|

Daphne Ann Brooks,

"The End of the Line: Josephine Baker and the Politics of Black Women's Corporeal Comedy"

(page 2 of 6)

The Bottom of Power

What kind of multiple meanings does this thespian-inspired,

titillating piece of dialogue possibly suggest? Must 6 hit rock bottom?

Must she create a critical foundation in her life and art with a bottom

on which to stand firm? Or must she perhaps find a way to (re)possess

the eroticism that her bottom represents? Must she discover a means to

avoiding the invisibility of no-bodiness somehow? To escape the

bottomless pit of sexual commodification, the film suggests that Girl 6

must follow the path of Josephine Baker. She must turn the site of

(un)covering into her own fiction. She must, as Baker would famously

proclaim, exploit "the intelligence of [her] own body" for her own

purposes.

The bottom is where I want to begin today and it is, I suggest, one

of several sites where the "intelligence" of Baker's performance

aesthetic lies. It is the bottom that links Baker not only to the words

of 6's acting instructor, but of course to Sara Baartman, the "Venus

Hottentot," a woman whose buttocks and genitalia were dissected and

displayed at the hands of European science and whom Parks surely had in

mind as well when she imagined her heroine's dilemma.[4]

Baartman's sexual exploitation, as Mae Henderson has shown, set a

precedent for the kind of ethnographic spectacle that Baker would have

to navigate in the primitivist frenzy of 1920s Parisian music hall

culture. However, as Henderson makes clear, whereas Baartman functioned

as "pure display ... an icon of black sexuality and the (black) female

sexual grotesque," Baker, removed by a century from Baartman, was able

to turn the static body of black female sexual exploitation into a

dynamic, mobile enterprise.[5]

I want to think in particular about Henderson's important claim that

Baker was "a seasoned comedienne" who "combined a performance of the

erotic with elements of the parodic" (124). I want to walk

through some of the specific modes of comedy that Baker stylized and

perfected—moves that highlight her corporeal elasticity and underscore

the ways in which Baker and other black female entertainers utilized

comic insurgency to wrest their bodies from socio-historical

conventions. Below, I suggest that we might ask what kinds of jokes

Josephine Baker could tell with her body and whether the body is capable

of lobbing a few punch lines.

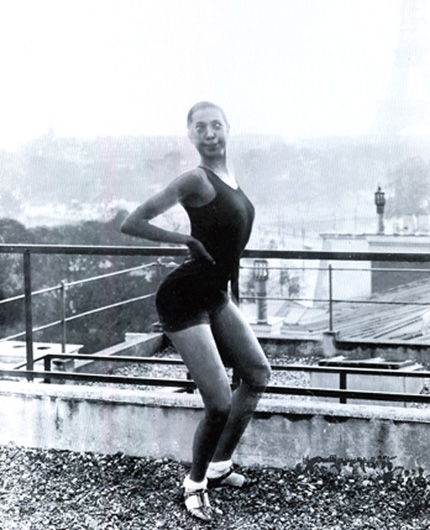

Figure 1

In this regard, I would have us think more about this notion of the

bottom as it literally and figuratively relates to Josephine Baker.

Specifically, I am interested in the "place" of the bottom in black

women's comedic corporeal politics and the ways in which we might extend

this concept of the bottom to refer not only to the physical body of the

black woman but to other ends that reveal her innovative comedic

strategies of gestures and corporeal eccentricities. Read from this

perspective, we can consider the ways that Baker's body perhaps

re-oriented the spectacular attention directed at black female bodies in

public spaces and potentially disabled the kind of exploitative

spectatorship that circumscribed Sara Baartman.

As bell hooks has made clear about Baker's body, "one can hardly

overemphasize the importance of her rear end." Baker herself reportedly

argued that the "rear end exists ... I see no reason to be ashamed of it."

Hooks thus contends that with "Baker's triumph, the erotic gaze of a

nation moved downward: she had uncovered a new region for desire."[6]

But we might move from this physical region of "plenty" to consider

its metaphorical dimensions. Perhaps, when we think about Josephine

Baker, we're dealing not just with the triumph of a physical black

bottom on display, but with other kinds of ends and posterior spaces as

well. Baker was all about the end, I would argue, but her genius

surfaced most brilliantly in choreographic tales/tails that exceeded the

frame of her body.

If we think, for instance, of these alternative endings as spaces

that yield the kind of gestures that Carla Peterson terms

"eccentric"—"an empowering oddness" and "a notion of off-centeredness"

that suggests "freedom of movement" for black female performers,[7]

we might move then from ends to Josephine Baker's eccentric means so as

to interrogate the specific gestures that she utilizes to disable, to

disrupt, and to deflect more limited regimes of looking.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

Next page

|