|

Anne Noble is more than a photographer of the Antarctic: she is

discoverer of the visual history of the Ice. Noble has been on the

trail of the last continent from the vantage point of New Zealand for

some years now, and visited the Ice (as the New Zealanders call Antarctica)

on a tourist ship and as part of the NZ Antarctic program. As Gender

On Ice is published, Noble is the guest of the U.S. National Science

Foundation Artists and Writers Program, photographing the ever-shifting

ice.

Antarctica, to Anne Noble, begins in the imagination. Its medium has

been photography. As Noble states, ". . . our sense of the Antarctic comes

from the long tradition of 'heroic' photography . . . from wilderness

and tourism photography and museum displays. . . that reinforce images

we have already seen." For Noble this means that much of her Antarctic

photography takes place in sites off-continent, in tourist cruise ships,

museum installations, historic artifacts, traveling exhibits and

family-style entertainments such as "Kelly Tarleton's Antarctic

Experience," a well-known tourist attraction in Auckland, NZ, where live

penguins on display vie with life size recreations of the interior of

Scott's hut, down to the detail of the contents of the explorers'

bookshelves. Noble questions the formulaic power of Heroic Age

representation in re-photography. In her notorious rephotographing of

the Scottish 1902-04 national expedition's well-known image, "The Piper

and the Penguin," the kilted bagpiper still screams Scotsman on ice, and

the penguin, not so subtly tethered to a tambour, remains the Scotsman's

captive audience, now through layers of time and irony. Noble is

herself an Antarctic curator in the broadest sense, providing a cultural

history of Antarctic representation through her own substantial body of

work, as well as her editorial work in the 2007 special issue on

Antarctica of New Zealand Journal of Photography.

This engagement with how Antarctica is imaged, produced, and

circulated characterizes Noble's recent work. In 2006 Noble created a

suite of images and artifacts displayed at a New Zealand gallery that

played with both the commodification of Antarctica and the art market in

which her work on Antarctica inevitably takes on meaning and value, as

it circulates knowledge about the least capitalized place on earth.

Noble was inspired to create "Antarctic Shopping Party" when she came

across "mention of the organization Antarctic-Link, Canterbury. One of

their key objectives is to build a marketable Antarctic product-set for

Christchurch New Zealand, to help brand the city as a 'Gateway to

Antarctica . . .." Keeping in mind tourist shop creations such as

stuffed penguins and krill key rings, explorer logo mugs, T-shirts

and the like, Noble crafted consumables such as Antarctica shaped (iced)

cakes and cookies, a continent-shaped jigsaw puzzle, and CDs and video

tapes branded with the image of the continent—all for sale at the

gallery. Locked into the parody is a " . . . sadness . . . about the

desire and longing for that transcendental feeling of place and how it

becomes a thing we consume." As beautiful and enjoyable as Noble's

Antarctic objects may be for an audience, their appreciation is innately

linked to a sense of loss of the object of Antarctica, here so complexly

represented. In her "Whiteout" project, Noble engages another type of

loss, a visual one, as she points her lens mercilessly into Antarctic

icescapes that lack horizon, color fields, or any conventional markers

of place. Seeing Antarctica as Noble presents it in "Whiteout" becomes

as perilous an act as navigating the white expanse of the Ice.

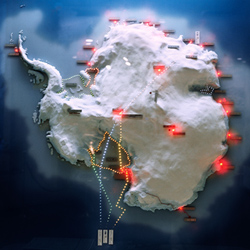

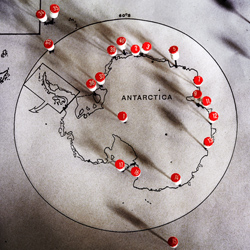

The ways culture has created to know and to interact with Antarctica

is most simply seen in the map, an economic object that both represents

and circulates Antarctica. Anne writes of her map series: "This

collection of maps points to the way visual colonization of place occurs

as a part of the way that we map, photograph, organise, define, and

interpret place." Expanding on the idea that photography is complicit

in the evolution of an Antarctic economy, Noble finds maps in obvious

and strange places. Amid plastic blow up world maps and other casual

ephemera, a chilling reminder of early corporate involvement appears in

the British Petroleum map of Antarctica from 1955. Following up a lead

from her stay at New Zealand's Scott base, a nicely preserved set piece

from the 1950s, Noble discovered the map in the archives of the

Canterbury Museum in Christchurch, NZ. The BP map is shaped as a board

game and is an accidental witness to the foundational, and taken for

granted, influence of petrochemical corporations in the creation of

Antarctic place.

Noble's Antarctic vision is so varied and deeply thought that it

reminds us of a most important and overlooked fact: Antarctica is not a

single or unified place. It is not timeless, or an empty signifier for

sublimity, or a culturally neutral notion of grandeur. Noble is more

interested in the ways "grandeur plays out in an artificial environment"

both on the continent and in other locations. Noble has pieced together

a global "puzzle" of multiple, competing, and even incoherent

Antarcticas. This inexhaustible Antarctica ultimately has no sure

origin or foregone end. Noble's remapped representational histories

have profound implications for geopolitics: who owns this place, or even

its image?

Statement by Elena Glasberg. All quotes from: "A Landscape

Brought to Light." The Age. 13 September 2008.

|