|

Connie Samaras,

"America Dreams"

(page 2 of 7)

These dreams reveal, in part, my aesthetic preoccupation with

SF,science/speculative fiction, mostly as it pertains to how the U.S.

dreams itself at various junctures. Given that SF is a literary genre

central to the United States, some have commented, such as writer Claire

Phillips, that perhaps SF is to this country what magic realism is to

parts of Latin America. Although preceded and influenced by the

writings of the British 19th century futurists, U.S. science fiction was

first formalized in 1926 with the publication of Hugo Gernsback's

magazine,Amazing Stories.[1]

Over the decades, SF has evolved

(as well as de-evolved) past Gernsback's initial editorial dictates that

all stories in the magazine must include accurate portrayals of

technology as well as masculine heroic trajectories. The title of the

series of works I did in Antarctica, V.A.L.I.S. (vast active living

intelligence system), borrows its title from the decidedly

anti-heroic, psychologically-centric science fiction work of Philip K.

Dick, writings which are often populated by failed men and underscore the

fact that technology is, in and of itself, dumb, and that intelligence,

whether organic, mechanical, or a combination of the two, is subject to

multiple forms of symbolic order and slippage.[2]

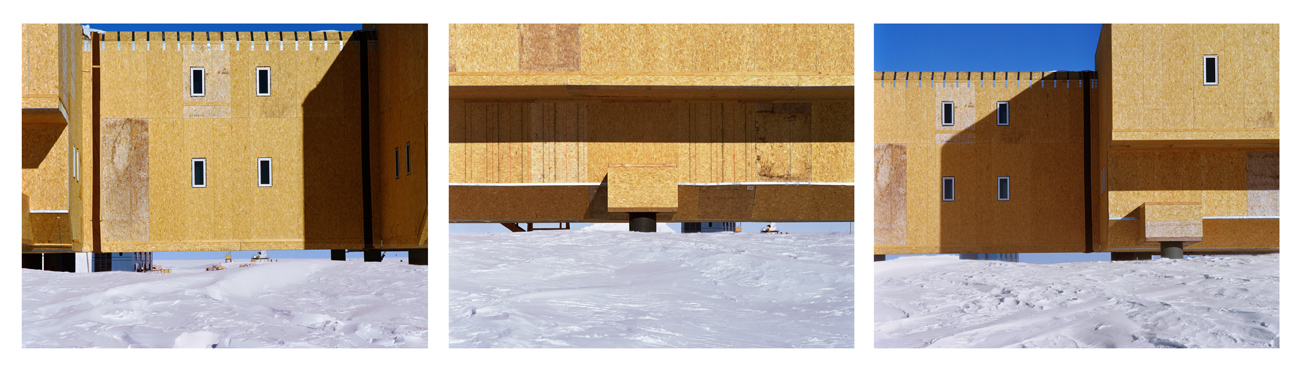

Figure 1 Connie Samaras

Amundsen-Scott Station Phase III (triptych)

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

Although Dick's V.A.L.I.S. is part of a semi-autobiographical trilogy

related to his religious conversion in later years, my appropriation of

his title was more out of a shared interest in the overall ideas that

run throughout Dick's writings of transcendence and technology, the

ability to perceive multiple timelines and realities, and the ever

shifting membrane between fiction and the real world. Part of what

interested me at the Pole are the different ways in which the U.S.,

since mid-century, has architecturally envisioned both the future and

the colonizing of spaces where there are no indigenous peoples. While

the U.S. station is optimally positioned should the non-sovereign

Antarctic treaty unravel, few countries can afford to build at the South

Pole given the constant drift and movement of the ice. No matter how

smart the engineering, ice covers any built environment there in 40 or

so years. Moreover, the geographic center of the Pole is also in

constant flux. Even if a building could last more than a century,

within three decades it would no longer be near the geographic center.

While at the South Pole, I felt a poetic relief as I observed and

documented the geological timeline indifferently erasing attempts to

colonize the polar plateau. However, witnessing the ultimate trumping

of the ice over occupation also left me with an overwhelming feeling of

taking on a project that could not be completed. At first somewhat

paralyzing, I later came to (once again) realize that there was no whole

to be had (the mental space of empire) but rather the more "realistic"

approach was to chart the shifting juxtapositions between landscape and

built environment as fragmented and momentary.

Figure 2 Connie Samaras

Detail Figure 1, panel 1 from Amundsen-Scott Station Phase III (triptych)

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

In some ways this was an intentional counterpoint to the typical,

historical impulse to photograph such vast landscapes panoramically.

For example, one often sees photographs of the Pole shot with a

"fisheye," the widest of lenses, an understandable inclination. Because

photography is driven by realism (much contemporary art photography has

been about disrupting this assumption), the visual desire is to capture

as much of the vista as possible into a single frame. The result is

hardly realistic. The unnatural bending around of the image caused by

the fisheye's optics (as though the curvature of the planet is wrapping

itself in the opposite direction) only underscores the artificiality of

any form of representation. This normalized lure of the panorama can

also be attributed to its longstanding history as the first Western

virtual tourist space. Two hundred years ago, Europeans paid to immerse

themselves in tunnels of painted panoramas of places to which they could

never travel. The South Pole, a location accessible to only an elite

few, seems to "naturally" lend itself to a form of representation

developed in an era when the majority of Europeans rarely ever traveled

more than a few kilometers from home.

Figure 3 Connie Samaras

Detail Figure 2, panel 2 from Amundsen-Scott Station Phase III (triptych)

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

Although not shot as panoramas, most of the photographs in the

V.A.L.I.S. series are printed in mural size. The images are also

formally constructed using a type of abstraction reminiscent of

mid-century U.S. modernist architecture and painting. Most are shot

with a long lens in order to play to the disorienting sense of scale

between the landscape and structures that occurs when buildings are

viewed close-up.

Figure 4 Connie Samaras

Dome Interior

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

The images are also composed to appear as alternating filmstrips of

abstraction and realism, as a means to visually entangle the binary of

real world and fabrication. Although I draw somewhat from the style of

contemporary German photography first associated with Bernd and Hilla

Becher, and sometimes termed "deadpan," my interest is more in the

paradoxical and interdependent relationships between documentary and the

imaginary than it is to construct a wholly unsentimental

image.[3] Yet,

some of the images, such as the triptych of the new Amundsen-Scott

Station under construction, do appear "cold" and lacking in emotion

(see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Conversely, others, such as the "Dome Interior," appear "warmer," but no less

visually confusing (see Figure 4). The reason for the

difference in semiotic temperatures between photographs is related to

the variation in design and tropes of modernity during the particular

decade in which a given station was erected.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 |

4 | 5 |

6 | 7

Next page

|