|

Gísli Pálsson,

"Hot Bodies in Cold Zones: Arctic Exploration"

(page 2 of 7)

Herschel Island

The early zoning of the earth into regions or culture-areas

underlined Western ideas about borders, cultural differences, and the

exotic. The "Arctic", however, neither had clear boundaries nor a firm

definition. For some, it represented anything beyond latitude 66°33'

north, for others it began with the tree line, and for still others it

was identified by average temperature. For most Western whalers, early

explorers, and anthropologists, the Arctic was a radical other. This was

underlined by frequent references in Western discourse on the Arctic to

"going in" and "coming out", indicating that civilization ended where

the Arctic began. Despite their othering of the people of the Arctic,

European travelers often formed intimate relations with their indigenous

collaborators, relations without which they would not have survived. The

loosely defined Arctic Circle continues to be deeply enmeshed in the

geopolitics of northern states and international bodies focusing on

development, resources, and climate.

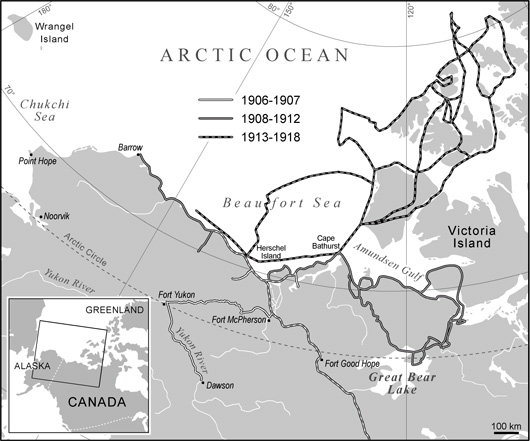

One of the key sites in the exploration and colonization of the

Canadian Arctic was Herschel Island, located a few miles from the arctic

coast close to the Mackenzie Delta (see Map 1). The number of guests who

wintered there, mostly in relation to whaling, peaked soon after 1890,

with approximately 1500 people. The Inuit living on or near the island

provided European whalers with food and clothing in return for southern

goods, including tea and sugar. Many accounts of local life dwell on

stories of drinking and fighting. The main reasons for the expansion of

the settlement at Herschel Island had to do with changes in fashion and

morals in Europe. Among women of the aristocratic classes, wide and

flexible dresses had increasingly been replaced by more firm and

restricting clothes. Sometimes they were carefully tightened around the

waist to underline the Victorian forces applied to women's minds and

bodies. Corsets, especially when strengthened by whalebone, baleen, were

seen to be useful for this purpose. The French elite spoke of "Corps

Baleine". The growing market for corsets invigorated the whaling

industry at Herschel Island. The price of whalebone increased and the

operation of whaling boats became a lucrative business, even under the

difficult conditions of the Arctic. Ironically, Victorian ideas about

the clothing and constitution of women's bodies were the driving force

behind the development of the whaling community on Herschel Island, a

community that apparently posed a fundamental contradiction to the

virtues that the corset symbolized in Europe.

Map 1 Stefansson's field. (Drawn by Lovísa

Ásbjörnsdóttir).

Over the years the whalers on Herschel Island—a mixed group of

Whites, Afro-Americans, Siberians, Inupiat, and Cape Verdeans

("Portuguees")—established a colorful, multicultural colony on

Herschel Island. Hundreds of whalers arrived from the south, with their

goods, languages, desires, beliefs, and diseases (notably measles,

tuberculosis, and syphilis). There was racial tension between

southerners as well as between guests and natives. In 1884, a few wives

of whaling masters wintered on Herschel Island, along with their

children. While this had a noticeable impact on social life, normally

the whalers arrived without their families. Inuit males often worked as

hunters or mates and Inuit women as seamstresses, either "on deck" or

"below deck", as "seasonal wives". Suddenly, when the whaling stocks had

nearly collapsed and hunting was no longer economical, they were all

gone. In the process, however, Canada had expanded its empire. And for

the Inuit life would never be the same. For almost twenty years, roughly

from 1890 to 1908, Herschel Island was a frontier boom-town, known as

"The Sodom of the Arctic". Many of the European explorers and travelers

who passed through here and elsewhere in the Arctic had native wives or

concubines, including Peter Freuchen, Knud Rasmussen, and Vilhjalmur

Stefansson.

One of the characteristics of the colonial era in the early stages

was the relative absence of women in the colonies. This invited complex

problems both at home and abroad. What rules should be applied to the

intimate and the "private"? Often, the dark sides of colonialism—the

tension between races, the problems of orphanage, and illegitimacy—were

barely noticed. The mixed-blood children of colonial servants and

native women posed a particular classification problem, a problem that

usually was simply ignored. Stoler describes the silencing of emotions

and passions and their consequences as "stubborn colonial aphasia"

(2002: 14). Nevertheless, these were important issues in the biographies

and histories of the colonial world. In some of the colonies, including

the Dutch ones, European children were strictly forbidden to play with

the children of servants of another race. Their moral strength, it was

assumed, would be eroded if they began to babble in the native language.

In the long run, this would lead to racial mixture that, in turn, would

lead to the degeneration of the white race. Stoler's work seeks to

outline the "microphysics of colonial rule" (p. 7) through a colonial

reading of Foucault, exploring "what cultural distinctions went into the

making of class in the colonies, what class distinctions went into the

making of race, and how the management of sex shaped the making of both"

(p. 16).

Much of what Stoler has to say about empires, gender, race, and

intimacy applies to the society of Herschel Island at the beginning of

the last century. In particular, European women were rarely part of the

teams of whalers and explorers. The likelihood of women visiting the

Arctic in the early stage of colonizing was minimal, much less than in

the case of the Tropics. The fiancées, wives, and children of European

travelers invariably stayed behind, usually on the grounds that the

environment and the tasks ahead were too tough for them. Native

seamstresses on the other hand had an important role to play in

exploration parties. Beside sewing warm clothes, preparing food, and

taking care of camps, they provided company and sexual pleasures. Often

guests and natives formed intimate relations and occasionally the guests

married and decided to stay for good.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7

Next page

|