Editor’s Note: The following portraiture essay, “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Guyana’s Amerindian Women,” by Khadija Benn is an edited excerpt from the recent book Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora. 1 The book offers an intimate exploration into the migration narratives of women of Guyanese heritage. Its curator and editor, Grace Aneiza Ali, shares an introduction below.

Introduction

by Grace Aneiza Ali

My book, Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora, traces the migration path of Guyanese women from their motherlands to their moment of departure to their arrival on diasporic soils to their reunion with Guyana, and all that flows in between. The book centers the narratives of grandmothers, mothers, daughters, immigrants and citizens, women who have labored for their country, women who live in service to a vision of what Guyanese women can and ought to be in the world. The narratives featured in Liminal Spaces counter a legacy of absence and invisibility of Guyanese women’s stories. The collection—the first of its kind—is devoted entirely to the voices of women from Guyana and its expansive diaspora. Their stories speak to migration as the defining movement of our twenty-first-century world, highlighting the tensions between place and placeless-ness, nationality and belonging, immigrant and citizen.

Etched throughout the book’s literary and visual narratives is the grit, agency, and artistry required of women around the world to embark on a new life in a new land, or to watch the ones they love do so. Within these beautiful, disruptive stories lies a simple truth: There is no single story about migration. Rather, the act of migration is infinite, full of arrivals, departures, returns, absences, and reunions. There are two spectrums of the migration arc: The ones who leave and the ones who are left. The act of migration is an act of reciprocity. To leave a place, we must reconcile ourselves to the fact that we will leave others behind. Yet in narratives of migration, the stories of those who are left are constantly eclipsed. Consequently, at the core of my curatorial practice and scholarship on art and migration is a belief that we must counter the overwhelming focus on the ones who leave with the stories of those who remain.

I invited Khadija Benn to contribute to Liminal Spaces because her work centers the stories of those who are left. Benn is among the few women photographers living in Guyana who chooses to forge an artistic practice in the country. As a geospatial analyst, Benn often journeys across Guyana to remote places where most Guyanese rarely have access. These small villages are central to Benn’s stunning black and white portraits of the elder Amerindian women who call these communities home. However, as she emphatically notes in “Those Who Remain,” the portraiture essay in Liminal Spaces and excerpted below, these are not invisible women. Benn’s adjoining passages from her interviews with the Amerindian elders illustrate how essential they are to Guyana’s history and its migration stories. These women, some of whom were born as early as the 1930s, have witnessed Guyana evolve from a colonized British territory to an independent state to a nation struggling to carve out its identity on the world stage to a country now burdened by its citizens departing. They have also been the ones most impacted by the last decade’s serious economic downturns in which the decline of mining industries, coupled with very little access to education beyond primary school, have left these communities with few or no choices to thrive. These elder Amerindian women are mothers, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers whose descendants have migrated to border countries like Venezuela and Brazil in South America, to North America, and to nearby Caribbean islands. And these women have made the choice to stay. While their children go back and forth between Guyana and their newfound lands, many of these elders have never left Guyana. Some have never left the villages where they were born. Some have no desire to leave. They implore us to ask, What does it mean to love a place? What is our accountability to place? I, wearing my hat as curator, editor, daughter of Guyana, immigrant, pored over the stories of these Guyanese women. What became clear was that the stories and photographs are declarations that these women will not disappear into history. Their stories underscore that, with ancestors and descendants long gone, the women and girls who remain in Guyana bear witness to the personal damage and the larger political consequences of a citizenry leaving its country. As migration swirls around us, we acknowledge leaving and being left as the great tension that twists our lives.

Those Who Remain: Portraits of Guyana’s Amerindian Women

by Khadija Benn

Guyanese have long experienced family separations through transnational migration mainly to bordering countries in the Caribbean, North America, and the United Kingdom. Labor migration has been a key driver of outward movement from Guyana. Its effects are particularly evident in indigenous communities as Amerindians transition to new countries in pursuit of gainful employment. Yet many family members often remain in Guyana. The seldom explored stories of indigenous people who choose not to migrate offer valuable insights into their notions of propinquity.

I encountered the women—the maternal elders of their families—featured in this photo essay while conducting research on social vulnerability in Guyana’s interior. As a geographer, my work involves settlement mapping and community-level assessments, and photography helps inform this practice. In our conversations on their lived experiences at the villages, the women recalled family members who resettled in other countries and shared how they stay connected, along with the difficulties of doing so. These dialogues surfaced their unique perceptions of time and space and revealed that distance is largely viewed as a relative construct that is immaterial against their strong ancestral ties. For instance, many did not perceive relatives living in neighboring countries as having settled abroad as Amerindians have traditionally considered these international borders to be fluid.

Their stories convey concerns about how migration contributes to loss of traditional cultures, languages, and communal ways of life. They also convey how those threats are superseded by the dignity and resilience of those who remain. These intimate portraits underscore Guyana’s rich Amerindian narrative and emphasize the role of matriarchs in shaping the lives of the next generation, regardless of where they end up, sustained by their heritage, traditional values, and work ethic and anchored by a profound connection with their lands.

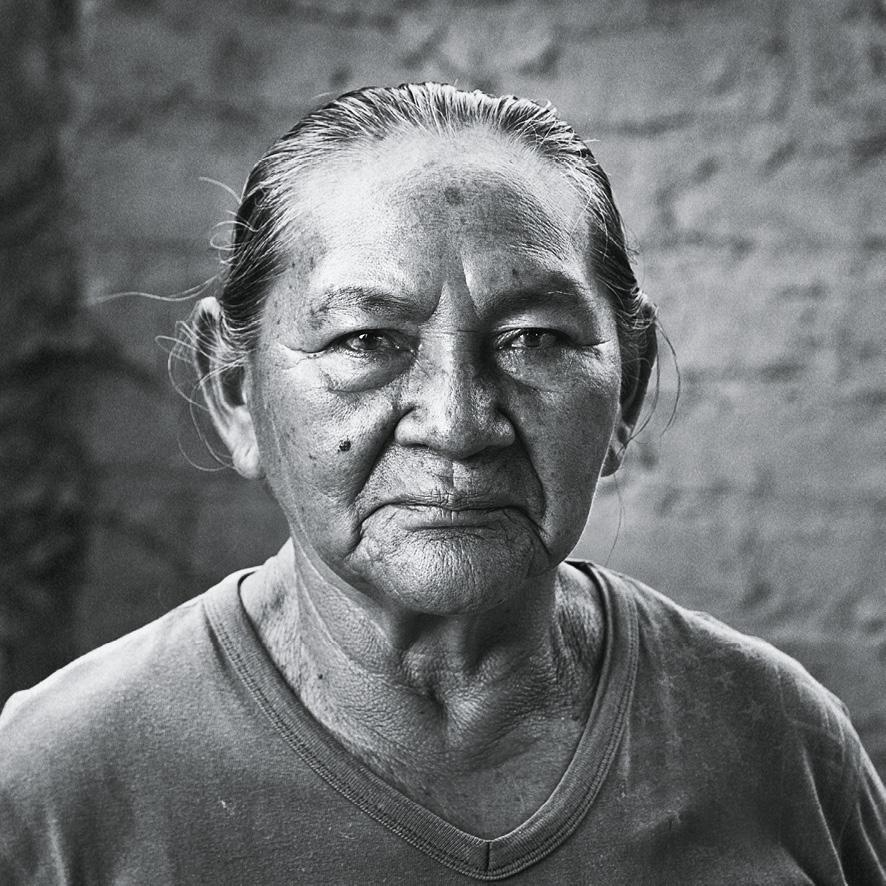

‘Even though so many of them gone, this is my country . . .

I couldn’t be happier being home in Guyana.’

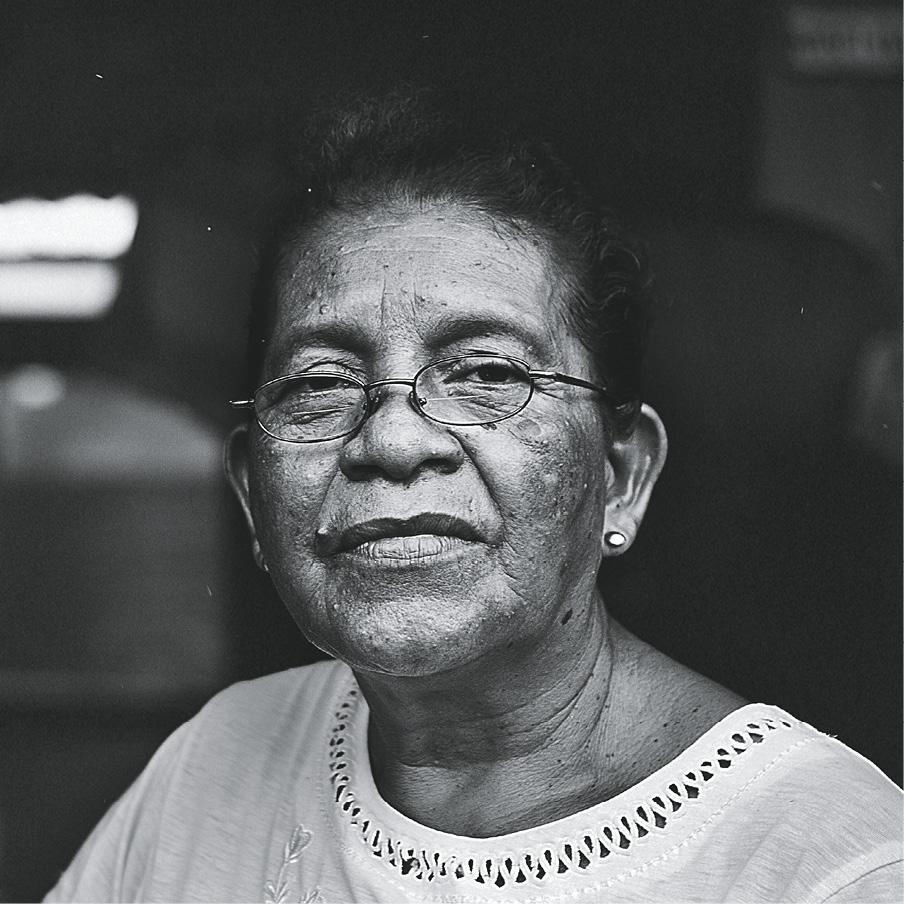

Lethem, Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo (Region Nine), Guyana. Khadija Benn, ‘Anastacia Winters’, from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017, digital photography.

© Khadija Benn. Courtesy of the artist. CC BY-NC-ND.

Anastacia Winters was born in the Wapichan village of Maruranau and eventually settled in Lethem, the Region’s administrative center, in the 1970s. She worked at the Lethem Hospital for many years while caring for her six children. Today, several of her relatives—two sisters, a niece, a son, and a stepson—live in the neighboring Brazilian settlements of Bon Fim and Boa Vista. Anastacia explained that their decision to migrate was based on the need to access wider employment prospects than what were available in Guyana at the time. Occasionally her relatives visit home, and she sees them often when she travels to Brazil. Another niece who has resided in the United States for more than twenty-five years dutifully calls home every week. Despite the throes of migration, Anastacia’s family has managed to remain close, which she attributes to the strong familial values sustained by her tribe.

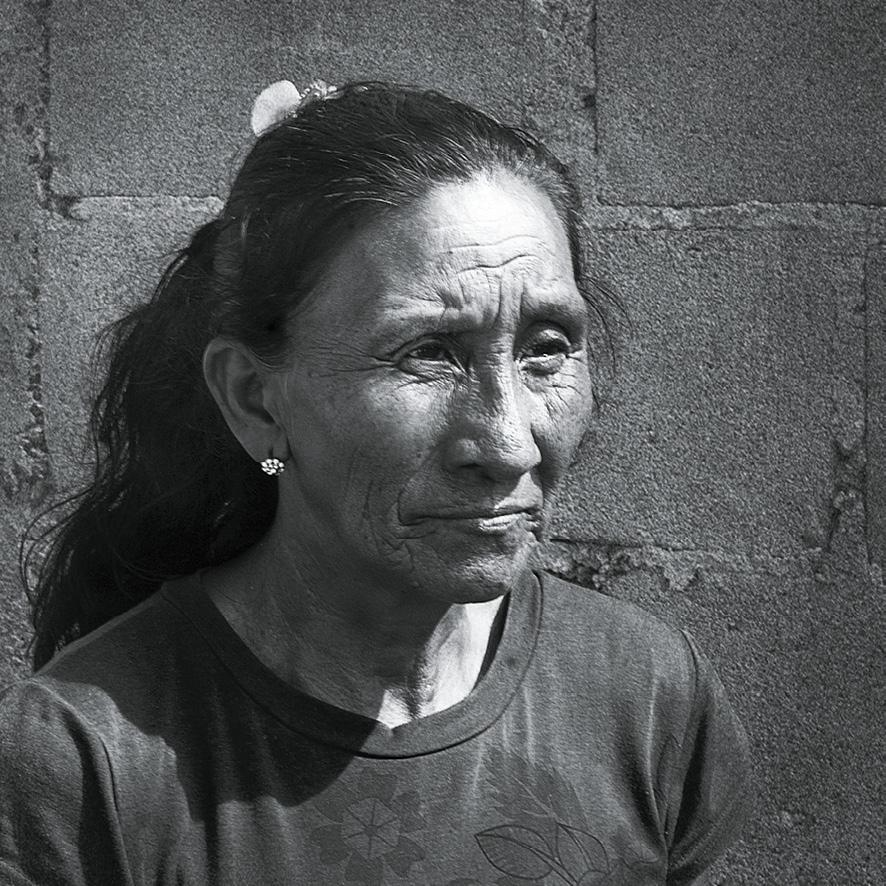

‘Everybody is here, my children, my grandchildren . . . this is where I belong.’

Tabatinga, Lethem, Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo (Region Nine), Guyana. Khadija Benn, ‘Mickilina Simon’, from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017, digital photography.

© Khadija Benn. Courtesy of the artist. CC BY-NC-ND.

Mickilina Simon was born in Sand Creek Village, a Wapichan settlement in central Rupununi, where, for many years, she planted crops such as cassava, banana, pineapples, and sugar cane to sustain her family. Mickilina now lives in Lethem with her son and granddaughter, having moved there many years ago to help raise her grandchildren. Her six children all live in Guyana. She has one close niece who migrated to Brazil in the late 1990s. She and the niece have maintained a close relationship over the years, talking regularly on the phone and visiting each other for weeks at a time. Mickilina says she was never interested in moving to north Brazil despite spending considerable time there and experiencing firsthand a more modern way of life. While learning the Portuguese language is a key deterring factor for her—she is fluent in both English and Wapichana—Mickilina asserts that she prefers the slower, simpler pace in her corner of Guyana.

‘I tell people that I born and grow in Guyana, and I will die in Guyana. I like to walk; I like to be free.’

Toka, North Rupununi, Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo (Region Nine), Guyana. Khadija Benn, ‘Lillian Singh’, from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017, digital photography.

© Khadija Benn. Courtesy of the artist. CC BY-NC-ND.

Lillian Singh spent her entire life in Toka, a quiet Macushi village in the upper Rupununi Savannahs. She lives there with her mother, husband, and two youngest children. She farms peanuts, corn, and bitter cassava. As is characteristic of Amerindian families, Lillian is close with extended family members. When she was eight years old, her aunt migrated to nearby Venezuela and her great-uncle moved to Brazil. They often visited Toka, but age now prevents them from traveling. These days, Lillian makes the occasional trip across the borders to spend time with them. In 2000, one of her older sons migrated to Boa Vista where he found work as a vaquero on a cattle ranch. Eventually he moved deeper into Brazil with his two children after his wife passed away. When we spoke, Lillian explained that she lost touch with them after that move as her village did not have telecommunication services in those days. She hasn’t heard from them in many years but remains hopeful that someday they will be able to reconnect.

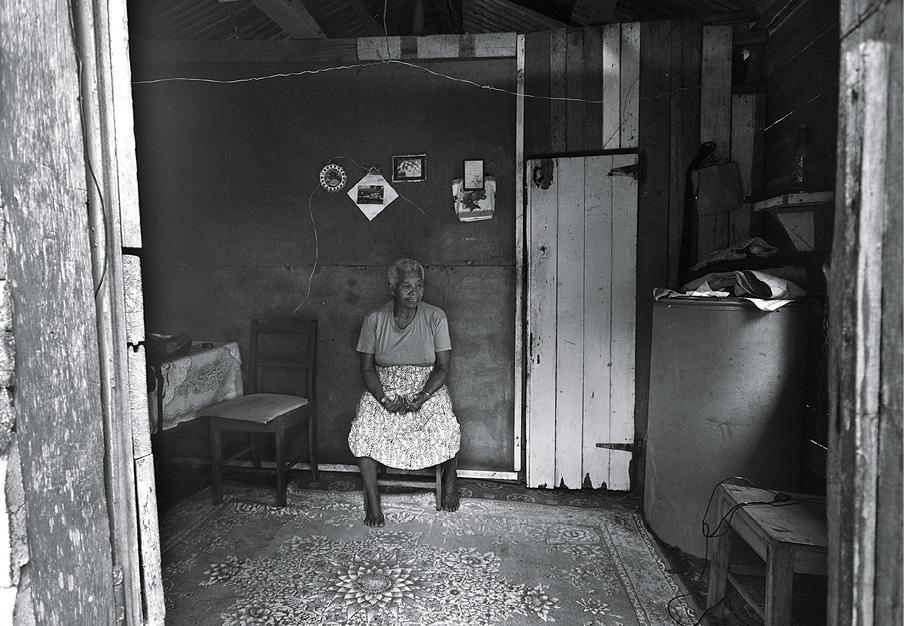

Almond Beach, Barima-Waini (Region One), Guyana. Khadija Benn, ‘Violet James’, from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017, digital photography.

© Khadija Benn. Courtesy of the artist. CC BY-NC-ND.

Violet James settled in Almond Beach in the 1980s when her husband undertook work as a sea turtle warden and conservationist. The small Almond Beach community sits at the northernmost point of the Shell Beach Protected Area, a 145-kilometer stretch of coastland that is a vital nesting ground for four endangered marine turtle species. Of Violet’s seven children, three live abroad. A son and daughter live in the United States, and another daughter lives in Venezuela. Limited telecommunications at the remote Shell Beach location challenge Violet’s ability to keep in touch with her children. She has heard from her daughter less in recent years as the situation worsened in Venezuela. She is proud that some of her children have had the opportunity to leave Guyana but wishes she could speak with them more. Violet expressed that even though migration places so much time and distance between them and she does not expect to see them regularly in the future, she will continue to remain close with her children.

© Khadija Benn. Courtesy of the artist. CC BY-NC-ND.

© Khadija Benn. Courtesy of the artist. CC BY-NC-ND.

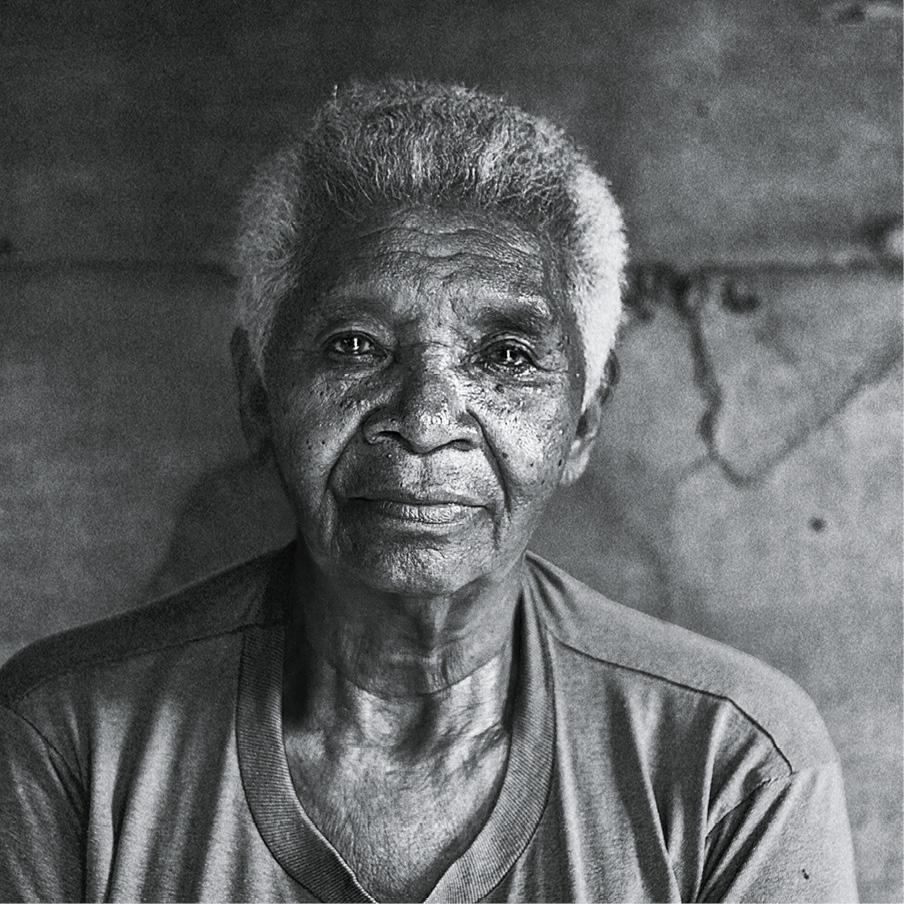

Mabaruma, Barima-Waini (Region One), Guyana. Khadija Benn, ‘Lucille Beaton’, from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017, digital photography.

© Khadija Benn. Courtesy of the artist. CC BY-NC-ND.

Lucille Beaton grew up at the Barama River mouth and eventually settled in Mabaruma, the northernmost town in Guyana. She spent most of her life fishing, farming, and raising her eight children. Most of her children still reside in Guyana, but she rarely sees them as their relationships have become strained over the years. Her closest bond is with one son who has lived in Canada for most of his adult life. Lucille was overjoyed when he had the opportunity many years ago to leave Guyana and make a better life for himself. Since leaving, he has only visited home twice. She no longer remembers how much time has passed since he moved away, but she still misses him daily. He continues to support her and they share regular phone calls. Alone in her simple wooden home, Lucille says she was never inclined to leave Guyana. She now occupies her days with activities for her church, where she has found solace and a deep sense of community.

Mabaruma, Barima-Waini (Region One), Guyana. Khadija Benn, ‘Agnes Phang’, from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017, digital photography.

© Khadija Benn. Courtesy of the artist. CC BY-NC-ND.

Agnes Phang was born in Mabaruma and has lived much of her life there. As a mother of fourteen children, her earlier days were spent subsistence farming and caring for her children. Many of them went on to raise their own families, some doing so farther away than others. Agnes explained that one of her daughters migrated to Venezuela more than thirty years ago. She has visited her daughter’s home a few times, but her grandchildren have never visited Guyana and she is unable to converse with them as they grew up speaking Spanish. Agnes also has a sister living in England with whom she maintains a fond relationship. Agnes has traveled to England several times to visit her, and her sister returns to Mabaruma about once a year to visit relatives and maintain the family property. Agnes says her travels to visit with family have allowed her to experience many interesting places, but she loves her home in Mabaruma above all.

‘I never want to live anywhere else . . . but it would be nice to see how [my children] living now.’

Mabaruma, Barima-Waini (Region One), Guyana. Khadija Benn, ‘Yvonne Gomes’, from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017, digital photography.

© Khadija Benn. Courtesy of the artist. CC BY-NC-ND.

Yvonne Gomes grew up in Morawhanna, which was once a vibrant fishing and farming village situated near the Barima estuary. In the late 1980s, frequent floods from increased tidal events forced her family to relocate to nearby Mabaruma where she had attended primary school as a child. Thirty years on, Yvonne is a farmer, tailor, and mother to eleven children. Over time her family unit grew smaller as some children went in search of greener pastures. More than ten years have passed since one of her daughters left Guyana to work in Barbados and three sons migrated to work in Canada, Venezuela, and Suriname. Yvonne understood they needed to leave to secure better jobs, but she says it was hard to watch them go. As they are seldom able to travel home, the family now relies on telephones to stay in touch. Yvonne is open to traveling someday to visit her family members, but, as echoed by other women in this narrative, she knows no other home and is content to spend her remaining years in Guyana.

Works Cited

Benn, Khadija. Anastacia Winters (b. 1947) from the series “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women.” Digital photograph. 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Benn, Khadija. Mickilina Simon (b. 1938) from the series “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerinidian Women.” Digital photography. 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Benn, Khadija. Lillian Singh (b. 1962) from the series “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerinidian Women.” Digital photography. 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Benn, Khadija. Violet James (b. 1952) from the series “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerinidian Women.” Digital photography. 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Benn, Khadija. Violet James sifts rice from the series “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerinidian Women.” Digital photography. 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Benn, Khadija. Lucille Beaton glances at the barrel sent by her son from the series “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerinidian Women.” Digital photography. 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Benn, Khadija. Lucille Beaton (b. 1937) from the series “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerinidian Women.” Digital photography. 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Benn, Khadija. Agnes Phang (b. 1940) from the series “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerinidian Women.” Digital photography. 2017. Courtesy of the artist. Benn, Khadija. Yvonne Gomes (b. 1957) from the series “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerinidian Women.” Digital photography. 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

- Khadija Benn, “Those Who Remain: Portraits of Guyana’s Amerindian Women,” in Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora, ed. Grace Aneiza Ali (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2020), pp. 91-108. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0218.08.[↑]