|

This article was originally published in Nancy Campbell's Annie Pootoogook, published

by Illingworth Kerr Gallery in Calgary and Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown in 2007.

It is reprinted with permission.

Inuit Art and the Limits of Authenticity

by Debora Root

Several years ago I purchased a print by Cape Dorset Pudlo Pudlat

entitled Imposed Migration (1986). In this image three animals

dangle by their necks as they are carried away by a military helicopter.

As I gazed at the polar bear ensnared by the noose around its neck, the

gallerist explained that Inuit work depicting contemporary objects, such

as snowmobiles or helicopters, was very much a minority taste. Most

buyers preferred the sublime images of the natural world and traditional

ways of life that Southerners have come to associate with Inuit art, she

said, because there are more authentically and recognizably "Inuit." For

such buyers, authenticity resides in what is sometimes termed the

"ethnographic present," a timeless place untainted by modernity.

Twenty years later, there would seem to be more openness to the

contemporary images explored by some Inuit artists. Exhibitions of Annie

Pootoogook's work at the Illingworth Kerr Gallery, Documenta in Kassel,

Germany and The Power Plant, Toronto, and her recent 2006 Sobey Art

Award, suggests that Inuit art is beginning to be understood as a vital

aesthetic practice rather than a static, culturally determined artifact.

That the pace of Inuit art within the art world remains a topic of

discussion indicates the persistence of older ideas of what this work is

or should be. And many Southerners continue to believe that images of a

pristine Arctic are somehow more authentically Inuit than Pudlat's

machines or Pootoogook's video games.

Within a contemporary art paradigm, however, "authenticity" means

something rather different. Here, disturbing images tend to be seen as

more "real" than beautiful ones, in part because the artist's job is to

strip away the dishonesty and pretension of modern society. Think of

Warhol's car crashes; think of all the recent work that seeks to shock

the viewer into a different way of apprehending the world.

"Authenticity" is a floating category, able to migrate and legitimize

or de-legitimize certain kinds of images. If some consider Inuit art

inauthentic when it includes recognizably Southern elements, others have

suggested that the art is itself inauthentic because it is a constructed

tradition. No art market existed in the North prior to James Houston's

efforts to create one in the 1950s and 60s. The argument can be reduced

to something like this: white impresario travels North with a plan; the

work is marketed in the south as "authentic," even if there was no

pre-contact tradition of large-scale sculpture or printmaking. The work

is purchased primarily by those seeking an idealized representation of

First Nations experience. Meanwhile, colonialist structures and

institutions remain, masked by images of a pristine past.[1]

Of course, what is missing from this formulation is the work itself.

In this view, Inuit art cannot be an "authentic" expression of an

artist's aesthetic vision because it is market-created (unlike the New

York art world, one assumes). It is bad enough that a concept of

inauthenticity is sometimes used to de-legitimate Northern art

practices, but we would do well to remember that this category has also

been employed within the Canadian and U.S. legal systems to undermine

Fist Nations' land claims. At times the authentic is used to denote a

traditional way of life or quality than someone thinks should be

retained, and at other times it is used to suggest a gritty contemporary

quality. The question always remains of who is deciding what is

genuine.

The history of the Inuit image-making, and its reception in the

South, thus raises questions about what kinds of images come to be

valorized in the Southern marketplace, and about the cultural and

aesthetic expectations n the part of consumers. Printmaking and

soapstone carving originally were designed to bring Northern communities

into a cash economy, and to generate images that would stand for the

Canadian identity in the international area. Because Southern buyers

wanted access to another world, traditional images sold well.

In this sense it is true that Inuit art is a constructed tradition.

Yet Inuit drawing, printmaking and soapstone carving quickly exceeded

the bare fact of their origins, and became conduits through which

Northern artists could express aesthetic and social concerns in new and

meaningful ways. The constructed traditional became real through the

lived experiences and aesthetic practices of the artists. And because

Northern society exists in the present, some Northern artists make

images of contemporary realities.

But the reception of Inuit art in the South has been slower to

transform. Until very recently, Inuit art remained in a category by

itself, a subset of First Nations art, not quite traditional, not quite

modern, and rarely understood as contemporary. Southern buyers of Inuit

art tended not to follow contemporary art; similarly, those interested

in contemporary art were relatively indifferent to Inuit art. Inuit art

was a separate market, firmly sited in an anteroom of Canadiana and

rarely stressed in Canadian art history curricula. Although artists such

as Annie Pootoogook are breaking through these categorical strictures,

many of the old assumptions remain.

Even if nearly everyone can appreciate the beauty of such work as

Kenojuak's iconic Enchanted Owl (1960), there has been a tendency

in contemporary are circles to dismiss Inuit art as something akin to

tourist art. I used to feel slightly sheepish about liking Inuit art; it

was something for corporate offices, or Canadian embassies in Europe. I

can also understand why many might be disturbed by the mechanized

intrusion of Pudlat's helicopter into the natural world. But, as a

contemporary image maker, Pudlat had something to say about the fantasy

of an untouched landscape and the reality of Canadian government

policies. And utilizing a difficult image to unmask received ideas is

something we would expect to encounter from a non-Inuit contemporary

artist.

A recent text asserts:

Producing art has enabled many Inuit to pursue a relatively

traditional lifestyle . . .. While Inuit artists have been prompted and

influenced to produce art by southerners and southern institutions, they

have nonetheless managed to imbue their art with traditional values and

memories of life as it once was . . ..[2]

In one sense there is nothing wrong with these remarks. But, written

in 1998, they draw the reader's attention away from the contemporary

context of Inuit image production and towards the past. The reiteration

of a notion of the "traditional," which in fact does not exist in the

way many Southerners imagine, becomes a way of manipulating the viewer's

expectations.

Native communities have often been presented, in films and ad copy,

as existing in an eternal past or, if attempting to negotiate the

present, as somehow more firmly tied to or affected by the past than

non-Native communities. Each community has a particular relation to

history, and colonial histories in Cape Dorset will differ from those in

Toronto, but these specificities ought not be dependent on an unexamined

notion of a timeless past. This brings us back to the category of

authenticity, and how perceptions and expectations of a traditional,

unchanging North are structured.

Part of the problem lies in the way the cultural difference of Inuit

society functions to assuage anxieties about change in Southern

cultures. If, in the case of the North, "authentic" is believed to mean

the pre-contact world depicted in Inuit art, this concept serves to

eliminate social space; politics disappear, so there is no necessity for

excavating history, there is no responsibility for righting injustices

or supporting land rights. There is no guilt. The Southerner can mourn

the loss of a pristine natural world without thinking about why this has

happened, and without examining how and why similar losses have occurred

in the South, and the costs of these for everyone. Within the art works,

certain images have come to stand for this cultural difference—a seal

hunt, a shaman, a dancing polar bear—which in turn stand for a

generalized authenticity. In fact what is being consumed is

authenticity, and the consequence of this simulacrum of difference is

that we need not ask why these are the images we want to see. But if

something is deemed "authentic," something else must necessarily be

inauthentic by comparison.

It is long past time to call into question the familiar, overarching

categories that structure our understanding of art, such as Inuit art,

outsider art, Northwest Coast art, tourist art, Canadian art, Western

art. If we wish to classify art practices, different criteria might be

more to the point, in particular a notion of "school," which suggests a

group of artists addressing similar concerns and styles in their work. A

contemporary landscape school might encompass works from several

origins; what holds the category together is the approach to a subject,

not the ethnicity of the artist.

As a category, "Inuit art" is simply too broad, and too culturally

determinant, implying a unified aesthetic vision that does not exist

even within work that takes traditional life as its subject. For

example, the minimalist, early drawings of Luke Anguhdluq utilize white

space to convey bareness in the Northern environment, while Simon

Tookoomee's highly colored images burst forth in an exuberant vision of

the spirit world. And "Inuit art" is too restrictive a category for the

work of Annie Pootoogook, whose contemporary vision transcends older

limitations.

The inadequacy of "Inuit art" as a category is apparent in the unease

artists such as Pudlat or Pootoogook provoke when they address

contemporary issues. In reality, Inuit art has always crossed many

categories; at once a pricey souvenir of a visit to Canada and a

nationalist symbol in embassies, it often exceeds both these limited

expectations. A whiff of the ethnographic remains in some images, but

even so, such work rarely falls into kitsch, even in pieces one sees in

hotel gift shops. The fact is that Inuit art is often very good, and at

times extraordinary, something most of us do not expect from tourist

art. The range of the work reminds us that there is no such thing as a

pure state of cultural authenticity. Culture has always been mixed,

contradictory, difficult.

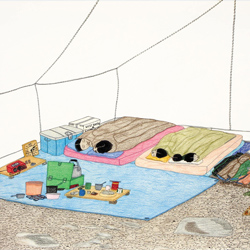

Pootoogook's work illuminates many of these issues, reminding us

again that one of the reasons people make images is to exemplify the

world they inhabit, and to show how this world works in new and

unexpected ways. Contemplating Pootoogook's images of Northern life, the

viewer sees that the old, discrete categories "Inuit art" and

"contemporary art" are no longer relevant.

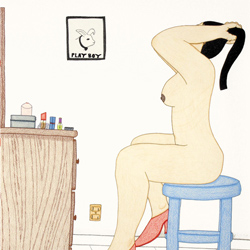

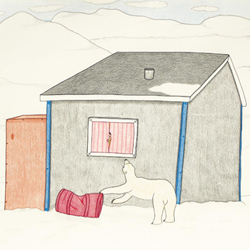

As in much contemporary art, there is something profoundly disturbing

about her images of the everyday, where the figures seem to float in

space as they go about their business. One looks not only because of a

fascination with the mix of Northern and Southern elements, but because

the images oscillate between anomie and community as they interrogate

the individual's relation to material culture. Some viewers understand

Pootoogook's work as exemplifying a "culture clash" between North and

South. For me, this does not quite ring true. Rather than a portrayal of

Northern and Southern cultures as separate, isolated entities, what we

see in Pootoogook's images is an integration of elements, an integration

characteristic of lived experience. Her work presents culture as a fluid

entity, and makes it very clear that Southern elements are being taken

up and interpreted actively, rather than by passive recipients or

victims of colonialism. Yet that history is there, situated in the

sometimes difficult lived culture she depicts, yet by no means

ethnographic. And sometimes her vision is ironic, sometimes not.

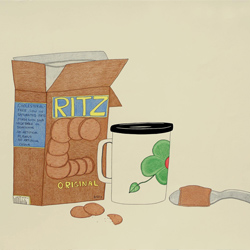

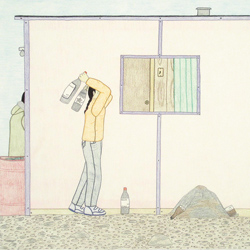

Contemplating Pootoogook's images of video games, television, and

anxieties about monthly bills, the non-Inuit viewer is confronted with

his or her assumptions about life in the North. If those of us who live

in the South wish to imagine the North as an essentially natural world, we

find it difficult to accept that Inuit societies are in fact modern.

Yes, we might recognize that Northerners have Ski-doos and perhaps some

canned goods, but when we think of the unspoiled Arctic, Jerry Springer

is not what we have in mind. I can't help but feel that what is at stake

is old, colonialist belief in the so-called benefits of civilization.

Images of pure, unmediated space allow us to maintain that fiction.

Pootoogook reminds us that everyone enjoys pop culture, and in doing

so refuses to allow a paternalistic understanding of life in Cape

Dorset. Yet her work also manifests an oscillating unease with the

relations between pop culture and the community, the family and the

individual, the natural world and machines, and the reality of social

problems in the North.

There is a moment near the end of Zacharias Kunuk and Norman Cohn's

film The Journal of Knud Rasmussen (2006) when shaman Avva says

goodbye to his spirit helpers. The spirits trudge across the ice,

weeping and wailing as they go. Avva has been forced to repudiate the

old ways because his starving family will be given food only if they

become Christian, which means breaking the taboos that allow spirits to

share space. We all feel Avva's loss, of the past, of an alternative to

capitalism, of other possibilities. We want to retain the idea of a

place where time stands still, where people live close to the land and

remain conversant with a magical world.

Most Southerners encounter Inuit culture through Inuit art, and

through the images of traditional hunting, old stories, and shamanism.

This is one reason why Avva's traditional family seems more "real" than

the Christian characters with their imperfect English, more authentic,

if you will, than the Inuit who have taken on Southern elements. And

this brings us back to what we imagine we are consuming when we refuse

to accept certain artists' productions as wholly contemporary, simply

because they are made by Inuit.

The Journal of Knud Rasmussen was set in the early 1920s, in a

past that from this distance can only be imaginary. Even in Avva's

family, Southern culture was present in the form of made items, and the

presence of the Danish anthropologists imply that many of the old ways

were already on their way out.[3]

As in the South, Inuit communities have changed and continue to

change, and this is reflected in the kinds of images produced by

Pootoogook, whose subject matter differs from earlier generations of

artists, such as her mother Napatchie Pootoogook and grandmother

Pitseolak. Inuit communities have engaged with Southern influences for a

long time. The idyllic images of hunting and other traditional ways

depicted in the first Inuit artworks available in the South exemplified

a world that was already under extreme pressure, in many ways no longer

existing as it once had even twenty years earlier. It seems likely that

a nostalgia for an older way of life was present on all sides, from the

artists to the collectors, and there are several reasons why government

officials and Southern collectors might wish to see images without

political unpleasantness.

But the point is not that the North has changed, but rather that the

South must be willing to see in a different way, and to begin to accept

Inuit artists as artists, without expectation of particular kinds of

images or a pre-determined cultural authenticity. If we delegate the

loss of the natural world to Avva, or to the past, or to Inuit artists

who are supposed to heal us with sublime images of nature, then we are

dooming ourselves to a false relation to the world. It seems evident

that contemporary art is almost by definition a hybrid form, whether the

artist comes from Toronto or Cape Dorset. The Illingworth Kerr Gallery's

presentation of Annie Pootoogook's work marks an important beginning of

this shift in perception.

Endnotes

1. See, for example, Kristen K. Potter, "James

Houston, Armchair Tourism, and the Marketing of Inuit Art," Native

American Art in the Twentieth Century, ed. W. Jackson Rushing III,

(London: Routledge, 1999). [Return to text]

2. Ingo Hessel, Inuit Art: An Introduction,

(Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre,1998), 11. [Return to text]

3. For a history of the Arctic, see Alootook

Ipellie, "The Colonization of the Artic," Indigena Contemporary Native

Perspectives, ed Gerald McMaster and Lee-Ann Martin, (Vancouver: Doughs

and McIntyre, 1992), 39-58. [Return to text]

|