|

Daphne Ann Brooks,

"The End of the Line: Josephine Baker and the Politics of Black Women's Corporeal Comedy"

(page 4 of 6)

While I'll return in a moment to the topic of those perpetually

crossed eyes, I want to think a bit more about Baker's mischief at the

end of the line.

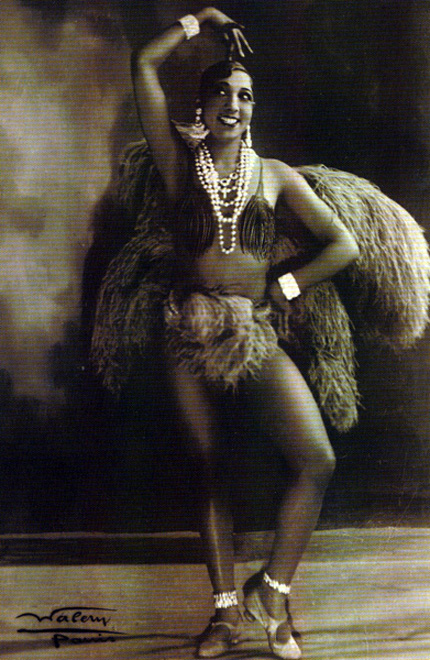

Figure 3

Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Karen Dalton remind us, for instance, that

Baker's moves were both dazzling and disorienting. They point out that

in her breakthrough role as a chorus line girl in Noble Sissle and Eubie

Blake's Shuffle Along, "audiences were bowled over by her

frenetic dancing and outrageous clowning, the visual equivalents of

malapropisms" (910). What, we might ask, does it mean to do the

"wrong" dance at the right time? What are the consequences of

making incongruous gestures within certain contexts?

Such questions should remind us of the points that Margo Jefferson

raises about how one of Josephine Baker's gifts was her ability to

navigate incongruities, to take "contradictory dances and make them one

or even show them operating at the same time." By mixing American

musical theater with blues and jazz phrasings and French music hall

aesthetics, Baker was able to create dissonant humor. This dissonance,

one might argue, emerged out of that end space.[10]

Figure 4

Josephine Baker's end of the line is not just spatial, but

temporal as well. We should recall that Baker's own Topsy incarnation in

the 1924 musical The Chocolate Dandies, Topsy Anna, showcased her

in full "blackface, wearing bright cotton smocks and clown shoes" and

provided her with the platform from which to distort time with her

lightning movements. The poet e.e. cummings, sounding like Charles

Dickens watching the African dancer Juba, would revel in the racist

spectacle of this "'tall, vital, incomparably fluid nightmare which

crossed its eyes and warped its limbs in a purely unearthly manner."

(Dalton and Gates, 911)

While cummings was representative of white spectators who fetishized

what they perceived as physical deviance in Baker's dance style, Baker's

choreography actually amounted to intelligent and inspired aesthetic

design. Anthea Kraut argues that "Baker inevitably seemed to forget the

steps she had been taught" but would wind up "performing her own

idiosyncratic moves in their place."[11] We might think of this gesture

as a kind of choreographic interpellation. By this I mean that Josephine

Baker inserted a kind of dance into a space where it was not

expected.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

Next page

|