|

Walter Kalaidjian,

"Josephine Baker, Performance, and the Traumatic Real"

(page 6 of 6)

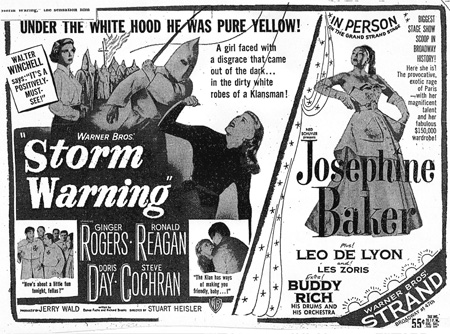

In 1951, Baker commenced her American tour, tied to her civil rights

advocacy and her utopian project of the "rainbow tribe." The force of

her agency in its relation to the traumatic Real can be glimpsed in the

New York Amsterdam News's somewhat uncanny advertisement for her

Broadway stage show at the Strand Theater, performed between viewings of

the Hollywood film Storm Warning featuring Ginger Rogers, Doris

Day, and Ronald Reagan. Briefly, Storm Warning is a 1951 B-movie

that recounts the visit of an urban career woman (Ginger Rogers), to her

pregnant sister (Doris Day) living in a provincial American town lorded

over by the Ku Klux Klan. By chance, Rogers witnesses a Klan murder of a

white investigative reporter and is in turn persecuted by the Klan and

then rescued by the district attorney, played by Ronald Reagan. In the

film's climax, Doris Day's character is accidentally shot and killed by

her Klansman husband, who had perpetrated the murder Rogers had

witnessed.

Following on Baker's successful desegregation efforts at the Copa

City nightclub in Miami, the Amsterdam News observed that "the

pairing of Miss Baker with the Strand's new stirring screen story of the

Ku Klux Klan, Storm Warning, was an indirect tribute to the

artist," a tribute that the paper linked to her service as a secret

agent for the French Resistance during the war.[20] Significantly, in

the ad [Figure 2], Baker as cosmopolitan performer—as a symbol of the "provocative

and exotic rage of Paris"—does not just bear the look of high fashion.

Equally important, the self-possession of her stance reaches beyond the

spectacle of entertainment, leading the viewer's gaze to the scene of

trauma perpetrated by a gang of Klansmen on a white woman, and projects

an agency that sharply offsets Doris Day's helpless and complicit status

as a powerless bystander to Ginger Roger's victimization. Baker's

real-life celebrity projects a masterful ownership of the gaze.

Moreover, the force of Baker's look arguably reframes the conventional

social relations of power among gender, race, and sexual politics in

America's postwar, pre-civil rights culture.

Figure 2 [Back to text]

If it is true, as Hazel Carby has argued, "that white men used their

ownership of the body of the white female as a terrain on which to lynch

the black male,"[21]

then the Storm Warning ad uncannily exposes

and collapses the latent lure of this sexual oppression onto the

manifest narratives of Klan whippings and mob violence, whose coded

signs typically act out the racial oppression of black men, not white

women. In stark contrast to this provincial scene, Baker's stance as a

cosmopolitan witness is susceptible to neither its sexual nor racial

narratives of violation. Coming full circle, the "frenzy of possession"

that originally drives Josephine Baker's stage artistry, the "primal

measures" that haunt Countee Cullen's otherwise formalist verse

refrains, the "passionate gaze" that transfixes McKay's poet-observer of

"The Harlem Dancer," and the lived affect of what Gwendolyn Bennett

discerns in the "surging /Of my sad people's soul, /Hidden by a

minstrel-smile" together testify, by way of a complexly mediated and

"masked" performativity, to the traumatic legacy of the middle passage:

a transatlantic crossing that Baker, through her performative agency,

came to re-cross and so conquer.

Endnotes

1. Michel Fabre describes Josephine Baker as a

"cultural beacon" whose artistry makes her a lasting lieu de

mémoire. See "International Beacons of African-American Memory:

Alexandre Dumas père, Henry O. Tanner, and Josephine Baker as

Examples of Recognition," History and Memory in African-American

Culture, ed. Geneviève Fabre and Robert O'Meally

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 122-149. [Return to text]

2. Gwendolyn B. Bennett, "Heritage," in

Shadowed Dreams: Women's Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance, ed.

Maureen Honey (New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1989), 103. [Return to text]

3. Langston Hughes, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers,"

The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, ed. Arnold Rampersad (New

York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 23. [Return to text]

4. Sterling Brown, "Contemporary Negro Poetry

1914-1936," An Introduction to Black Literature, ed. Lindsay

Patterson (New York: Publishers Co., 1969), 146. [Return to text]

5. See James Clifford, "Negrophilia: February,

1933," A New History of French Literature, ed. Denis Hollier

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), 904. For a discussion

of modern primitivism and Josephine Baker as a modern sauvage,

see James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century

Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press, 1988), 197-200. [Return to text]

6. Paul Gilroy, "'To Be Real': The Dissident Forms

of Black Expressive Culture," in Let's Get It On: The Politics of

Black Performance, ed. Catherine Ugwu (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995),

22. [Return to text]

7. Claude McKay, Selected Poems of Claude

McKay (New York: Bookman Associates, 1953), 61. [Return to text]

8. In Capital, Karl Marx defines the

"mysterious character" of the commodity not according to its physical

usefulness but rather in terms of the "fantastic form" of its exchange

value shaped by its "autonomous" relations with other commodities. "I

call this 'fetishism,'" he writes, "which attaches itself to the

products of labor as soon as they are produced as commodities." Karl

Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Vintage,

1977), 165. For a discussion of how commodity fetishism in the modern

age of photography, film, advertising, and cinematic propaganda marks a

decline in the visible aura of aesthetics, see Walter Benjamin, "The

Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," in

Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn. (London, Fontana, 1992),

211-244. [Return to text]

9. For a discussion of the visual phenomenology of

the traumatic Real experienced in the address or regard of the other's

possessing gaze, see Jacques Lacan, "The Split Between the Eye and the

Gaze," in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Book

XI, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998), 67-78. [Return to text]

10. Pierre Nora, "Between Memory and History:

Les Lieux de Mémoire," History and Memory in African-American

Culture, ed. Geneviève Fabre and Robert O'Meally (New York:

Oxford University Press, 1994), 284-300. [Return to text]

11. In this vein, Paul Gilroy writes that

"[d]iaspora accentuates becoming rather than being. ... Foregrounding the

tensions around origins and essences that diaspora brings into focus,

allows us to perceive that identity should not be fossilized or

venerated in keeping with the holy spirit of ethnic absolutism. Identity

too becomes a noun of process and placed on ceaseless trial. Its almost

infinite openness provides a timely alternative to the authoritarian

implications of mechanical-clockwork-solidarity based on outmoded

notions of 'race.'" Paul Gilroy, "'To Be Real': The Dissident Forms of

Black Expressive Culture," Let's Get It On: The Politics of Black

Performance, 25. [Return to text]

12. Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks,

trans. Charles Lam Markmann (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991), 188.

[Return to text]

13. bell hooks, "Performance Practice as a Site

of Opposition," Let's Get It On: The Politics of Black

Performance, 210. [Return to text]

14. Report to the House of Lords on the Abolition

of the Slave Trade (2 vols; London: 1789), quoted in Lynne Fauley Emery,

Black Dance from 1619 to Today (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Book

Company, 1988), 6. [Return to text]

15. Josephine Baker, quoted in Josephine Baker

and Jo Bouillon, Josephine (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), 1.

[Return to text]

16. Josephine Baker, Josephine, 51-52.

[Return to text]

17. Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental

Concepts of Psychoanalysis, 59. [Return to text]

18. On the resources of melancholia for new modes

of representation and identification, see Loss: The Politics of

Mourning, ed. David L. Eng and David Kazanjian (Berkeley: University

of California Press, 2003), and Judith Butler, The Psychic Life of

Power: Theories in Subjection (Stanford: Stanford UP, 1997). [Return to text]

19. Robert C. Ruark, "She Died on Purpose for a

Cause," Richmond Times Dispatch, March 5, 1951. [Return to text]

20. "The Fabulous Josephine Baker," New York

Amsterdam News, March 10, 1951, 18. [Return to text]

21. Hazel V. Carby, "'On the Threshold of Woman's

Era': Lynching, Empire, and Sexuality in Black Feminist Theory,"

Critical Inquiry 12 (Autumn 1985), 270. [Return to text]

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

|