Time and Testimonial Address

In light of this pervasive normalization of AIDS, what significance and relevance do the films and videos of alternative AIDS media from the 1980s and ’90s now hold? Have their possible functions or effectiveness changed in the time since the historical context of their production and initial circulation? What are we to make of the fact that many of these works are now being institutionally preserved in the material archive? The motivation for archival preservation derives from the realization that the object’s “time” has passed, that it is in need of salvage in the face of possible destruction or oblivion. But what is actually being salvaged in such preservation and for what purpose?

As one of the major practices of AIDS cultural activism, alternative AIDS media produced an extraordinary body of films and videos during the first two decades of the AIDS pandemic. These films and videos worked to articulate both the exigency of the present moment of the pandemic and the historicity of the event, as well as the experience of those affected by it. They bear witness to AIDS through two necessary and simultaneous operations – contesting the dominant representation of AIDS and attesting to the experience of people living with AIDS in the midst of this trauma. Conceived in frameworks that exploit the inter-subjective possibilities of film and video media, these works engendered acts of bearing witness both at the level of production and reception. The AIDS activists, people with AIDS, and mediamakers who were involved in the production of these works, both in front of the camera and behind it, were afforded a medium through which they could bear witness to their experience of AIDS. For gay men, the simultaneously individual and collective trauma of AIDS has forged powerful psychological and political imperatives to bear witness, for which film and video production has provided a particularly effective set of opportunities. AIDS video activists have often commented that their practices were as much about empowering themselves through media production as transforming the consciousness or opinions of others.

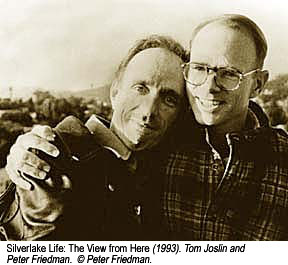

Regarding their reception, the address to an other inscribed in these films and videos potentially served two significant functions. The first was to bear witness within one’s community, to address other witnesses in the service of acknowledging the magnitude of the trauma and of sustaining community bonds. The second function was to bear witness to others outside the trauma of the epidemic, to produce new witnesses to it rather than mere spectators of it. It was an address rooted in a call for solidarity, to relate to the problems and suffering of people with AIDS as if they were one’s own, to share in the responsibility of addressing the social and political determinants of the AIDS crisis. The major problem for enacting this form of address arose from the difficulty many films and videos encountered in accessing viable distribution opportunities outside counter-public spheres. Works with a less politically defined address, such as Silverlake Life: The View from Here (Tom Joslin and Peter Friedman, 1993), were able to access a public television audience in the U.S., while activist video productions like Voices from the Front (Testing the Limits, 1991) were shut out of such distribution. Although the former video generated an impressive public response to its address from its PBS audience, we cannot know what the public response from that same audience would have been to the latter video’s address. However, one of the most effective venues for the enactment of this form of address has been the university classroom. The production of alternative AIDS media coincided with the institutionalization of lesbian and gay studies within the academe, allowing academics to teach classes that could incorporate such media. While alternative AIDS media has now virtually disappeared from the spaces in which it regularly screened in the 1980s and 1990s – galleries, lesbian and gay film festivals, public access television, and community organizations – it has retained a modest presence within college curricula, although often relegated to the category of media history.

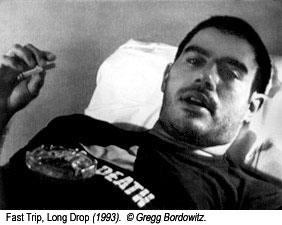

Are we thus now to regard this body of work as only a chapter in the history of alternative media or the history of the AIDS pandemic? To what might these works now bear witness in our “normalized” present? Despite substantial improvements in the lives of the seropositive and people with AIDS, so many people, particularly gay men, are still dealing with the trauma of multiple loss. Thus many works of alternative AIDS media continue to resonate with the needs of the present, to bear witness to unspeakable loss and alienation. It is not only works originally conceived as projects of mourning which now serve such a function. At one point in Gregg Bordowitz’s Fast Trip, Long Drop (1993), Jean Carlomusto comments how activist footage from the heyday of ACT UP has now also become a record of loss. What was once so energizing and empowering has become difficult for her to watch, almost a burden. Time has rendered militancy into mourning.