|

Jonathan P. Eburne,

"Adoptive Affinities: Josephine Baker's Humanist International"

(page 4 of 6)

The possibility that Baker's adoption practices were fueled by a

cogent theory, and not simply by enthusiasm alone, comes to light in

another of the Scandinavian posters Baker commissioned for Les Milandes

[Figure 4]. In this image, the seemingly backward-looking appeal to

blood ties in fact offers a striking visual metaphor for adoption. Here,

the abstract figures of the children are linked, from heart to heart, by

bands of red, a set of prosthetic collective arteries. The blood

depicted in the image at once naturalizes the poster's celebration of

fraternity—since the figures all share the same blood—but it also

distinguishes this fraternal bond from the functional veins and arteries

of each individual body. The shared bloodstream depicted in the image is

only the supplemental blood of fraternity uniting the figures; it does

not, in other words, represent the mixed blood of miscegenation or, for

that matter, of colonial assimilation. It offers instead a visual

reminder of the children's common bond of love, or, to use Baker's

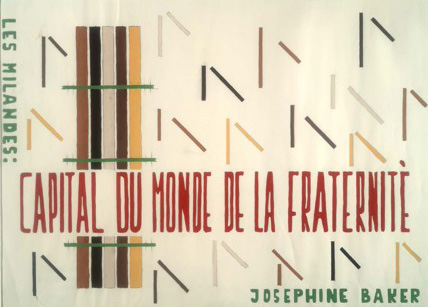

words, their united soul. A related poster design [Figure 5] renders

this adoptive graft all the more explicit: in the image, the swatches of

color representing the variously pigmented children are bundled together

by green bands; rather than invoking the metaphorical sense of blood

ties, the green bands figure kinship as the tidy, organizing knots that

unite the poster's abstract bodies. The uniting bands are, of course,

painted in the same shade of green as Baker's name; yet whereas this

might seem all too handily to allegorize the calculating agency that

guided the formation of Baker's adoptive family, it also suggests,

reciprocally, that Baker's adoptions could instigate the surrogate bonds

of love and "united soul" that would be impossible under existing

political and ideological conditions. Indeed, the significance of

adoption to this graft of a collective humanity upon irreducible

differences of race, religion, and national origin lies precisely in the

non-biological and utterly conscious principle of selection involved in

such adoptive practices.

Figure 4: Courtesy of Emory University Special Collections. [Back to text]

Figure 5: Courtesy of Emory University Special Collections. [Back to text]

Baker's use of adoption as a symbolic political practice is based, I

am suggesting, on what I'd like to call a notion of "adoptive

affinities." The term is derived from Goethe's notion of elective

affinities, which describes chemical properties that force a set of

existing chemical bonds to break up in order to make possible another,

more necessary set of relations. Goethe's novel, Elective

Affinities, introduces this bit of chemical jargon as an analogy for

marital love, emphasizing how a more passionate relationship can

dissolve a more conventional one, as if by choice. In Goethe's case,

this affinity is disturbingly anarchic in its power to destroy as well

as to create bonds of love, and Baker's understanding of adoption bears

a similar sense of the urgency and voluntarism signified in Goethe's

analogy. "In this forsaking and embracing," Goethe writes, "in this

seeking and flying, we believe we are indeed observing the effects of

some higher determination."[12] On the domestic front, the children of

the rainbow tribe were immersed in anecdotes and allegories that strove

to naturalize the kinds of pacts a family of surrogates made possible,

whether this meant a duck adopting motherless chicks, or a dog nursing

an abandoned thirteenth piglet.[13] Narratives aside, though, Baker

recognized that the rainbow tribe had to function as a family in order

to serve as a symbol for the viability of universal brotherhood. As she

wrote in a letter to the producer Stephen Papich in 1964, her children

[h]ave proved that there were no more continents,/ No more

obstacles,/ No more problems which could prevent understanding and

respect between humans,/ No more excuses that color and religious

differences prevent unity.[14]

What permitted such a project was, as much in Baker's case as in

Goethe's novel, the relatively unadulterated social environment of the

rural countryside, which prevented, in Baker's words, the children's

"brotherly education" from being "interrupted by bad spirits."

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

Next page

|