|

Daphne Ann Brooks,

"The End of the Line: Josephine Baker and the Politics of Black Women's Corporeal Comedy"

(page 3 of 6)

The End of the Line

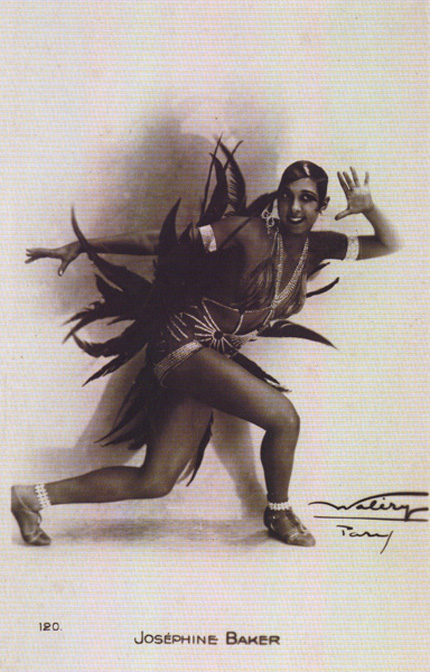

Figure 2

We know from Jayna Brown's brilliant forthcoming study of early

twentieth-century black female performance culture that Baker was one of

many working black female entertainers at the dawn of the Harlem

Renaissance who experimented with counter-hegemonic forms of modern

dance that generated "satirical comment on the absurdity" of "spurious

racialisms."[8]

By Brown's account, these female pioneers of black dance—women like

Ida Forsyne, Ethel Williams, Baker, and many others—actively transformed

canonic blackface roles through their own innovative movements on the

stage. In the hands of these women, iconic minstrel caricatures—from

nameless "pickaninnies" to Harriet Beecher Stowe's Topsy—transmogrified

into tools of farce that had the power to "disrobe authority" (7). As

Brown has persuasively argued, "Topsy has a keen sense of time, as her

body has been marked by the uses to which her body, and the bodies of

other slave children, was put. Topsy has no investment in keeping the

'master's time.' She contorts and bends it—syncopates it, rags it,

swings it.... She creates play zones out of its distortion. Pushing at

boundaries of time's rhythmic containing, the dancing slave takes time

out of its routines, its disciplinary actions on her body" (Chap 2,

41).

Baker got her start in theater by performing these Topsy-like, black

vaudeville minstrelsy roles, but she came to stardom extending the

innovations of Ethel Williams, as several cultural critics have duly

noted. It was Williams who first stylized the routine that became known

as the "mischievous girl at the end of the [chorus] line," and Baker

would later follow suit. As Brown reminds us, Williams "refused to toe

the line." And as Williams puts it, "'I would be doing anything but

that. I'd do the 'ball the jack' on the end of the line every kind of

way you could think about it. When the curtain came down, even my

fingers were doing ball the jack outside [the curtain]'" (Chap 2, Chap

5, 10).

Baker would later gain great notice for following Williams's moves.

As one contemporary reviewer remarked of Baker's performances, "she was

the little girl on the end. You couldn't forget her once you'd noticed

her, and you couldn't escape noticing her. She was beautiful but it was

never her beauty that attracted your eyes. In those days her brown body

was disguised by an ordinary chorus costume. She had a trick of letting

her knees fold under her, eccentric wise. And her eyes, just at the

crucial moment when the music reached the climactic 'he's just wild

about, cannot live without, he's just wild about me' [from "I'm Just

Wild About Harry"], her eyes crossed."[9]

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

Next page

|