Introduction

I met Valois Mickens and Zishan Ugurlu when I joined the tour of La MaMa’s Great Jones Repertory Company in 1997. We were on our way to Seoul, Korea for a month-long tour of The Trojan Women, an experimental operatic adaptation of the original Euripides play conceived and directed by Andrei Serban and composed by Elizabeth Swados. Actors speak in ancient Greek, Latin, and invented tongues, and the production uses immersive, spectacular staging to reach audiences beyond the realm of language. The play was first performed at La MaMa, the experimental theater in New York City, in 1974. It has seen a number of revivals in the decades since its first production. I was brought into the company in 1997 because Zishan couldn’t do the entire run of the tour and Ellen Stewart, mama of La MaMa, invited me to share the part. We were Helen of Troy. I was twenty-seven then, Zishan was thirty-six, and Valois, a founding member of the Company, which had formed in the early 1970s, and had played the original Cassandra, doomed prophetess, was fifty-three. (Incidentally, fifty-three is my age at the time of this publication.) Since joining the company, I have toured to Korea, Japan, Italy, Austria, Greece, Croatia, Slovenia, Portugal, and Germany with one or both of these women.

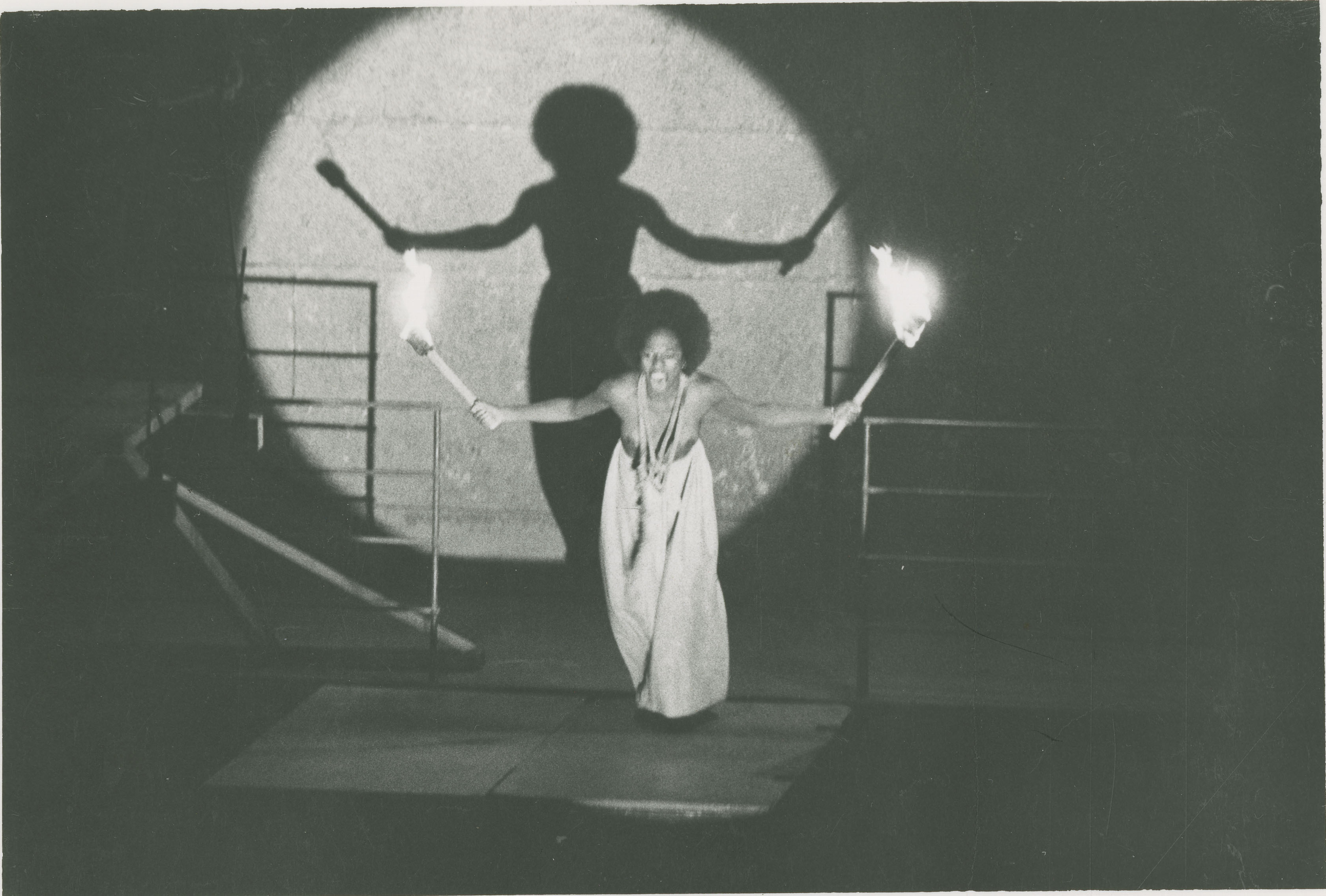

In December 2019, the production was remounted in New York City with an international cast of artists from Cambodia, Guatemala, and Kosovo. Twenty-two years and two children later, I was now in Zishan’s shoes, sharing Helen with two women half my age. Valois was now playing Hecuba, the old queen. Her original part, Cassandra, had been staged to appear bare breasted, carrying lit torches before a frenzied call and response dance with the rest of the women that ends with her woefully carried away by Greek soldiers. Helen is dragged onto the stage with a destroyed dress and rope around her neck. She is pushed into a cart, stripped naked, covered in mud, and raped by a man in a bear head during a savage celebration by Trojans and Greeks alike. They parade her around before beheading her. About this particular iteration of the performance, my peers told me I was brave.

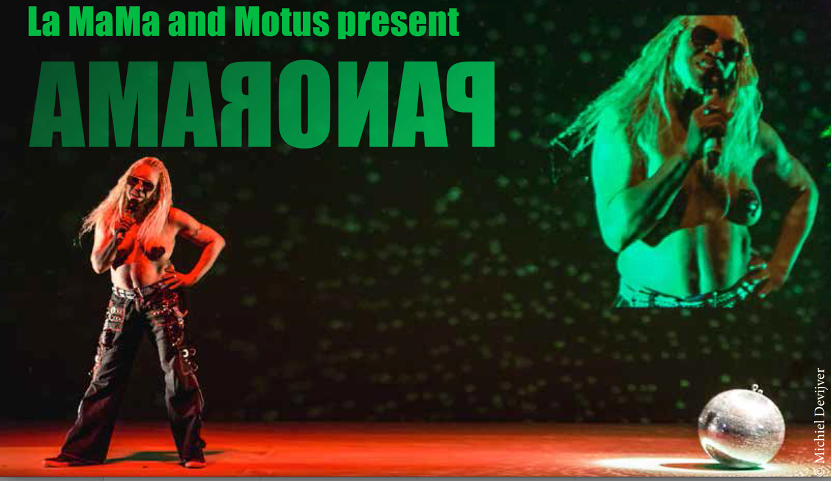

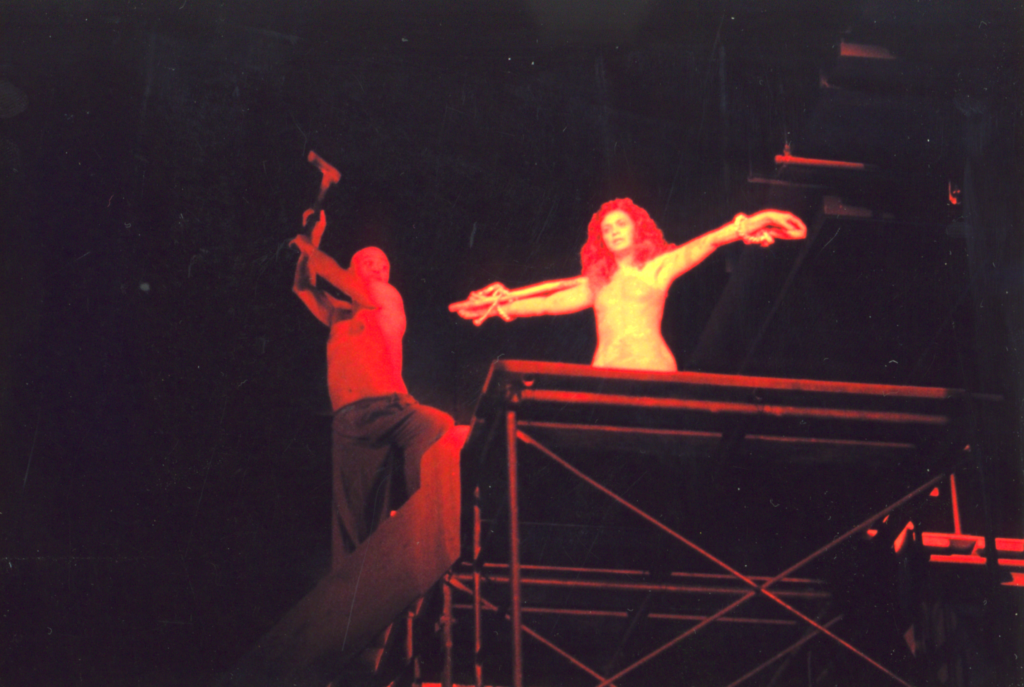

There were many other “brave” shows. From 2015-2017, Valois and I were also in the Great Jones Repertory production of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Pylade, directed by Croatian provocateur Ivica Buljan. In New York City, Italy, Portugal, Austria, Croatia, and Slovenia, once again, Valois bared her breasts and I got completely naked, but in that production audiences spent a lot more time consuming full frontal male nudity under what could be argued was a gay male gaze. From 2018-2019, Valois, Zishan, and I performed in Panorama, a play based on the autobiographies of six members of our cast and directed by the Italian team Motus. Now seventy-two, Valois wore pasties, Zishan at fifty-five bared her breasts with the word “terrorist” written across them, and I, forty-six, disrobed for Valois to draw my portrait, joking that getting paid to strip in Times Square made sense since I’d already been naked all over town in the name of art; why not get paid for a change? We performed somewhere between forty and fifty shows in New York City and across Europe. Between the three of us, we’ve accumulated close to 100 years baring our bodies in the name of a meaningful encounter with mythological archetypes and simple humanisms.

In my academic work, I have drawn on and sent others to read Rebecca Schneider’s vital book The Explicit Body in Performance (1997) to engage with the labor of my naked body in La MaMa shows and my own work. In my own work, I have often used my naked body to interrogate intersecting legacies, including the one tied to what Schneider calls “commodity dreamscapes.”1 I also weave Audre Lorde’s Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power into my work, recognizing how our naked, explicit bodies allow us simultaneously to wrestle with commodification and our own needs in order to, in Lorde’s words, mine “a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane,2 firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling.”3

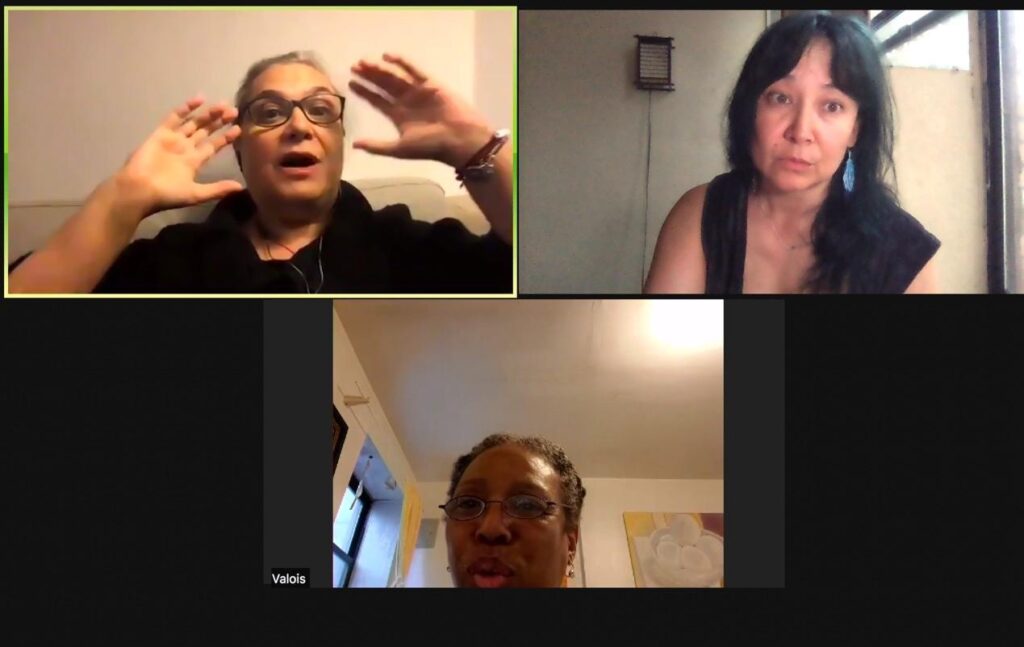

In 2021, I sat down with Zishan and Valois to talk about these issues. I did not try to force the conversation into the realm of academia, even though Zishan and I were presently examining the feminine wrath within the archetype of Medea for an upcoming production that she is directing, and we can all thrum in the delicious heat of theory. Instead, in the conversation that follows, I simply wished to check in with my beloved sisters, to track how each has fared in the march of years, and, one year into a pandemic that changed everything, to reflect on how we were experiencing our bodies and the possibility of public performance.

Between our eastern time zone and Zishan’s later hour in Turkey, where she was living for most of the pandemic with her mother, we managed to grab a moment to talk. What I took away from our conversation was that regardless of how progressive, political, women’s college-educated or tenured professor, head of program, survivor, elder, super star we were, each of us was still in need of some radical self-loving.4 Our three-way conversation does not pull the problem out from its root source, but it does elucidate the ways that capitalism, ableism, white supremacy, hetero-patriarchy, and ageism are calmly maintaining their hold on those of us who really do know better but struggle to feel the radical truth of our beauty on this planet.

Interview

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for clarity.

June 2021

maura: Thank you both! Okay, we’re recording now. So, as I mentioned, I figured I should talk to these two women who have been naked on stage with me for decades. But this isn’t only about being naked. This is about our bodies. Our bodies have been seen in many countries in all sorts of forms. Zishan, you talk about this in Panorama. I could find your lines from the script, but do you want to tell the story?

Zishan: Sure. My first movie I auditioned for, I got the part. At the end of the audition, they asked if I wanted to be naked. I was like, “Fully naked?” They said, “Yes, full frontal.” In a Muslim country. It’s very unusual. Do you know what I mean? If I was not already in La MaMa, it would not have been so easy to say yes. But I said, “Let me think about it,” and asked my parents. So my mom was immediately like, “How can you do that? It’s not a good thing.” But my father said, “What do you want as an artist? Why is it necessary? Is it necessary? What is the role? And is it okay?” So I said, “It’s in the shower.” He said, “Well, okay, you cannot be in the shower not naked, right?”

I was the first fully naked woman in an artistic movie filmed in Turkey. Opening night, we were sitting there, and when we watched the scene, the whole theater gasped and I slid down in my chair. But my father, who was sitting behind me, said, “Sit up!” So I did. I just did. This is a great story for a Muslim country. A woman is naked and then the father in this patriarchal country is supporting her. It was incredible. And after that, I was in Trojan Women. I was naked as Helen. I have to say, the body is not easy to expose, but I think La MaMa gave us the courage to be free and brave as women. To make choices. That is untraditional. That is liberating. That is revolutionary. I think that’s what I would say.

maura: That’s so beautiful. And just thinking about how Rob [Laqui] was just joking [during a company meeting just before our interview], “Is it naked-naked or La MaMa-naked?” Rob’s joke was that La MaMa naked is actually emotionally naked and in a gold thong and gold sneakers or something. But, you know, you and I were actually naked, like, butt-ass naked. The boys always got the gold dance belt if Ellen was around.

So, I want to go from the beginning and then jump into the future. Valois, I can’t remember exactly, but your story about Cassandra includes Andrei saying that you’ve got to do it right now or you’re not in, right?

Valois: Yes. I wasn’t ready to get up on my feet because we’d been sitting in a circle, you know, rehearsing the show vocally, and it was time to get up on our feet and I wasn’t ready. So I just improvised. I just got up because he said, “If you don’t do it, somebody else will.” So I got up and I did it. So there you go.

maura: So Zishan and I both came in as the mid generation, once the work was established repertory. But for you, originating it in the seventies, that is so different. Even you and I doing it again just before COVID, I feel like the conversations around gender, around representation, conversations around sexual assault, violence against women, they’ve evolved. For me, that created a different context. But when I think about creating this in the seventies in the midst of all the so-called liberation that was happening in America and American theater, how did it come to be that Cassandra was running around with her breasts bared, carrying fiery torches?

Valois: Andrei just told me that’s what was going to happen. You’re going to do it topless. And I said okay because I had done modeling for arts classes in schools. So I didn’t have any problems with nudity. You know, the only time I had a problem with it was the first day I got up on the stand to pose in front of a class and it went away in five minutes. It’s no big deal. So when Andrei asked me to, you know, he didn’t ask me, he told me: Cassandra was going to be topless. I didn’t ask why. I just had to figure it out for myself.

maura: So it wasn’t an outgrowth of the company’s experiments or anything like that. It was just one of those situations where your director’s just telling you—

Zishan: I’m sorry, I have a question about this. Did Andrei only talk to you about like, Oh, you’re going to play this role, make it? Or did he talk to you about everything, you know, because nakedness was not an issue at that time? The nakedness in the seventies was not something like that. The director tells you to be naked, you know, you’re going to be naked.

maura: Right. The context of Open Theater, the Living Theater, all of this was happening in the streets, and art was protest, and, correct me if I’m wrong, but also, like with the part of the ghost of Achilles, you were seeing male bodies in that way too. Whereas in this last version, that disappeared. The female bodies were allowed to stay on display and the male bodies were protected.

Zishan: I didn’t know that. Is it true?

maura: It really feels that way. I don’t know. Well, you know, in the process, in this most recent process, because everything was triple cast or being cast even during the run, it seemed like we saw almost every woman’s breasts in that process of auditioning and rehearsing the part of Cassandra. And then I’m hearing that the woman from Kosovo who was to be the international cast option for Helen, had never been naked on stage and I felt like I was being enlisted to coax her into it, which was a complex space to hold. I remember me and Mattie, the next gen Helen, explaining that she didn’t have to shave. I mean talk about cultural exchange!

So anyway, I felt like I’d just seen an army of breasts in the process and then, suddenly, Andrei says, “We don’t need it. Cassandra is actually going to be covered now.” But after we’ve actually seen all these women! I mean, it was a coercive environment and I’m still reckoning, as someone who loves to be pushed to new limits, with what we all consented to do. We enacted the destructive power dynamic of the play within the process. Women’s bodies were so disposable. I mean, the men were more clothed than ever before.

Valois: I remember we were performing—I think it was in Iran—and I had to be covered. I had to wear my blouse because a woman can’t be shown topless there.

Zishan: Did you guys do Helen then?

Valois: I’m trying to remember. I think she might’ve been covered too. I don’t think there was any nudity in Iran.

Zishan: I think these tensions are important. You know what I mean?

Valois: Cassandra was supposedly a mad woman. She’s running through the streets with fire, telling everybody… And women, when they are mad, they rip their…

maura: Yeah, I mean, dramaturgically, I get the image of rending garments. It’s supposed to show grief, rage, and extreme emotion. I mean this is one of those conversations we’ve had so many times in this household, right? We don’t have an issue with nudity. It’s always just a question about where the power is in this conversation and what is the context. Like when we did Pylade with Ivica. Marko Mandic does half of the show naked, going about all of his tasks. So, I recognize that it’s a queer director, it’s a queer aesthetic we’re able to live in because there’s an absence of cis-hetero male protection. Well, mostly. Some of the guys never took their pants off.

Valois: Well, I’ve often wondered about his nudity because, you know, a lot of people thought he was crazy. I mean, people actually thought that Marko was nuts, but he was doing a role. This was what he was supposed to do. He’s an actor for God’s sake, and he did it very well.

Zishan: Marko is a European actor. So when you go to Germany, everyone is naked. Musicians are naked. The nakedness is not a question of being naked. America is an extremely, extremely conservative country on so many levels.

Valois: The country is descended from those Puritans that came here.

maura: In terms of our bodies, onstage and onscreen, we’re long time veterans. We’ve done this for decades. How has your relationship with your body changed with age?

Valois: When we did Panorama, I was very self-conscious about my stomach. I couldn’t do my dance the way I wanted to because I was afraid to turn sideways, you know? ‘Cause you could see my belly hanging over my pants. I mean, I tried, but there was nothing that I could do about it.

maura: Well, I think it’s a natural process, but we think it’s a problem. That’s the thing.

Valois: I guess I’m a perfectionist in that way, you know, wanting to have the stomach gone.

maura: I mean, I’m just going to say, at fifty, okay, over fifty now, and approaching menopause… I get it, the belly thing is a thing, but I just keep asking myself, Can you build a healthy relationship?

Valois: And now I don’t like wearing a bra because I can’t breathe with them with the asthma and everything. So now I’m self-conscious about nipples showing through my clothes. But when I was younger, I didn’t care. Now, it’s different, and so I just take paper and tape so there’s no imprint or anything.

maura: So Valois, you felt that way about your body, but you still did it. You still came out and danced with pasties on. You still did the thing! I look back at old photos and there is this conversation I keep having with myself: Do you remember how much you hated your body then? You hated your body then and you hated your body then and you hated your body then. So, are you grown up yet? Have you learned anything yet? Can you love yourself now because you didn’t love yourself then and you thought your quads were too big for ballet at sixteen years old, you were too thick as a dancer when you twenty-five, too big for an Asian every time you went back to Vietnam and they couldn’t cut arm holes to fit your biceps. And I’m looking at myself thinking I can’t believe I wore something that was that small ever, right? I just remember all of the self-loathing. But, as a performer, I was like, I feel bad about my body, so fuck you. I’m going to show it to you because I am so angry about the shame that I’ve been made to feel about it.

That doesn’t mean that I ever escaped it.

So I just wonder in that moment where you decided, well, I’m doing it anyway, did you think, I do this out of defiance because I feel bad? Or did you think, This is what the show needs?

Valois: Yeah. I thought, I’ve got to do this. And the audience will see an older woman’s body, and that is what it is, you know? And an older woman can still do a sexy dance. That’s where I went with it. I tried to anyway. But I had all these conflicts in my head.

maura: Well, it created an amazing photo and it gets so much play ‘cause it’s hot and it’s so raw, you know? I just want to say thank you because as somebody who is a little bit further down the line you really changed my perception. I think it’s really cool.

Zishan: But I think—one thing that it’s interesting to me, Maura, is that you said in your twenties you were thinking your body was not good enough. Not good enough. This is interesting, right? Because we have been taught to hate our bodies. Because for a woman, the body is objectified so much. It is touchable. It is breakable. It is do-whatever-you-want. Rape it. Fuck it. So, I mean, specifically in my country, because I grew up in Turkey until the age of thirty, it’s a long time where you are oppressed. It’s all already in my DNA. But the one thing that I have to say is that because of this resistance to the oppressive country, when an opportunity comes, I am thinking, Fuck you, I am just going to do it.

So when something happens like Panorama or Trojan Women, you look at the show and you say, Oh, the show needs it. It’s not about sexiness. It is not about, like, nakedness. It is, Oh, this Helen of course will be humiliated, will be raped with all that mud and hay and everything. Of course we’ll be naked. It’s more vulnerable, more shocking. And it’s needed.

When I went into Panorama, I was thinking, What are the interesting choices? And when I opened my bra and my shirt I was thinking, God, I am fat. Or before, my boobs were never big enough. You know? And now I am writing “terrorist” on them. And, it takes time to do that. It’s durational to write something. People are looking at you and they are judging you. They say, Oh, you’re fat.

en/panorama/

Valois: It feels like that. And maybe they are like that, but I think they don’t see it that way. It’s a very powerful moment. They don’t look at it that way.

Zishan: Exactly. I know that. I know because the reason I am doing it is clear. Even if I sometimes think, as Maura said, It’s not good enough. It’s not perky. It’s not whatever. But even when you are thinking that way, because we are artists and this is what has to be seen, it must be done. You’re saying to yourself as an artist that it’s okay. My body is sacrificed in this way because the show needs that moment because it’s a powerful moment.

And you can see aging women. It is brave enough as an artist to make an interesting choice even more powerful and much bigger. Yeah. Because you’re not thinking, Am I sexy enough? Because this is not about sexy enough. It’s not about being hot. It’s about the moment that needs this thing. And for you, it’s a task. And it is an artistic choice. So that’s what I am thinking.

But it is not easy. I have to say, if I was younger, you know, like, playing Helen in 1997, it was much easier to be naked. And during the feedback, it was okay to be naked and stand there. I didn’t want to cover myself. But it is getting more difficult with my body because of the aging body. But I’m still saying if it is necessary as an artistic choice, I will do that with all the vulnerability of the aging body to be seen. I will do it because aging bodies are so difficult to see onstage or onscreen. I think it is the most wonderful thing to see a woman who is older and is acting and still alive, still passionate.

It’s just, fuck you, all the moments. You know what I mean? Fuck you, patriarchy. Fuck you. This is a woman who is seventy-something years old and dancing, acting, talking, telling the story. And this is theater. Because you don’t see that in real life. To me this is incredible.

maura: Yeah. That’s so beautiful and so true. So I’m wondering after the defiance… How are you kind to your body these days? Yes, with the pandemic, we’ve often been alone with ourselves or with our bodies, and then there’s the pandemic body that gets joked about. One of the practices I try—and I thank my therapist, Cassie, for leading me to this—is… Well, ok, when I get mad, I get mad at my belly. I yell at it. So the practice is to remember, gently, Don’t yell at your cells, at your selves. You wouldn’t talk to your child like that, would you?

Valois: I just worry about the health of my body because, I mean, I’m doing all the things on the outside. I mean, with my skin, my lotions and all that, but I’m not dancing, and that’s not being kind to my body. But I’m afraid of the pain. There’s pain after not doing something for a long time. Do I want to do that to my body? Do I go through the pain to get it to look the way I want it to look or just let it be? But then if I let it be, that also hurts my health. So it’s a conundrum, you know? It’s hard.

maura: You know, you’ve just opened a whole other thing about pain. That’s another conversation we can have, just about how much pain becomes part of the conversation. Discomfort and pain and management. It’s a lot. It’s not just the appearance of our aging body that is seen because it’s onstage or onscreen, but the body that we are managing and the physical pain is definitely–

Valois: –part of that.

Zishan: I was thinking that with the pandemic there are two things that are clashing with each other. But ironically it’s comforting. One is that I am kind to my body in a sense because I am in a container, because I’m not going out, because of so many reasons, online teaching, and the way we are living in a pandemic. I am not rushing anymore. This makes me so happy that I cannot tell you because I realize my life in New York—you get up, you get out of the building, you go to school, you teach, you teach, and now you get out of the school, and you go to rehearsal. Then rushing right out of rehearsal, you come home and either you eat or you don’t eat. Do you know what I mean? We are not aware of how New York is actually driven by the validation. So I realized, more and more, that I am not able to rush, not able to go to the subway, not able to be running late for this, running late for that. It gave me a way of grounding. I feel grounded, but at the same time, I feel so grounded that, as Valois said, there is no exercise. There is no moving around. I don’t go and walk or go to the gym. My body is feeling a craving that reminds me that I am a walking creature.

So on the one hand, not rushing is making me happy, but at the same time, not being able to walk, not being able to go out… It is kindness and not-kindness. I should be doing gentle exercises. Like a gentle dance is the best thing because it reminds you that you have a body and you don’t have to have a word.

Valois: Yeah. I remember the days when I had the space, when I was living in Brooklyn, in a loft, I had the space to move, and I would just put the music on and just groove. I would dance for like three hours straight and not know it, you know? And it felt good. It felt really good.

maura: That thing of a bit of gentle movement. I came out of COVID remote teaching with a diagnosis of arthritis in both of my knees. I wasn’t doing anything but sitting at this damn computer because I was teaching non-dancing dance courses like composition. Even if I tried to stand for the whole class, it was still settling in. Somewhere in the winter I realized, “Wow, both of my knees are killing me.”

Valois: I’m glad I live on the top floor because that’s the only exercise I get. Carrying heavy carts of food and stuff, you know? It’s like weight training, pulling, you know? So I call that exercise, but it’s a strain on the body because I’m not doing enough, you know?

maura: Do you mind saying when your birthdays are, how old you are?

Valois: We just celebrated my mother’s birthday a couple of weeks ago. She was a hundred years old. Yeah. I made a video of her with her walker with a band we hired to play happy birthday in a jazz way. And she was moving and, you know, she was a dancer, too, you know, and I saw her leg go out like—like that. Yeah. She’s still dancing.

I’m seventy-six. April 5th, 1945. So I’m feeling it now, the past two years. It’s the first time I’m feeling my age because I’m not moving. I’m not doing what I should do to keep myself together. You know? Yeah, you can’t let yourself fall apart. That’s what my mother said: You have to eat right and keep moving. And she was right. Have to keep moving.

Zishan: She’s right. I’m sixty now.

maura: Wow. Congratulations. I turned fifty last year and I felt like, wow, I accomplished something. I’m still here.

Valois: You look thirty-five.

maura: But that’s one of those funny things. I have experiential knowledge of living through things but people think I’m younger so they treat me like I’m younger. And so they have lower expectations. And then they think I’m smarter than I am because they think I’ve just been around a little bit. It goes both ways for women, the ageism.

Well, wow, thank you both. I hope I get to see you in person in August and I hope we will eat and travel together again soon. I love you.

Conclusion

It’s been a long couple of years since that conversation. As mentioned in my introduction, Zishan is workshopping a reboot of Medea, the Great Jones Repertory’s very first production. In the two years since, we have made a variety of works for live, and digitally mediated realms. At New York Live Arts in 2022, I stripped down for a “zero-fucks stage presence that only comes with age”5 performance as “The Butch” across town in the unapologetically queer gaze of Vanessa Anspaugh’s choreography. As the years and performances have passed, the questions and provocations raised in our conversation continue to reverberate through our work, as does the explicit fuck-you ambivalence about being naked on stage, and a rebuke at society’s attempts to, as Audre Lorde writes, suppress “the erotic as a considered source of power and information within our lives.”6

Now I ask myself how best to mobilize the erotic as “the nurturer or nursemaid of all our deepest knowledge,” borrowing from Lorde.7 That our bodies are on display and continue to be on display past the peak of commodified desirability challenges the way the erotic has been conflated with the pornographic through the cis-hetero male gaze. In actuality, it is the fullness of the feelings that arrive in us, as performers, in their most saturated potency during live performance that a powerful, pleasurable tension is at play. In our conversation, we discussed sliding in and out of the multi-valenced realms of desire and aversion, the variety of agencies we can claim as performers in exposed and aging cis-female bodies, and how this has varied across our decades of experience. We love performing. In performance lives our erotic drive. We are in pursuit of the high that is fed by a feeling of high-risk. We thrive on the edge of that ambivalence. “For the erotic is not a question only of what we do; it is a question of how acutely and fully we can feel in the doing,” Lorde writes.8 In the undercurrent of our conversation lurks a naked body on stage. She is raising the stakes. She is skating on a sharp blade across all efforts to contain us.

WORKS CITED

Brown, Adrienne Marie. Pleasure Activism. Chico, California: AK Press, 2019.

Cote, Theo. Maura Donohue and Valois Mickens in Pylade. Photograph. 2015. Digital file. Courtesy of The La MaMa Archives/Ellen Stewart Private Collection.

Cote, Theo. Maura Donohue as Helen in Trojan Women. Photograph. 2019. Digital file. Courtesy of the photographer.

Devijver, Michiel. Valois Mickens in Panorama. Photograph. 2018. Digital File.

Lorde, Audre. “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic As Power.” In Sister Outsider. Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1984.

Schneider, Rebecca. The Explicit Body in Performance. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Sun, Joung. Zishan Urgulu in Panorama. Photograph. 2018. Digital File.

Taylor, Sonya Renee. The Body is Not an Apology. New York: Penguin, 2018.

Weiss, Noa. “Hope after Tragedy: Vanessa Anspaugh’s mourning after mornings offers a sprawl of unruly movement and intergenerational tenderness at New York Live Arts.” The Brooklyn Rail, December 2022-January 2023. https://brooklynrail.org/2022/12/dance/Hope-after-Tragedy.

- Rebecca Schneider, The Explicit Body in Performance (Routledge, 1997), 6. [↩]

- For me, a “deeply female and spiritual plane” refers not exclusively to cis-female assignment/agreement. Although I do identify as non-conforming, I spent most of my life and am read as essentially femme. This is a complicated assignment and reading entangled with the ways my naked form’s anatomy is named and consumed within a world dominated by cis-hetero patriarchy of white supremacist power structures. [↩]

- Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” in Sister, Outsider (Crossing Press, 1984), 53. [↩]

- Here I am calling upon adrienne maree brown’s Pleasure Activism (2019) and Sonya Renee Taylor’s The Body is not an Apology (2018) in the wake of this need. [↩]

- Noa Weiss, “Hope after Tragedy: Vanessa Anspaugh’s mourning after mornings offers a sprawl of unruly movement and intergenerational tenderness at New York Live Arts,” The Brooklyn Rail, December 2022-January 2023, https://brooklynrail.org/2022/12/dance/Hope-after-Tragedy. [↩]

- Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic,” 53. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid., 54. [↩]