|

Last Light: Antarctica

Last Light: Antarctica is a series of photographic works

shot in early spring of 2006 when I travelled to the Ross Sea region of

Antarctica for two weeks with the Artists to Antarctica program

sponsored by Creative New Zealand and Antarctica New Zealand. I arrived

one hundred years after the first Antarctic explorers headed off to the

South Pole and the centennial celebrations only seemed to me to

underline the shallowness, the brevity and the utter inconsequentiality

of the colonial project in Antarctica.

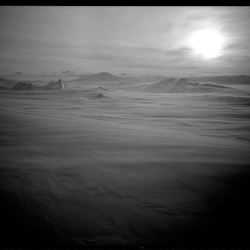

The Antarctica I found was an alien icescape—savage and

primordial—completely devoid of human objects, huge and oblivious but also

replete with signs of fragility, stress and potential collapse. The

photographs are at once epic in scale and antiheroic in their attention

to the cracks, crevasses, glacier faces and pressure ridges which

emerge, collapse and re-form in a rhythm tied to global climate systems

that are in turn linked to our own systems of consumption. They point to

a dark irony in the growing consensus that while efforts at colonizing

Antarctica throughout the twentieth century barely dented its icy

surface, our collective addiction to fossil fuels, acting incrementally

and from afar, has gnawed deeply into the ice structures that cover the

continent. The resulting unintended effect is antiheroic, grimy,

disintegrative and potentially cataclysmic.

My photographs borrow their gothic sublime aesthetic from nineteenth

century romantic landscape painting and do so to point out a troubling

shift in the human relationship to landscape. Edmund Burke regarded

sublime nature as awesome, overwhelming, humbling and simultaneously

invigorating in its offer of mortality glimpsed but not actualised. The

21st century viewer has an altogether more disturbing relationship to

the mountain, the thrashing ocean, the crevasse and the glacier. Now we

look at Nature askance and with guilt, aware that its grandeur has

become somewhat sullied by our modernity and privilege. What I hope to

reinvigorate with this work is the sense of terror that lies at the

heart of the sublime response. The large size of the prints gestures to

the massiveness and immersive quality of an earlier notion of the

sublime. The sense of personal crisis at the center of this former

sublime has expanded to include all of humanity. Now when we approach

the crevasse we no longer approach the possibility of our mortality

alone, but rather that of our species and potentially our biosphere.

This is such a terrifying idea that it fails to confer the rewards of

the sublime: it does not invigorate. We look askance because we cannot

bear to look nature in the face. My hope with this work is to invite

that direct look and to mobilize the terror it should provoke.

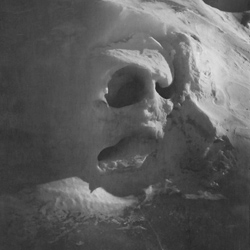

Polar Gothic

Last Light employs techniques of the past to chart

contemporary phenomena that will have enormous effects on our collective

future. The daguerreotype is an exquisite technique in which the

photographic image floats on the mirrored surface of a highly polished

silver plate. I used this technique to document signs in the ice:

fissures, flaws, pressure ridges and a screaming ice ghoul, a harbinger

that confronted me high in an icefall as I descended though a white out.

The daguerreotype requires a direct, physical imprint of light on

chemicals on plate that cannot be manipulated or faked through

post-processing. In a time of digitized mediation, the daguerreotype

offers analog proof of place: it is a sign and witness to the

continent's immanence and of its ruin. The daguerreotype was

essentially outmoded by the mid-nineteenth century invention of silver

halide emulsion. Because its decline preceded Antarctic exploration, it

is a mode of representation that has never been practiced on that

continent. In having done so now, I hope to draw my audience into a

conversation about modernity and obsolescence and the evidentiary role

of photography. Through these anachronistic artefacts I am inviting my

audience to invest physically in Antarctica, a place of unrivalled

importance and unfathomable strangeness that most of us will never visit

but which all of us continuously undermine. The intervention of the

"Polar Gothic" into the seemingly tame and managed modern Antarctica of

science is a revival of an earlier era's close relation to terror, but

also an embodying of the evil of global warming, which in a change on

the daguerreotype's obsolete force, opens up the volitional aspect of

ice, or the way Antarctica reveals itself as a

terrifying—and damaged—landscape.

The Dry Valleys and the Futility of the Colonial Effort

On our final weekend in Antarctica our group was flown by helicopter

to the Dry Valleys. It was a huge privilege to be taken there, but I was

overwhelmed by the trip. It was not until we returned to the base that

evening that I began to make sense of why I had found the dry valleys so

frightening and why the visit had left me feeling so bereft.

I had walked through one of the most lifeless environments on earth.

There was no liquid water and very little ice. The temperature was

around thirty degrees C below zero. The stone strewn ground had been

worn down by the action of wind over centuries until it resembled a

polished tiled surface. I saw no insects, no moss, no algae, nothing

green of any kind. There was very little in the way of bacteria. Nothing

in this environment could decay. We were admonished not to leave the

tiniest scrap of food behind because any remnants of our visit would

remain, intact and unconsumed for the next several hundred years. The

valleys are littered with the frozen remains of penguins and seals that

wandered off course to their deaths hundreds of years ago and have

remained there, unchanged, ever since.

There is life in the dry valleys, in the form of nematodes and

primitive lichens, but it takes a very trained eye and often the help of

a microscope to spot it. It is the kind of primitive, hardy life we

might, in moments of great optimism, hope to find on a planet like Mars.

And it is in the dry valleys that JPL technicians have found an ideal

environment to test-drive their mars rovers, the advance guard in a

widely fantasized post-global wave of colonization.

What became utterly clear to me during my visit to the Dry Valleys

was the futility of that brand new colonial effort and the essential

interdependence of climate and life. We could not have survived more

than two hours on that frozen desolate plane without the great stacks of

survival gear unloaded with us and we will not survive anywhere else. We

will learn to live here or we will die, all of us together. It is not a

sublime thought. It is so ugly it can hardly be thought at all.

|