Josephine Baker, Performance, and the Traumatic Real

Readings of Josephine Baker's cultural status in the twenties

underscore but also tend to limit her stylized performance of the black

body as a modern, primitivist fetish within the registers of colonial

fantasy. For Harlem Renaissance artists such as Gwendolyn Bennett,

Baker's mimicry of primitivist codes, mixed with her mastery of Parisian

cosmopolitanism, was an empowering role model in her own moment. Baker's

performance, of course, would lead her to become a utopian symbol of

progressive celebrity for diverse audiences throughout Europe, South

America, and eventually in the United States, especially in the 1950s,

when Baker was a civil rights pioneer in league with Walter White and

the NAACP.[1]

But from the beginning, the force of Baker's performance

had its source in a psychic register exceeding that of colonial fantasy.

Not just an exotic object or an imaginary bearer of the European

onlooker's desire, Baker emerges as agent, paradoxically enough, by way

of an encounter with a more radically inaugural gaze, one that finds its

source in what Jacques Lacan theorizes in Seminar XI as the traumatic

Real.

To begin with, in her 1923 poem "Heritage," Gwendolyn Bennett

expressed the desire for an African American heritage in the stylized

landscapes of modernist primitivism that would similarly shape the

staging of La Revue Nègre two years later:

I want to see the slim palm-trees,

Pulling at the clouds

With little pointed fingers....

I want to see lithe Negro girls

Etched dark against the sky

While sunset lingers.

I want to hear the silent sands,

Singing to the moon

Before the Sphinx-still face....

I want to hear the chanting

Around a heathen fire

Of a strange black race.

I want to breathe the Lotus flow'r,

Sighing to the stars

With tendrils drinking at the Nile....

I want to feel the surging

Of my sad people's soul,

Hidden by a minstrel-smile.[2]

Here, Bennett conjures Africa through anaphora in the repetition of

the poet's desire not just for the kind of stylized vision of exotic

"palm-trees" derived, perhaps, from writer Claude McKay, but as a more

holistic structure of feeling that involves the five senses. Bennett

insists that she wants "to see lithe Negro girls /Etched dark against

the sky," and to "feel the surging /Of my sad people's soul /Hidden by a

minstrel smile." Moreover, her allusions to the moon's "Sphinx-still

face" and "the Nile" advance the kind of cultural geography of African

location witnessed, for example, in Langston Hughes's celebration of

"the Nile" in "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" as a body of water "ancient

as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins."[3]

Before Countee Cullen's own "Heritage" poem, Bennett imagines the

subversive "chanting /Around a heathen fire /Of a strange black race."

Beyond such primitivist reminiscences, however, the poem is marked by a

coded, and decidedly African American, literary "heritage." Bennett's

"minstrel-smile" which hides "the surging /Of my sad people's soul"

communicates the same "double consciousness" portrayed in Paul Laurence

Dunbar's "We Wear the Mask."

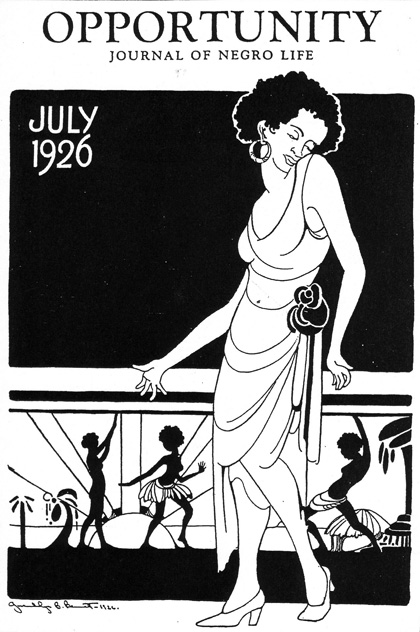

Figure 1

By 1926, Bennett's aesthetic ideology had evolved from what Sterling

Brown described as the New Negro "discovery of Africa as a source of

race pride" to a more cosmopolitan mixing of primitive and modern

aesthetic codes, such as in her cover illustration for

Opportunity. This transition was directly linked to Bennett's

viewing of Josephine Baker's celebrated dance sauvage in La

Revue Nègre the preceding year.[4]

In her visual art, Bennett

presents the modern black dancer as a more ecstatic and self-possessed

version of Baker's cosmopolitan persona that signifies, even as it

masks, a stylized primitivist self. The body language of the racially

ambivalent figure silhouetted in white against a black background

suggestively mimics the bold black celebrants modeled on the moves of

Baker's danse sauvage. Aesthetic primitivism, popularized in the

avant-garde imagination of Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Apollinaire,

Blaise Cendrars, and the Zurich dadaists Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara,

coincided with the influx of African American jazz culture and the

emergence, as James Clifford documents, "of a modern, fieldwork-oriented

anthropology ... at the Paris Institute of Ethnology and the renovated

Trocadero museum."[5]

In critiquing the conjuncture of experimental

modernism, primitivism, and ethnography, Clifford concludes, "the black

body in Paris of the twenties was an ideological artifact" (Clifford

197). Following Clifford, Paul Gilroy also reads Baker as a modernist

minstrel that performed the Eurocentric demand for "escapist

exoticism."[6]

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

Next page

|