|

Gísli Pálsson,

"Hot Bodies in Cold Zones: Arctic Exploration"

(page 5 of 7)

Coming Out

While Stefansson seems to have had a close relationship to his Inuit

wife and son when in the field, once he was "out" he never publicly

acknowledged his Inuit family. His denial, no doubt, is one example of a

fairly common imperial response. At the time, white guests simply did

not acknowledge intimate realtions with indigenous people if they had

serious ambitions outside the colony. Not only did Stefansson's Inuit

connection defy prevailing attitudes toward "race mixing", his prior

engagement to a woman he met while in Boston, Orpha Cecil Smith, a

Canadian student of drama (see Pálsson 2005), made things rather

complicated. Stefansson, it seems, was anxious not to tell Smith about

his Inuit son. Her father was religious and middle-class, a salesman of

Canadian Mennonite background, and disapproving of his daughter's

relationship to Stefansson, a man who seemed destined for pointless and

risky adventures among savages in the Arctic. Smith and Stefansson were

engaged at the time Alex Stefansson was born. Inevitably, the long

separation was taxing for their relationship. In Smith's memory,

Stefansson disappeared out of sight when he left for the Arctic although

they were to meet again. They exchanged intimate letters throughout the

three expeditions, to the extent this was possible due to the logistics

of the expeditions and the sporadic nature of the postal service at the

time.

We do not know what Stefansson thought of his relationship with

Pannigabluk and Alex as he doesn't mention either a partner or a child

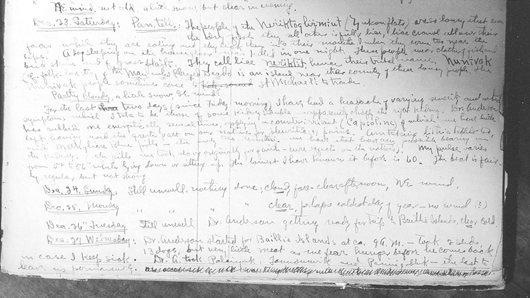

in any of his writings. Some of his diary entries, however, indicate a

rupture in his relationship to Pannigabluk (see Pálsson 2005: 88). On

December 27 in 1911 he writes that Pannigabluk is leaving "permanently"

(see Photo 3). He appears to have added something more to this, but later

crossed it out carefully. Was it out of frustration? Could it be that

Pannigabluk was leaving Stefansson for another man? Late in his career,

Stefansson married a young woman in New York. His widow Evelyn (now

Stefansson Nef) has sometimes attributed his silence on Alex Stefansson

to the possibility that Pannigabluk may have been involved in sexual

relations with another member of Stefansson's expedition (Andersen).

While such a claim may have relieved Stefansson and his widow of any

responsibility with respect to his son and his six grandchildren, it

seems unconvincing (see Pálsson 2005); many Inuit, including his

grandchildren, suggest it was just an excuse. A recent article by

Vanast (2007) turns the gaze onto Stefansson himself.

Photo 3 Stefansson's diary entry about Pannigabluk's departure.

(Dartmouth College Library).

Vanast suggests that Pannigabluk may have left the camp in an angry

mood, jealous because of Stefansson's sexual liaisons with other women;

while the evidence may be indirect, he argues, "comments by whites (when

combined with dates on which one finds Stefansson in the company of

certain wives) make for strong suspicion" (2007: 93). Prior to

Pannigabluk's departure, Vanast speculates, Stefansson had been involved

with a woman named Mamayauk and her twelve-year-old daughter Nogasak.

Stefansson had last seen Pannigabluk in March 1911 when he left for the

Copper Inuit and when he returned in June "she was not there, but he did

find Ilavinirk, his wife Mamayauk, their young daughter Nogasak, and

another male. In July the men left for Baillie Island. ... Stefansson

was alone with Maayauk and Nogasak until, a fortnight later, Pannigabluk

appeared . . .. That winter . . . Stefansson spent much time with Mamayauk

(whose husband had returned) and little with Pannigabluk, who left the

camp for good . . ." (Vanast 2007: 108, n. 13).

It seems that Stefansson sometimes arranged to have access to women

other than Pannigabluk. Not only did he admit that he hired males who

contributed little because he needed their wives as seamstresses, at one

point he would spend time "drawing from his employees the names of the

prettiest women in the Delta region" (Vanast 2007: 93). Whites claimed

that he "chose men whose partners were renowned for their beauty, even

'crazy' men" (Vanast 2007: 93). One of the women in Stefansson's

entourage in 1915-1917 was a woman in her twenties, the wife of Walter

Pikaluk who worked for Stefansson when 40-42 years old. Vanast continues

in a footnote: "In mission records her name appeared as Bessie

Poochimuk, Puchimuk, or Puchimirk . . .. It may be entirely unfair to

Stefansson to note that he referred to her in his diary . . . as Pussimirk"

(2007: 109, n. 14). There is a long tradition of Stefansson-bashing in

Canadian academic circles. It may be tempting to see Vanast's commentary

as just one more example in this genre, echoing earlier debates about

Stefansson's flamboyant style, waste of public money, lack of judgment,

and irresponsible behavior. Although the evidence discussed by Vanast is

anecdotal and circumstantial and he may overstate his case, he

nevertheless seems to have a point. It is quite likely that Stefansson's

silence about his Inuit wife and son had something to do with his

complex involvements with other women in and out of the field.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7

Next page

|