|

Jonathan P. Eburne,

"Adoptive Affinities: Josephine Baker's Humanist International"

(page 2 of 6)

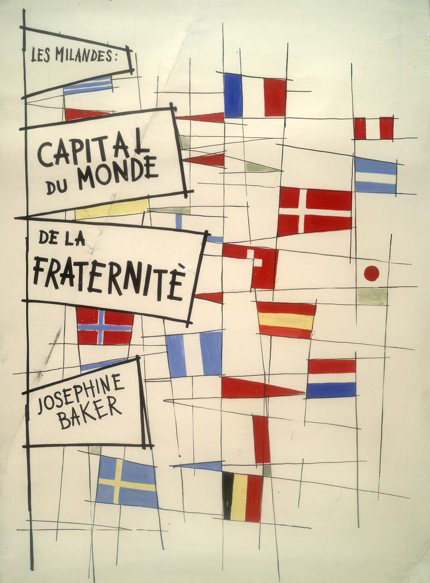

Throughout her postwar career, Baker would tirelessly reiterate the

humanistic mission of her family and adopted village in the French

southwest. Whereas Garry Davis made his case for global citizenship in

explicitly political terms, Baker's practices of adoption seemed to take

place on a more domestic scale. Yet not only did the performer's massive

international celebrity render such domestic practices public, but Baker

herself mobilized this celebrity as a means for establishing the rainbow

tribe's symbolic value as what might be considered a depoliticized form

of political intervention. As one of a number of poster designs for Les

Milandes commissioned in 1958 suggests [Figure 1], Baker promoted the

village as a tourist destination in ways that attempted to build Baker's

"world capital of brotherhood" on the order of the United Nations.[5] The

design, with its jaunty proliferation of national flags, seems even to

borrow the iconography of the U.N. headquarters building in New York,

which was completed in 1952.[5]

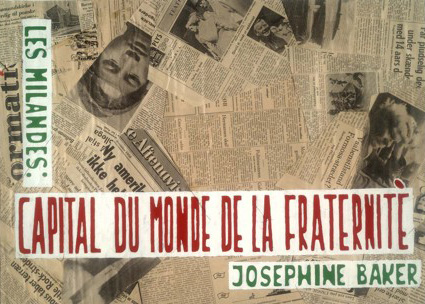

A second poster design [Figure 2],

bearing the same slogan, invokes the media attention itself that Baker

used to fuel her global village, both financially and politically. A

relentless correspondent as well as an oft-interviewed celebrity,

Baker's project relied heavily on her contacts with journalists,

photographers, intellectuals, and dignitaries, yet its ideological and

political stakes were likewise often abstracted, for the same reason. As

Benetta Jules-Rosette has suggested, one of the problems with the design

of Les Milandes, and of Baker's portrayal in the print media, was that

her adoptive project could look more like a celebration of universal

motherhood—with Baker as a saintly Madonna—than a symbolic embrace of

universal brotherhood [Figure 3]. As a result, Baker's artistic and

philanthropic career after the Second World War is often considered a

financially doomed and conceptually limited extension of her interwar

fame, and her on- and offstage performances as based more on nostalgia

than on artistic or political innovation.[7] I would like to propose

instead that Baker's rainbow tribe mobilized both multiracial adoption

and Frenchness in an effort to extend, through symbolic means, her civil

rights activism of the early 1950s.

Figure 1: Courtesy of Emory University Special Collections. [Back to text]

Figure 2: Courtesy of Emory University Special Collections. [Back to text]

Figure 3 [Back to text]

One of Baker's more succinct statements of purpose appears in a

letter she wrote in 1959 to her agent, William Taub, in response to his

request for details about Les Milandes. For each of the ten children she

and Bouillon had adopted by this point, Baker identifies his or her

national origin, religion, race, and age. As she writes:

They each are brought up in their own religion so as to prove that

religion is an expression of the soul and should unite people instead of

separating them and that God is the father of us all.

We adopted these children as an example and a symbol of universal

brotherhood and to prove that people of different colors, continents and

creeds, can live together in harmony and brotherhood, and that with

tolerance, understanding and love there can be a better future for the

world.

Every day, our children prove that our theory was right and these

children give us profound confidence in the future although the world is

confused.

These children are followed closely by special doctors and have been

vaccinated against all diseases including polio.[8]

Adding that all the children would be tutored in their native languages

and would be reintroduced to their native lands by age 12, Baker's

letter emphasizes the extent to which her "rainbow tribe" worked to

preserve, rather than to dissolve, the racial and cultural differences

among the adoptive children. In certain accounts, this characterization

runs into stereotyping, appearing more like the neocolonial small world

of Walt Disney than the domestic embodiment of the United Nations.[9]

One of the most egregious characterizations of the rainbow tribe's racial

and religious "differences" in such terms is also one of the most

prominent: Jo Bouillon's introduction to the posthumous autobiography of

Josephine Baker, which he coauthored, presents the rainbow tribe's

agglomeration of ethnic "types" in memorializing Baker's death.

Remembering Baker as "a woman of a hundred faces," Bouillon writes:

These faces rose before me as I traveled through the darkness to

Josephine's side. And with them came the beloved faces of the children.

Akio, almond-eyed, sensitive, serious; Jarri, with his Nordic fairness

and stamina, Jean-Claude, our blond Frenchman, blessed with an innate

equilibrium; Mara, a full-blooded Indian, who hoped to become a doctor

because they are lacking in his native Venezuela; Janot, the Japanese,

whose love of plants and flowers points toward a career in horticulture;

Brahim and Marianne, found abandoned under a bush in the midst of the

Algerian war, he the son of an Arab, she a colonial's granddaughter;

dusky Koffi from Abidjan, with his purity of spirit [...][9]

Bouillon's litany continues, closing with an image of how the

children's' faces were "overshadowed by images of Josephine, friend of

the rich and poor, the unknown and famous." Not only does Bouillon,

throughout his contributions to Baker's autobiography, portray the

children as appendages of the dancer's personality, but the

sentimentalized racial essentialism of Bouillon's taxonomy also

overshadows the more nuanced ways in which Baker conceptualized the

rainbow tribe.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

Next page

|