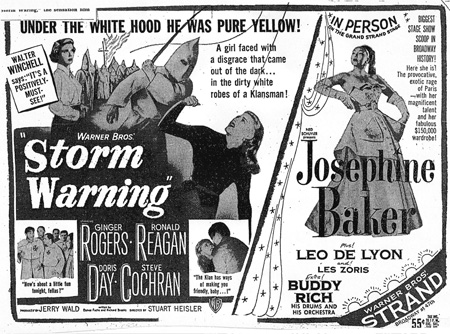

In 1951, Baker commenced her American tour, tied to her civil rights advocacy and her utopian project of the “rainbow tribe.” The force of her agency in its relation to the traumatic Real can be glimpsed in the New York Amsterdam News‘s somewhat uncanny advertisement for her Broadway stage show at the Strand Theater, performed between viewings of the Hollywood film Storm Warning featuring Ginger Rogers, Doris Day, and Ronald Reagan. Briefly, Storm Warning is a 1951 B-movie that recounts the visit of an urban career woman (Ginger Rogers), to her pregnant sister (Doris Day) living in a provincial American town lorded over by the Ku Klux Klan. By chance, Rogers witnesses a Klan murder of a white investigative reporter and is in turn persecuted by the Klan and then rescued by the district attorney, played by Ronald Reagan. In the film’s climax, Doris Day’s character is accidentally shot and killed by her Klansman husband, who had perpetrated the murder Rogers had witnessed.

Following on Baker’s successful desegregation efforts at the Copa City nightclub in Miami, the Amsterdam News observed that “the pairing of Miss Baker with the Strand’s new stirring screen story of the Ku Klux Klan, Storm Warning, was an indirect tribute to the artist,” a tribute that the paper linked to her service as a secret agent for the French Resistance during the war. 1 Significantly, in the ad [Figure 2], Baker as cosmopolitan performer—as a symbol of the “provocative and exotic rage of Paris”—does not just bear the look of high fashion. Equally important, the self-possession of her stance reaches beyond the spectacle of entertainment, leading the viewer’s gaze to the scene of trauma perpetrated by a gang of Klansmen on a white woman, and projects an agency that sharply offsets Doris Day’s helpless and complicit status as a powerless bystander to Ginger Roger’s victimization. Baker’s real-life celebrity projects a masterful ownership of the gaze. Moreover, the force of Baker’s look arguably reframes the conventional social relations of power among gender, race, and sexual politics in America’s postwar, pre-civil rights culture.

If it is true, as Hazel Carby has argued, “that white men used their ownership of the body of the white female as a terrain on which to lynch the black male,” 2 then the Storm Warning ad uncannily exposes and collapses the latent lure of this sexual oppression onto the manifest narratives of Klan whippings and mob violence, whose coded signs typically act out the racial oppression of black men, not white women. In stark contrast to this provincial scene, Baker’s stance as a cosmopolitan witness is susceptible to neither its sexual nor racial narratives of violation. Coming full circle, the “frenzy of possession” that originally drives Josephine Baker’s stage artistry, the “primal measures” that haunt Countee Cullen’s otherwise formalist verse refrains, the “passionate gaze” that transfixes McKay’s poet-observer of “The Harlem Dancer,” and the lived affect of what Gwendolyn Bennett discerns in the “surging /Of my sad people’s soul, /Hidden by a minstrel-smile” together testify, by way of a complexly mediated and “masked” performativity, to the traumatic legacy of the middle passage: a transatlantic crossing that Baker, through her performative agency, came to re-cross and so conquer.