|

Chris Cuomo, Wendy Eisner and Kenneth Hinkel,

"Environmental Change, Indigenous Knowledge, and Subsistence on Alaska's North Slope"

(page 2 of 9)

Context and Methods

Located on the coast of the Arctic Ocean and extending south up to

several hundred kilometers to the Brooks Range, the North Slope Borough

is a petroleum rich area covering the northernmost section of the state

of Alaska. The North Slope Borough is the largest political subdivision

in North America, encompassing fifteen percent of Alaska's total land

mass, with a total of 89,000 square miles, an area just a bit larger

than the state of Minnesota. Approximately 74% of the North Slope's

7,555 residents are Iñupiat Eskimos, the indigenous inhabitants

of the land, and close linguistic and ethnic relatives of the Inuit of

Canada and the Kalaallit of Greenland. The Borough is primarily rural,

although it includes the city of Barrow (the Borough seat, population

4,429), seven smaller villages, and Prudhoe Bay, the

petroleum/industrial complex at the top of the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline

System. Also included within the boundaries of the North Slope Borough

are areas of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and a 23-million acre

area designated as the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPRA), where

oil exploration and drilling are administered by the federal Bureau of

Land Management in accordance with the Naval Petroleum Reserve

Production act of 1976.

The landscape, climate, and native species of the North Slope have

been objects of intense study for decades, for alongside the economic

and political interests in its resources and "strategic" location, the

region's unique geographic, atmospheric, and biological features are of

great ecological and scientific significance. An extensive Naval complex

(the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory) was constructed just north of

Barrow in the mid 1940s to serve oil exploration, and until 1980 it also

served as a base for conducting biological and geological research in

the Arctic.[14]

The current occupant of the site of the former Naval

complex is the Barrow Area Science Consortium (BASC), a science facility

funded by the National Science Foundation, formed through a partnership

of the North Slope Borough, The Ukpeagvik Iñupiat Corporation

(the corporation representing the economic interests of the

Iñupiat of Barrow), and Ilisagvik College (the region's tribal

college). Since 1995 nearly all of the scientific research conducted

near Barrow has been done under the auspices of BASC.

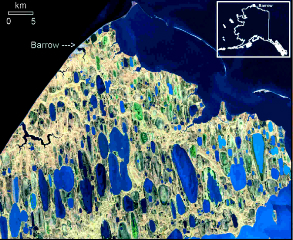

Figure 1

The existence of a science station with firm ties to sturdy sectors

of the local community helped create the conditions for the development

of our research. For several years some members of our team had been

studying the "thaw lakes" and drained lake basins that together cover

about 46% of surface of the Western Arctic Coastal Plain (see Figure 1).

Thaw lakes are formed when water ponds atop underlying, impermeable

frozen ground, or permafrost, and they are the dominant geomorphic

features in the northernmost regions of Alaska, Siberia, and Canada. A

thaw lake drains in response to ice-wedge erosion, bank overflow, stream

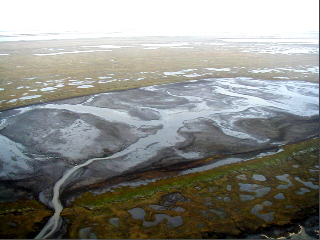

piracy, or breaching of the lake margin (see Figure 2). Drained lake basins

are among the primary reservoirs of carbon in northern Alaska, and so

understanding the lakes, and how they form and drain, is necessary for

determining how carbon accumulation rates respond to regional changes in

climate, and the extent to which warming temperatures will result in

releases of greenhouse gases into the global atmosphere. Our team's

research utilizes the sophisticated tools of physical geography,

including high-resolution multispectral satellite data,

ground-penetrating radar, extensive coring, radiometric dating, and

microfossil analysis, to estimate the amount of carbon sequestered in

the drained basins.[15]

Figure 2

In 2002, one scientist on our team gave a community presentation in

Barrow on thaw lake process as part of an NSF-funded community outreach

project. The subsequent discussion elicited a helpful response from an

Iñupiat elder who worked as community liaison for BASC. She

remarked that local understandings of thaw lake drainage differed

somewhat from the scientific theories, and suggested talking with local

elders. Prompted by that suggestion, in the following field season we

conducted videotaped interviews about the lakes and landscape of the

surrounding areas with several elders in Barrow and Atqasuk, a small

inland village sixty miles to the south of Barrow.[16]

In the initial

interviews, some recalled family stories of rapid lake level changes

near traditional summer hunting camps, and others described drainage

events that were induced by their own activities, such as bank

breaching.

In interviews, elders shared scientifically interesting and

consequential information about thaw lakes. They also volunteered

personal memories and accounts of cultural traditions, and responded to

general questions about local environmental conditions with engaged and

detailed accounts of changes in the landscape, animal migration

patterns, and weather. As in many indigenous communities, Iñupiat

elders hold a repository of knowledge about traditional culture and

local history entwined with their knowledge of the landscape. Northern

Alaska has experienced rapid and dramatic change in the last century,

and there is a strong sense that elders' unique knowledge is extremely

valuable but in danger of being lost. Interviewees and their families

therefore expressed positive feelings about having interviews recorded,

and encouraged us to make videos of interviews available to younger

people in their communities. Videos and other documents are thought to

be useful for preserving the traditional, cultural, and historical

knowledge possessed by elders, as well as their memories, stories, and

linguistic expertise. Because the North Slope school system places some

emphasis on teaching traditional knowledge, there is an existing context

available for sharing archived materials.

We were able to corroborate the timing of observations of past lake

drainage events using satellite imagery, confirming our sense that the

elders had a wealth of relevant knowledge. The combination of compelling

data and community needs led us to develop a research project that

would bring together experiential and scientific knowledge to answer

specific questions about thaw lakes on the North Slope. Another primary

goal was to help document elders' experiences, reflections, and

ecological wisdom in a way that would be useful and accessible to their

community. As an interdisciplinary team, we also had questions and

research interests beyond the explicit focus on thaw lakes. For example,

we were interested in the ways that interviews with Iñupiat

elders might contribute to better understanding of environmental ethics

in the Arctic, where an exceptionally demanding context has led to the

development of human cultures that seem to exemplify "wise use"

paradigms for relationships with nature. And although information about

gender was not likely to be central in our findings about the thaw lake

cycle, we saw this project as an opportunity to implement feminist

methods, such as collaboration across epistemic and cultural

differences, and the intentional inclusion of marginalized and

underrepresented perspectives. Our own perspectives are informed by the

view, most fully articulated in feminist philosophy, that members of

distinct social groups have "epistemic authority," or unique and

important knowledge about their own lives, their social and

environmental contexts, and the issues with which their material and

emotional experiences put them in close contact.[17]

Feminist theories of the epistemic advantages of marginalized or

subordinated perspectives emerged in the late 1970s as women began to

apply Marxist theories of the advantaged and revolutionary perspectives

of workers to the state of women in sexist societies. As Nancy Hartsock

succinctly put it, "Each division of labor, whether by gender or class,

can be expected to have consequences for knowledge."[18]

Gendered differences in knowledge or access to knowledge are not considered

natural or absolute. Rather, they emerge from the material conditions

that are created and enforced through divisions of labor.

The material specificities of regional and cultural differences also

have consequences for knowledge. On the North Slope, indigenous elders

and others with experience on the tundra have epistemic authority

regarding the environment where they have lived, learned, and traveled

for many years. Important knowledge about the state of that environment

will be neglected if those local experts are not consulted. In addition,

history shows that unequal power dynamics are replicated when local

knowledge and impacted communities are not considered worthy of respect

by powerful agents (such as government-funded scientists). Regarding the

potential role of science itself in disrupting unequal or damaging

dynamics, philosopher Sandra Harding writes, "It is scary to contemplate

how the power that Western sciences and technologies make available is

likely to result in increased destruction to humans and our

environments—and especially to economically and politically marginalized

humans and environments—unless this power can be harnessed quickly to

work on agendas for more democratic world communities."[19]

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 |

4 | 5 |

6 | 7 |

8 | 9

Next page

|