|

Connie Samaras,

"America Dreams"

(page 6 of 7)

The notion of the heroic is also complicated. There are, of course,

those laboring under the weight of their own egos and conventional ideas

of masculinity. But, especially among the support staff, there are many

others, both women and men, to whom one can trust one's life, people who

see survival as a matter of interdependency and heroic actions as a

potential necessity, not a Romantic narrative of winners, losers and an

audience of hero worshippers.

Figure 11 Connie Samaras

Angelic States—Event Sequence: StarTrek Casino Las Vegas

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

The feminist gesture behind my photographs is not always overtly

evident in the initial reading of the images. This is especially so as

here I avoided photographing figures because it is often easier to read

architectural narratives without picturing inhabitants. For some time

now, regardless of subject matter, I've been interested in the idea of

positionality, one case in point being the shifting constructions and

circumstances of the body behind the camera. In one prior project

on U.S. urban landscape (Angelic States—Event Sequence,

1998-2003), almost all the places I photographed were off limits to

cameras. I dealt with this by playing into the gendered assumptions

surrounding the person people thought they were seeing behind the

camera. For example, when guards approached me for photographing inside

a casino, I took on the persona of a timid housewife whose husband had

assured her that photography was allowed (see Figure 11).

In Antarctica, in my

position as "the photographer," I anticipated that how some would

perceive me would be dependent on whatever technology I was seen using.

For example, although many were respectful of the fact that I knew what

I was doing, when I began to work first with the smaller cameras I

brought, a number of "polies" offered unsolicited opinions as to how I

was using the wrong lens or the incorrect camera body. Part of it

might have had to do with the fact that despite being queer and white, I

was still the wrong silhouette and shade (short, olive, and curvy) for

the explorer's body and the polar gear issued to me. I may have looked

more like Kenny on South Park than Ernest Shackleton, but when I

brought out the 4x5 camera and black focusing cloth, thus "borrowing"

the mantle of Robert Scott's official photographer George Herbert

Ponting, it was only then that the unwanted suggestions stopped.

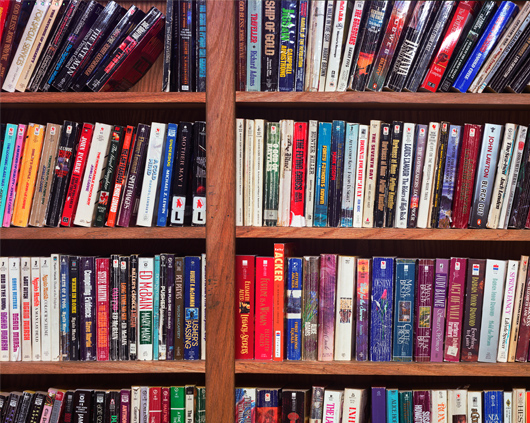

Figure 12 Connie Samaras

Dome Library

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

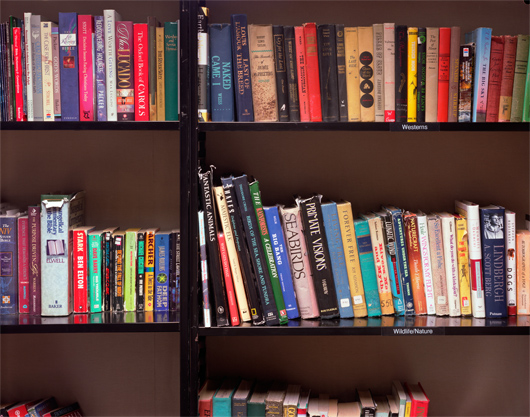

Aside, however, from how the body is enacted while taking pictures, I

also made a decidedly feminist edit when taking photographs of the then

two libraries: the one that was soon to be dismantled in the Dome and the

other that was being newly assembled in the Amundsen-Scott building. A

comparison of the libraries reveals the differing cultural histories of

the structures. The Dome's collection was a diverse range of books from

pulp to experimental fiction, from western classics to political theory.

At the time I was there, the new library was not as eclectic and, in

stark contrast, had Christian religious texts peppering the shelves no

matter what the category. However, the embedded focal point of my

images was how contemporary women authors had been mis-categorized in

both collections. In the Dome library, shelved under the "Romance"

section was Kathy Acker's In Memoriam to Identity while in the

new station Donna Haraway's Primate Visions had been placed under

"Wildlife/Nature" (see Figure 12 and Figure 13).

Figure 13 Connie Samaras

Amundsen-Scott Library

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

There is a sort of intractable neutrality when it comes to discussing

and imagining Antarctica. A few scholars, like Bloom, have rigorously

grappled with the erasures, untruths, origins, and functions of such a

perception. But I was puzzled by my own experience of it while there,

as though I was a metal particle being drawn to a magnetic field. Part

of it I could attribute to the relentless culture of rationality in

scientific enclaves. However, because I was interested in the

unconscious architectural messages—Why space operates as the source of

SF inspiration? Why not the heterotopias of Samuel Delaney, the

critiques of scientific investigation of Stansilaw Lem, the near futures

of Octavia Butler where change is the only constant, or the gender

twists of James Tiptree Jr.?—I didn't feel that my immersion in a

culture of objectivity fully explained this pull. In retrospect, part

of it has to do with the fact that any political questions including

gender are endlessly open ones, subject to historical and cultural flux.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 |

4 | 5 |

6 | 7

Next page

|