In this essay, I examine how queer Iranian American artist and activist Amitis Motevalli attempted to position the 2009 pro-democracy uprising in Iran in relation to the unfinished black freedom struggle in the United States. 1 I explore the potential for diasporic Iranian cultural production to reframe the U.S.-Iran conflict by engaging each national context as a site of ongoing battles for social justice and by projecting a vision of cross-racial solidarity from the margins of each society. Motevalli’s 2010 exhibit in Tehran, Here/There, Then/Now, on which I focus, reproduced words and images from the 1960s civil rights insurgency in the U.S. south in ways that made subversive connections between the lack of democracy in both the United States and Iran. By commissioning the first-known Persian translation of Fannie Lou Hamer’s 1964 speech at the Democratic National Convention, and by featuring this text in her exhibit, Motevalli countered Orientalist presumptions about whose voices should represent the “West” and which aspects of “Western culture” should inspire and influence the oppressed “East.”

Motevalli’s exhibit must be understood as part of a longer genealogy of affiliations between Iranian and black activists. Her work poses a queer feminist critique of the male- and often state-centered iterations of third-world anti-imperialism that arose during the second half of the twentieth century and that gave rise to significant, yet understudied, manifestations of Iranian internationalism. Working through this legacy, rather than against it, Motevalli’s exhibit intervened in debates over the meaning of freedom and democracy in Iran as well as in the United States, and reflected her alienation from the Iranian American mainstream and the frameworks that undergird much of Iranian American cultural production. Through her affiliation with Hamer, Motevalli charted novel routes of queer feminist cross-racial solidarity, hoping to provoke her audiences to view themselves and their movement through an internationalist lens. She approached this political vision through a transnational set of practices. She not only exhibited her work in galleries in the United States and Iran, but also mobilized aspects of Iranian and U.S. history in ways that engage the crises that both societies now face in ways that represent these crises as interrelated. Before further discussing Motevalli’s unique approach to making diasporic political art with Here/There, Then/Now, I first situate this essay within the field of Afro-Asian studies.

Out of Place, Out of Time

Until now, Iranians have been virtually absent from Afro-Asian studies scholarship, despite a rich history of joint organizing with African American and African activists in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. 2 This is in part because Iran, along with the rest of West and Central Asia, has been artificially severed from the Asian continent by area studies epistemologies and institutional practices. 3 Integrating Iran and the Iranian diaspora into scholarship on U.S. imperial engagements in Asia, and their unintended consequences, is thus necessary in order to make affiliations between Iranian and black liberation movements legible within this field. Correspondingly, the history of Iranians in the United States has fallen outside the borders of Asian American and ethnic studies, a legacy of the specific national, ethnic, and racial formations that emerged in the 1960s to challenge racism within the academy. While Iranian foreign students participated in some of the historic movements that contested institutionalized racism on campuses, they did so as allies in a broader anti-imperialist coalition, and not as an ethnic, national, or racial group advancing their own set of demands for inclusion.

4

The absence of Iranians from Afro-Asian studies can also be explained by the fact that the timeline of semi-colonization and decolonization in Iran does not align with the other major sites of affective attachment and political inspiration, such as those in China, Cuba, and Vietnam, around which Afro-Asian solidarity coalesced after World War II. Iran had already experienced the rise and fall of a mass anti-imperialist movement by 1953, two years before the Bandung Conference of African and Asian nations. While this conference looms large in Afro-Asian historiography, it occurred after an historic defeat for Iranian anti-imperialist forces. 5 From 1953, when a CIA-backed coup overthrew the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh and crushed the popular oil nationalization movement, until the 1979 revolution – in other words, during the decades that have figured most prominently in Afro-Asian studies scholarship – Iran was a U.S. client state. However, this did not stop it from sending a representative to Bandung, who made rhetorical denunciations of colonialism on behalf of a dictatorship that was busy turning Iran into a laboratory for U.S. development schemes and U.S.-trained secret police torture tactics. 6

The Iranian case points to the superpower alliances held by many of the third-world nations present at Bandung and to the importance of distinguishing between people-to-people and state-oriented solidarities, which tended to become entangled in articulations of third-world solidarity. As postcolonial and queer feminist scholars have shown, the slippage between the two frequently occurred at the expense of women, minorities, the working class, and the poor when popular, expansive versions of revolutionary anti-imperialism were constricted by the exigencies of new postcolonial states. 7 Indeed, the conference attendees at Bandung expressed their vision of third-world unity in overtly masculinist terms, as bound by “the ties of this brotherhood.” 8 It is just this cohesion between anti-imperialism and patriarchy that came to dominate the revolutionary discourse in Iran in 1979, and that facilitated the Iranian left’s hostility toward an uprising of Iranian women against a host of patriarchal laws. 9 Defense of the anti-imperialist state required national unity and the silencing of internal dissent, i.e., the disqualification of the liberatory vision of those whom the new state consigned to second-class citizenship. Today, the Iranian state rules in the name of those very anti-imperialist values, albeit with an Islamist coloring, that were held to be the sacred unifying call of an entire era of Afro-Asian solidarity movements.

By considering how Motevalli inherits this complicated and contradictory revolutionary legacy, and reconceptualizes the notion of unity among the oppressed, this essay contributes to the project Gayatri Gopinath calls “a queer critique of the Bandung era moment, its promises of liberation and solidarity.” 10 In our contemporary moment, when postcolonial dictatorships and U.S. wars have been largely successful in rolling back popular democratic movements across Iran, Afghanistan, and the Arab world, it has never been more necessary to develop a queer feminist politics of anti-imperialist internationalism that can respond to multiple sources of oppression across disparate geographies.

The Artist and the Diaspora

Motevalli was born in Iran and moved to the United States in 1977 when she was eight years old. Her father was a working-class socialist who opposed the Shah; both of her parents worked as manual laborers in the Los Angeles area and did not strive for assimilation into middle-class American life. Her family’s political orientation and class status alienated them from the predominantly wealthy, pro-Shah population of Iranians who migrated to Los Angeles after the revolution. 11 Motevalli has held a series of working-class jobs throughout her life, living paycheck to paycheck as she makes and shows her visual and performance art. At the same time, she is a political activist who has mobilized around issues such as sex-worker unions, conditions in public schools, and opposition to police brutality. While these organizing efforts have often given her a sense of belonging, she has also experienced forms of exclusion, for example when she found it necessary to advocate for femme equality within queer people of color coalitions. As a queer feminist working-class artist who is diasporic and transnational, Motevalli can be understood as what Gopinath names an “impossible subject,” illegible within normative constructions of citizenship in the Islamic Republic, in the United States, and within the Iranian American diaspora. 12

For Motevalli, non-identitarian affiliations were an everyday part of growing up in working-class Latino neighborhoods in Los Angeles where, as she puts it, “there was basically no one around me that was like me.” 13 This context created opportunities for friendship and community, but also conflict. For example, her most visceral childhood memory of anti-Iranian sentiment occurred in 1980, during the Iran hostage crisis, when she was harassed by other working-class kids of color: “Every day in my school they would call me Khomeini’s daughter and then the next moment they’d call me the Shah’s daughter. They’d tell me to go back home and they’d spit on me. I remember at one point a group of boys pushed me down on the ground. They were holding me down and spitting on me. They were high school kids and I was ten. It was pretty scary.” This memory reveals how distinct histories of racial, colonial, and class oppression can overlap and collide, often creating barriers to multiethnic affinities. In this instance – a group of older boys physically attacking a younger girl – gender and age hierarchies enabled violent ways of asserting inclusion in an imperial national identity. “There was a pecking order,” Motevalli tells me, “and this was an opportunity to go one step up. I think everyone who lives in low-income neighborhoods has those experiences.” Such experiences have prevented her from idealizing notions of solidarity among the oppressed, even as her life and art are grounded in this affective and political project.

During the same period of heightened animosity between the United States and Iran, Motevalli also first encountered the repressive state apparatus. FBI agents followed her home from school, she remembers, and tried to intimidate her into answering questions while her parents were at work. This, she says with a laugh, “didn’t make me love this country.” Instead, she became “very critical of the U.S. government from a very young age.” Later in her life, she attempted to find other Iranians with whom she could connect politically, eventually becoming friends with a group of older leftists who had been active against the Shah. Her differences with them would emerge more sharply upon her return to Iran.

Because Iranian American cultural producers of Motevalli’s generation grew up during a period of intense hostility between the United States and Iran, there has been a recurring tendency to represent Iranian American identity as “caught in between” two nations that are positioned as cultural and political opposites, perhaps unintentionally mirroring the official rhetoric from Washington and Tehran. 14 Motevalli’s response to these polarizing conditions is quite different. Her work refuses to reproduce U.S. and Iranian state discourses that counterpose the two nations. Instead, her artistic and political sensibilities stem from an alternative understanding of difference, one that emerges from woman of color and queer of color critique. Grace Kyungwon Hong and Roderick A. Ferguson articulate these political traditions as the basis for a mode of comparative analysis that “refuses to maintain that objects of comparison are static, unchanging, and empirically observable, and refuses to render illegible the shifting configurations of power that define such objects in the first place.” 15 In this vein, Motevalli’s visual and performance art represents the United States and Iran as heterogeneous, dynamic societies that have long been entangled, and thus exposes the incoherence of the categories on which official and diasporic nationalisms rest. Rather than being caught in between the United States and Iran, Motevalli moves critically back and forth, drawing connections from one site of contestation to another across time and space.

The Occasion and the Exhibit

When she returned to Iran in 2005 following her father’s decision to retire there, Motevalli observed the contradictions of Iranian society up close. Nationalization of land and industry, a crucial postcolonial strategy for reclaiming resources, had become the means by which a small elite connected to the government and military concentrated wealth and power in their own hands. At the same time, unemployment and incarceration of the poor were endemic. Motevalli began “a real questioning of even the notion that leftists were upholding, that nationalization of resources was a good thing.” If the unjust outcomes of postcolonial economic development became clear to her on this first trip back, her next trip in 2009 would deepen her alienation from the Islamic Republic’s anti-imperialist rhetoric.

In 2009, Motevalli arrived in Iran just prior to the June 12 presidential elections. “It was a very exciting time,” she remembers of the final days of public campaigning for opposition candidates Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi. “People were out in the streets and there were debates everywhere. People would literally stop traffic and get out with their parchams [flags] and dance.” This outpouring of national optimism quickly transformed into outrage when the incumbent, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, was speedily declared the victor. In what became known as the “green movement” after the color associated with the opposition, millions of people took to the streets to protest election fraud and to demand that their voting rights be respected. Government and vigilante forces responded with tear gas, guns, and clubs, and shot, beat, and arrested unarmed nonviolent protestors. News of the torture of jailed prisoners leaked out and circulated widely. “I was there for the fallout after,” Motevalli says, “marching and seeing what was happening to people when they were marching.” Witnessing the brutality of the crackdown made her want to counter the Islamic Republic’s leftist sounding propaganda:

I was hearing this anti-imperialist rhetoric, this constant refrain from the government. [Back in Los Angeles,] I was [used to] hearing leftists say Ahmadinejad is so great, I mean look at how he goes up against Bush. I was just really wanting to question these notions of anti-imperialism. In Iran, they [the government] would speak so much of struggles of the oppressed in the U.S. and act as though they were at one with that struggle. I wanted to somehow put that on blast.

Her chance to challenge this synergy between the diasporic leftists’ and the Islamic Republic’s versions of anti-imperialism came with the invitation to mount a solo show at Tehran’s Aaran Gallery.

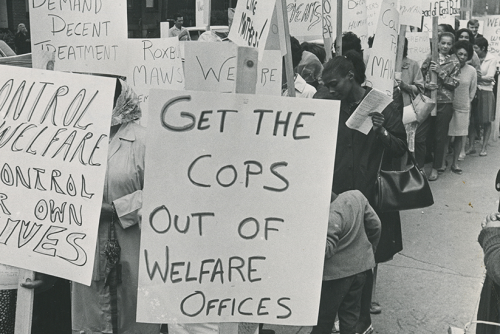

Here/There, Then/Now opened on the one-year anniversary of the contested Iranian presidential elections. It was also the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which, in addition to waging direct action against Jim Crow segregation, organized voter registration campaigns in poor black communities across the U.S. south. Motevalli had studied SNCC, and one of her mentors had been the group’s California chair under H. Rap Brown. Earlier in 2010, she had curated an exhibit of SNCC archives, art, and ephemera. She turned to this material for the Tehran show because, as she puts it, “I understood the importance of the early years [of organizing] and how the violent response to the voter registration drive evolved into the later years of SNCC.” Motevalli wondered if the violent state repression she witnessed the previous year in Iran would radicalize green movement protesters and what that might mean. She also wanted to challenge the Iranian state’s appropriation of “the oppression of Black people historically in the United States” as part of its anti-imperialist propaganda, and hoped her exhibit “could shed some light on the hypocrisy of oppressive power.”

The Aaran Gallery provided an ideal space for Motevalli’s political and aesthetic interventions. Nestled in a kuche (alleyway) in the Karimkhan neighborhood – an old working- and middle-class section of Tehran frequented by intellectuals, artists, activists, and students – the gallery has survived as a vibrant cultural space despite rigid government censorship. This is partly due to its discrete location off the main boulevard, which may make it inaccessible to the uninformed, but which does not necessarily render it the exclusive space of Tehran’s elite. Higher education is free in Iran, and Iranian youth from different classes and neighborhoods are drawn to the few cultural spaces outside government control. Like the green movement itself, which the regime dismissed as the work of a Westernized elite, the Aaran Gallery’s existence reflects widespread alienation across different demographics of Iranian society and the resulting desire to forge communities of dissent. The gallery’s ability to stay open is also a result of the necessary creativity exercised by curators and artists in order to avoid attracting the wrong kind of attention. As Motevalli explains, she knew she “could not directly discuss or critique the prior year’s elections and its aftermath” due to fears of government persecution. “I chose these images [from the SNCC archives] as a metaphor,” she says. “Although the histories and struggles were different, some of the hostile and violent reactions by the state were parallel.”

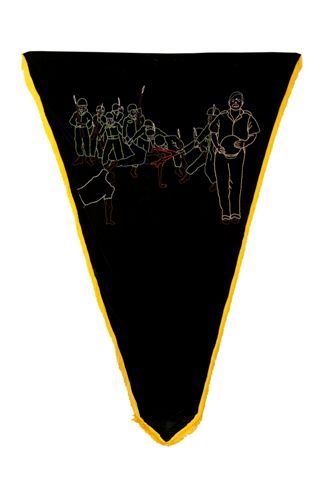

She hoped to illustrate this point indirectly by draping the interior gallery walls with a series of eight-foot-by-four-foot black roseh flags.

On each flag, she stitched reproductions of Danny Lyon’s iconic photographs of SNCC protesters, including scenes of police brutality and of activists giving the Black Power salute.

She chose these images because, she says:

Iranians were in their own bubble and thought that perhaps they were the only ones who had seen this type of oppression. That bubble of not being in direct contact with the world outside of the simulacra of a world created by social media was making people feel hopeless, including my own family members. I wanted young Iranians to see that persistence and perseverance go hand in hand.

Although roseh flags are displayed on Shia holy days, Motevalli “want[ed] to seculariz[e] the flag” by showing “that it’s about struggle and connecting with struggles.” Roseh flags are carried during annual Ashura marches to honor the deaths of Husayn and his companions during a massacre at Karbala in the seventh century. This ritualistic homage to martyrdom was mobilized as part of the revolutionary fervor that overthrew the Shah in 1978–79; at that time, the trope of the underdog Shia persisting in the face of overwhelming injustice was imbued with new anti-imperialist connotations. Since then, annual Ashura marches in the Islamic Republic have been major events orchestrated to support the regime. However, during Ashura in December 2009, many people seized the opportunity of a state-sanctioned public gathering to rally pro-democracy forces. Police opened fire on this sacred procession, making it the bloodiest day of the uprising and the final public protest that brought months of open defiance to a close.

In the embroidered outlines of an unarmed black man pulled and dragged by multiple police officers simply for trying to register to vote, viewers of Here/There, Then/Now might have felt a twinge of the familiar, recalling the eerily similar scenes of violence meted out against unarmed Iranians for defending their voting rights.

The large scale of the reproductions allowed for a face-to-face encounter with images of black resistance rendered with the graphic starkness of colored thread against black velvet.

The necessary selection process involved in transforming photographs into a series of hand-stitched lines on fabric imitates Motevalli’s careful engagement with U.S. civil rights history. Her choices about what to make visible and what to leave open for the viewer to fill with images from other times and places gave aesthetic form to her deliberate crafting of a cross-racial, transnational, and temporally fluid genealogy of resistance.

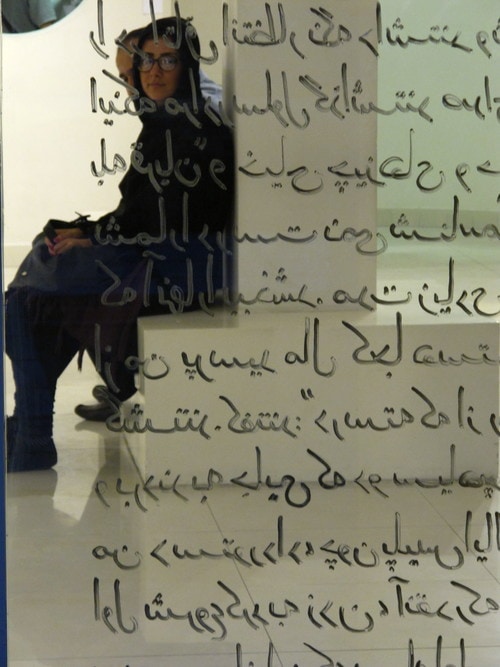

In addition to the roseh flags, Motevalli handwrote the first-known Persian translation of Hamer’s speech at the 1964 Democratic National Convention with black marker across the gallery’s front window.

This speech was Hamer’s testimony as to why she and the other delegates from the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party should be seated as the legitimate representatives from their state instead of the all-white official delegation. Motevalli has had “a love and admiration for Hamer” ever since she learned about her as a teenager. She came to know several people who had worked with Hamer and heard them describe “how even in dire situations she would lift everyone up so they had the vitality to continue.” During a period of severe demoralization and reaction in Iranian society, “writing the speech on the window became a performative act,” Motevalli recalls: “I loved watching people read it and I really hoped that it would inspire people in the way it moved and inspired me.”

Motevalli did not render this speech in calligraphy, the stylized motif that appears in so much Iranian diasporic art, but rather in the less rarified, more intimate handwriting of everyday life. This quotidian aesthetic invoked Hamer’s role as a grassroots community leader whose signature frank speaking style helped to make her an effective mass organizer among the poor. 16 In a quasi-underground space in Tehran, her words ran across the transparent surface, across the viewer’s own reflection, mediating between history and the present, between Iranian and American “freedom dreams.” 17

Motevalli’s desire to connect African American and Iranian opposition movements can be understood as part of a longer genealogy of what I call “Afro-Iranian solidarities” going back to an era of mass movements against racism, colonialism, and war in the 1960s and 1970s. In the aftermath of the 1953 CIA coup in Iran, tens of thousands of Iranians came to study in the United States, and a significant minority became active opponents of the coalition between the Shah’s dictatorship and U.S. empire. Constituted as the Iranian Students Association, Iranian anti-Shah activists in different chapters around the United States worked with SNCC, the Black Panther Party, and various black student unions, and participated in the student strikes against racism at San Francisco State College and the University of California at Berkeley. 18 They saw black revolutionaries in the United States as their allies in a common project of human liberation, and this view manifested in concrete acts of solidarity. For example, leading black radicals, such as Angela Davis, went on record in support of Iranian Students Association campaigns against the political repression of Iranian dissidents by the United States and Iranian governments and the association joined Black Panther rallies to free Huey Newton. 19 Motevalli’s turn to the images and voices of SNCC was thus not as coincidental as it might seem. Her decision as an undergraduate at San Francisco State to study and work with Davis also can be seen as a continuation of these unofficial, diasporic routes of identification and affiliation.

Queering Afro-Asian Solidarity

To inherit the legacy of the Iranian Students Association, and of the internationalist third-world left more broadly, was, for Motevalli, a mandate to reimagine the meaning and practice of solidarity. Her lifetime of negotiating hierarchies and exclusions even among people of color, and her grounding in queer feminist political praxis, enabled her to reject the “brotherhood of nations” model that dominated the Bandung era, with its corresponding view of the world as a contest between anti-imperialist and imperialist states. Instead, Here/There, Then/Now established an alternative framework, one that crossed geographic and temporal boundaries without collapsing or ignoring them. By suggesting that viewers consider the relationship between the embroidered reproductions of SNCC protesters and the Shia symbolism of the roseh flags, and between Hamer’s translated words and the events that had so recently unfolded on the streets of Iranian cities, Motevalli created what Hong and Ferguson call “strange affinities.” 20 These juxtapositions trouble essentializing categories of identification and comparison, and allow affects and emotions to flow in new directions, toward new sites of empathy. In this way, as Hong and Ferguson argue, strange affinities produce new kinds of relational knowledge that would not otherwise be available. 21 As the words and images of a southern African American insurgency from the 1960s resonate with participants in a democratic uprising in Iran in 2010, the binary logics that structure dominant ways of imagining the relationship between the United States and Iran gave way to an alternative logic of commonality: against the overwhelming forces of state violence, there are ongoing struggles for justice that threaten the very foundations of each nation-state, and that lay bare the fatal limitations on democracy and freedom in each place. Motevalli’s transnational artistic practice thus illuminates the basis for an internationalist political sensibility.

Here/There, Then/Now‘s strange affinities also mapped a new genealogy of Afro-Iranian solidarities. By displaying Hamer’s speech as the framing text of her exhibit, Motevalli departed from Cold War iterations of anti-imperialism that tended to maintain the dominant position of men and to relegate issues of gender and sexuality to the sidelines. The speech was not only a defiant act in the face of entrenched white supremacist political power; it was also a brief, at times harrowing, autobiographical account of the intertwined oppressions that shaped Hamer’s life. After telling the convention that she lost her job as a sharecropper on a plantation for attempting to register to vote, she described the lengthy beatings that she and several other black women received in a Winona, Mississippi jail in 1963. Toward the end, she said: “One white man – my dress had worked up high – he walked over and pulled my dress – I pulled my dress down and he pulled my dress back up.” 22 This beating blinded Hamer in her left eye and caused permanent damage to her kidneys. 23

Hamer’s decision to speak publicly about the gendered and sexualized nature of the assault, as she did repeatedly over the years, reflected her deeply personal awareness of how white supremacy relies on violating black women’s bodies. In fact, in the closed-door meetings at the 1964 convention, in which Democratic Party officials and national civil rights leaders maneuvered to undermine the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, she expressed her outrage “with a Democratic Party [that] would even consider seating people who had helped participate in the sterilization of women in Mississippi.” 24 Hamer had herself been subjected to nonconsensual sterilization, a policy that used eugenicist logics to target black women. 25 Her refusal to stay silent about gender and sexual violence was part of her commitment to the overall democratic, anti-racist struggle she helped to lead. It shifted the meaning of concepts such as freedom and liberation beyond simply the exercise of the vote or the right to unsegregated public space. Her outspokenness about the full spectrum of the oppression she faced often relegated her to the margins of the mainstream, middle-class civil rights movement. 26 Through Hamer’s words, Motevalli invoked the gendered and sexualized violence that accompanied state repression of voting rights in Iran, including the rapes of jailed protesters, without alerting the censors and without isolating or exceptionalizing the actions of the Islamic Republic.

Motevalli’s choice of Hamer, rather than a higher-profile male civil rights leader, as a figure of inspiration for Iranians can be understood as an act of queer affiliation with a marginalized genealogy of the black liberation movement, with working-class black women’s victimization, struggle, and leadership. Hamer herself can be understood as a queer subject in relation to the mainstream civil rights narrative of progress and inclusion, where queerness signifies, in Gopinath’s words, “not so much a brave or heroic refusal of the normative … as much as it names the impossibility of normativity for racialized subjects who are marked by histories of violent dispossession.” 27 Although Hamer’s speech at the Democratic National Convention was a detailed account of her personal experience, Motevalli’s queer mapping of Afro-Iranian connections showed that these words could travel across time and place as a searing challenge to the meaning of democracy itself. Hamer ended her speech with a question: “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?” Her bold appeal for recognition and inclusion within the Democratic Party, an appeal that was squarely rejected, ultimately exceeded the terms of reformist civil rights strategies and fundamentally questioned the nationalist ideology of American exceptionalism. Rather than a recourse to an abstract liberal humanism, Hamer’s demand that black people be able “to live as decent human beings in America” carried revolutionary implications, naming precisely that which a system based upon on assaulting and exploiting black humanity has still been unable to deliver.

In the aftermath of the 2009 elections in Iran, millions of people learned a similar lesson as those delegates in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party: the more sincerely they sought to make democratic claims on the state, the more viciously they were repressed. In a country in which the word “revolution” has become a staple of the state’s self-legitimizing propaganda, the limits of reform left many Iranians demoralized but also posed the same question Hamer dared to ask: what, then, would it take to be able to “live as decent human beings” in Iran? What forms of postcolonial self-determination can be imagined that do not rely on the exclusionary categories of nationalism, ethnicity, and religion, and what new iterations of anti-imperialist solidarity would be required from those Americans who are still working for their own liberation?

Conclusion

By asking members of the Iranian public to read Hamer’s words in the context of their own recent experiences, Motevalli’s exhibit countered the Orientalist logic that structures much of mainstream Iranian American cultural production. Here/There, Then/Now displaced white, middle-class heteronormativity as the reference point for Western notions of freedom and, instead, reoriented viewers toward SNCC activists marginalized by their race, class, sexuality, and gender as the representatives of American democratic aspirations. Motevalli’s queer kinship with Hamer, and the movement of which she was a part, undermined the political substance of attacks on Iranian pro-democracy protesters as “Westernized” – the same insult that was used against revolutionary women in 1979 who rose up to fight for a different vision of a post-Shah Iran. By suggesting that Western influence might come from the voices and histories of those who have exposed the white supremacy, gendered, sexual, and economic inequality that structures “the West,” its power and its global reach, this exhibit rebutted such slanders and reclaimed the black liberation movement as a source of inspiration for Iranians struggling against dictatorship.

If the Iranian diaspora were to be considered within the scope of the fields of Asian American studies and ethnic studies, such claims would help to frame whole new areas of inquiry centered around the links between histories of U.S.-sponsored state violence in Iran, migration and racialization of Iranians in the United States, forms of state violence and racialization of other minority groups within the United States, and various opposition movements. America’s unofficial Middle East empire would have to be integrated into the historiography of Asians in America, propelling a shift to imperial, rather than nationally bounded, analytics for the study of minority subjectivity, politics, and culture. 28 By making art that draws on her experience of flight from a U.S.-allied police state, and her subsequent affiliation with other nonwhite working class immigrants in Los Angeles, Motevalli’s ongoing work helps make salient overlapping affective and material ties that are not currently legible within Asian American and ethnic studies categories of knowledge production.

Most significantly for Afro-Asian studies, Motevalli’s 2010 exhibit in Tehran opened new transnational routes along which the lived experiences of racialized diasporic women could travel. It departed from the norms of third-world internationalism during the Cold War by foregrounding the necessity of responding to multiple forms of oppression without subordinating one to the other, and without subsuming more capacious notions of freedom into support for strong nation-states. Here/There, Then/Now crafted a new conceptual basis for solidarity between the Iranian and African American freedom movements – then and now – that was intersectional and subversive in its multi-faceted critique of oppressor and oppressed nationalisms. In this way, the exhibit juxtaposed vastly differing contexts of repression and resistance and dared to insist that there is indeed a connection, one we must grapple with in order to recuperate the revolutionary demand for structural change and human liberation across the imperial divide.

- The title of this essay invokes Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books to emphasize stark political differences within Iranian diasporic cultural production. While Nafisi offers heteronormative representatives of liberal enlightenment values, such as Anglo-American canonical novels, as the presumed pedagogical tools of freedom for Iranian women, Motevalli’s work draws inspiration from those racialized and gendered subjects within the West who have been excluded from full participation in its democratic promises. For a sharp critique of Nafisi’s book, see Jodi Melamed, “Reading Tehran in Lolita: Making Racialized and Gendered Difference Work for Neoliberal Multiculturalism” in Strange Affinities: The Gender and Sexual Politics of Comparative Racialization, ed. Grace Kyungwon Hong and Roderick A. Ferguson (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 76–109. I am grateful to Grace K. Hong and Gayatri Gopinath for their insightful feedback on an earlier version of this essay.[↑]

- See Manijeh Nasrabadi and Afshin Matin-asgari, “The Iranian Student Movement and the Making of Global 1968,” in Martin Klimke et al., eds., The Routledge Handbook of the Global Sixties (New York: Routledge, 2018), 443–56. Brief mentions of this joint organizing can also be found in Vijay Prashad, Everybody Was Kung-Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001), 137; and in Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin. Jr., Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 135.[↑]

- See Sunaina Maira and Magid Shihade, “Meeting Asian/Arab American Studies: Thinking Race, Empire, and Zionism in the US,” Journal of Asian American Studies 9, 2 (2006): 117–40.[↑]

- Nasrabadi and Matin-asgari, “Iranian Student Movement,” 451–4.[↑]

- See, e.g., Fred Ho and Bill V. Mullen, eds., “Introduction,” in Afro Asia: Revolutionary Political and Cultural Connections between African Americans and Asian Americans (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008); Andrew F. Jones and Nikhil Pal Singh, eds., “The Afro-Asian Century,” Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 11, 1 (Spring 2003).[↑]

- Iran’s representative was Mehdi Vakil, who the Shah would later appoint ambassador to the United Nations. For excerpts from Vakil’s speeches on decolonization, see Vrushali Patil, Negotiating Decolonization in the United Nations: Politics of Space, Identity and International Community (New York: Routledge, 2008), 51, 119–20.[↑]

- See, e.g., Jacqui M. Alexander, “Not Just (Any) Body Can Be a Citizen: The Politics of Law, Sexuality and Postcoloniality in Trinidad and Tobago and the Bahamas,” Feminist Review 48, 1 (1994): 5–23.[↑]

- Lebanese Delegation to Bandung, qtd. in Patil, Negotiating Decolonization, 52.[↑]

- See Minoo Moallem, Between Warrior Brother and Veiled Sister: Islamic Fundamentalism and the Politics of Patriarchy in Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).[↑]

- Gayatri Gopinath, “Affect, Archive, and the Everyday: Queer Diasporic Re-visions,” in Political Emotions: New Agendas in Communication, ed. Janet Staiger et al. (New York: Routledge, 2010), 168.[↑]

- See Hamid Naficy, The Making of Exile Cultures: Iranian Television in Los Angeles (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993); Georges Sabagh, “Are the Characteristics of Exiles Different from Immigrants? The Case of Iranians in Los Angeles,” Sociology and Social Research 71, 2 (1987).[↑]

- Gayatri Gopinath, Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 186.[↑]

- All quotations from Amitis Motevalli are from interviews with the author. I interviewed Motevalli in Los Angeles on November 7, 2014. She also answered additional questions via email correspondence in January and September 2015.[↑]

- See my article, “In Search of Iran: Resistant Melancholia in Iranian American Memoirs of Return,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 31, 2 (2011), 487–97.[↑]

- Grace Hong and Roderick Ferguson, “Introduction,” in Hong and Ferguson, Strange Affinities, 9.[↑]

- Chana Kai Lee, For Freedom’s Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 43. [↑]

- See Robin D.G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002).[↑]

- This research is included in my forthcoming book, Neither Washington, nor Tehran: Iranian Internationalism in the United States (Durham: Duke University Press, forthcoming).[↑]

- bid.; Bloom and Martin, Black against Empire, 135.[↑]

- Hong and Ferguson, “Introduction,” 18.[↑]

- Ibid., 18–19.[↑]

- See Fannie Lou Hamer, “Speech to the Democratic National Convention,” August 22, 1964, Atlantic City, New Jersey, http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/fannielouhamercredentialscommittee.htm.[↑]

- Lee, For Freedom’s Sake, 53.[↑]

- Ibid., 91. [↑]

- Ibid., 21.[↑]

- Ibid., xi.[↑]

- Gopinath, “Archive, Affect, and the Everyday,” 167.[↑]

- Maira and Shihade, “Meeting Asian/Arab American Studies.”[↑]