lecture on Tom Thomson. My audience was

from Owen Sound, Ontario, Thomson's home town; we were in the Tom

Thomson Memorial Art Gallery (where a very definite investment in his

story exists), and my listener felt the term invention sounded

pejorative. I think he felt that I was fiddling with the facts, making

up stuff, lying, and I know he believed that only one story about the

famous painter could be true. But I see nothing pejorative in the term

invention; to the contrary, I see much greater ideological,

psychological, and possibly even political power residing in the

inventing process than in a set of bare facts. What interests me is how

this process works, how I can locate and describe it (with what

scholarly tools and theoretical concepts), and what meanings a

particular iconic invention produces. In the following discussion I

describe how and why I think this woman called Mina Benson Hubbard, or

Mrs. Leonidas Hubbard, Jr., or Mrs. Mina Ellis (her second husband's name)

is becoming a Canadian icon through her many, and on-going, inventions.

In Canada, and in this case of Mina, there are three critical

determinants at work: first, the basic story concerns the North,

a vaguely defined, real yet mythical place of enormous symbolic and

practical value to the country, and a place very much in the public eye

in the early 21st century; second, the central figure in the story is a

woman on an expedition into a part of the north that remains foreign,

mysterious, even exotic to the great majority of Canadians; and third,

the verifiable facts of the story include a tragic death, a love story,

and a survivor story. Just summarized like this—mysterious North,

dangerous expedition, young woman, tragic death, faithful love, all set

in 1905—would make a person eager to know when the film will be made,

and it so happens that one film has already appeared and at least two

others are underway.[3]

The inventing of Mina Benson Hubbard is rapidly

becoming cultural business.

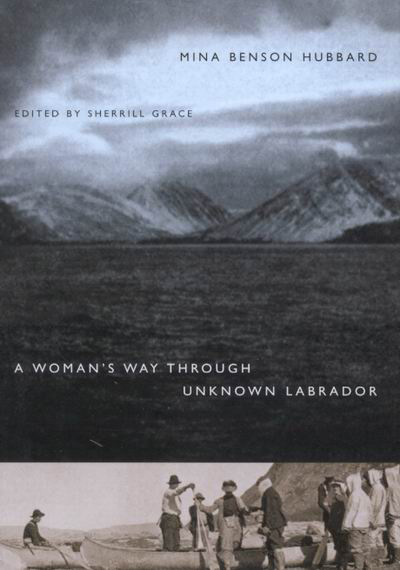

Illustration 5 This striking jacket was designed by David

Drummond for the 2004 edition of Mina's book. McGill-Queen's University

Press included all Mina's illustrations and a full, fold-out

reproduction of her map, which is glued into the binding and can be

opened out for readers to follow her trail as they read her

text.

In 2004 my new edition of Mina's A Woman's Way Through Unknown

Labrador was published and my publisher, McGill-Queen's University

Press, or rather their designer, captured and capitalized upon many of

the discursive elements I have mentioned to market the

book (see Illustration 5):

there is the romantic, mysterious, beautiful yet overpowering

northern landscape; there is the woman stepping out of her canoe, out of

another time and place, and into our 21st century sights. Before a

reader even opens the book, Mina has already been placed in a set

of concentric and overlapping paradigms that resonate for Canadians and

for others who love the North. But there is an important caveat to make

about this dust jacket image because readers/buyers are being tricked by

the woman whose arrival at Ungava appears to be captured on camera. The

photograph at the bottom of the dust jacket was staged. When Mina

actually arrived at the end of her expedition, on the mudflats of the

George River, no one was waiting with a camera. The factor, Mr Ford,

and his wife, had heard vague rumours that she might be making this

expedition, but they had no positive information—there were no

telephones, cell phones, Blackberries, or couriers in 1905, and the

interior of Labrador was just that—interior, uncharted (for white

people) territory. What's more, Mina had made excellent time and

arrived days before she could have been expected. But she knew that to

prove her arrival she would need a record of it; she also knew full well

that no man would believe a woman could possibly complete such an

expedition, unless there was visual proof of the fact, and that no white

man would take a native man's word on it. Wisely, she arranged this

photograph and the people in it so posterity could see her stepping

daintily out of her canoe, always already a lady despite her suspicious,

salacious time in the wilds.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7

Next page

|