Unfashionable Memories

When I attended several screenings of AIDS activist videos at the Guggenheim Museum, New York City, in December 2000, I was struck by a bitter irony framing the context in which the work was being shown. Arriving early, as I always do at special screenings, I momentarily experienced that familiar rush of anxiety whenever I see a throng of people in the foyer – the tickets have all gone and I have lost my chance to see the work! Waiting in line, it quickly became apparent to me that my concern was completely unfounded. Wrapped up in their expensive winter wear and completely oblivious to the screenings, the people around me were all trying to get into the blockbuster exhibition on Giorgio Armani.

In the relatively small audiences of the screenings I attended, I recognized mostly the familiar faces of the downtown independent queer media scene, the regulars for such film and video programs. While this small community of viewers tucked away in the museum’s basement worked through our memories of a difficult, but in many ways more empowering, historical moment, the crowds upstairs were enjoying a hugely popular show celebrating a designer’s fashion that epitomized the conspicuous consumption of the Reagan-Bush era. These bourgeois museum-goers unwittingly replicated the national disinterest in the experience of people with AIDS during the 1980s, which had exacerbated both the spread of the pandemic and its traumatic effect on those affected.

Even amongst the queer media scene, the fatigue over the epidemic is apparent. At the Persistence of Vision Conference in San Francisco in 2001, which was organized to assess the state of contemporary queer media, the single panel dedicated to AIDS media suffered the indignity of panelists outnumbering audience members. While everyone else was contemplating the exciting developments in transgender and digital media, the small group of us in the room worked to analyze the reasons behind the panel’s patent “unfashionability.”

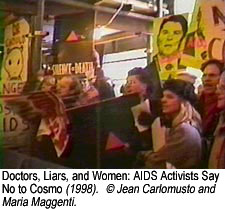

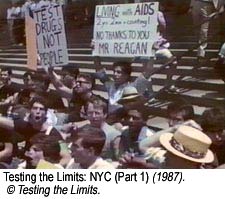

The Guggenheim screenings constituted a nine-part program entitled “Fever in the Archive,” a broad selection of works from the Royal S. Marks AIDS Activist Video Collection of the New York Public Library. The Collection resulted from an initiative in the late 1990s by the Estate Project for Artists with AIDS to preserve the grassroots response to the AIDS crisis by videomakers and activists in the United States. Funded by a number of non-profit and public grants, New York-based filmmaker and archivist Jim Hubbard undertook the principal research, collection, and cataloging of this AIDS activist media from around the country. The New York Public Library was chosen as the recipient of the collection in large part for its willingness to maintain public access to the works. “Fever in the Archive” demonstrated not only the very wide range of styles and forms employed by AIDS activist media, including music video, agit-prop montage, talking head testimony, and the video diary, but also the diverse functions served by such works, including HIV prevention, political mobilization, collective mourning, and media critique.

The historical moment that produced these films and videos is now clearly over. Their entry into the archive merely confirms this realization. To consider the questions of conservation or institutional preservation would remain a low priority at the time when these works were being produced. The exigency of that time required their urgent distribution and circulation. Now, in our different historical moment, what has become urgent is the need to preserve these films and videos, to save them from destruction, deterioration, and oblivion. The Estate Project for Artists with AIDS, a grant-funded nonprofit organization, oversees much of this preservation work. Founded in 1991 to assist visual artists with AIDS organize their estate and the disposition of their work, the Project has since expanded to include all of the visual and performing arts, including film and video. Furthermore, the Project has increasingly become more involved in organizing funding for specific preservation projects. Its major accomplishments with regards to the moving image have been the development of the Marks Collection of activist video and the preservation of works by David Wojnarowicz, Jack Smith, Warren Sonbert, and Jack Waters.

As with all moving image preservation, this work involves a fragile body of material, yet the task is complicated by the endangered bodies of many of those who produced these films and videos. Artists and mediamakers with AIDS have often not had the time, resources, or energy to deal with the future survival of their own work; their priorities usually remain elsewhere. Moreover, gay men continue to live and die in legal frameworks which deny their social and intimate bonds, thus frequently causing substantial difficulties in the preservation of work after the artist or maker has died. The drive to bring these works into the institutional archive emanates from the desire to ensure a form of textual survival, a means to keep their address open beyond death and beyond the initial historical moment in which it was formed.