The Bottom of Power

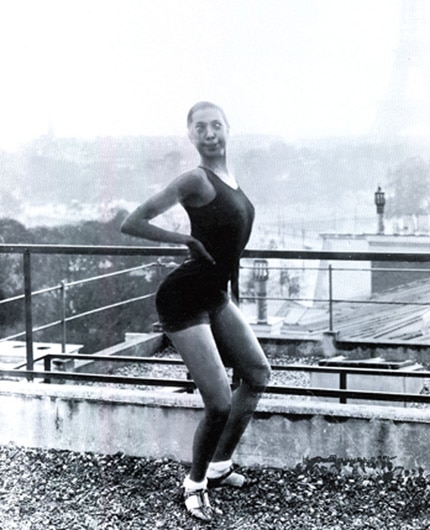

What kind of multiple meanings does this thespian-inspired, titillating piece of dialogue possibly suggest? Must 6 hit rock bottom? Must she create a critical foundation in her life and art with a bottom on which to stand firm? Or must she perhaps find a way to (re)possess the eroticism that her bottom represents? Must she discover a means to avoiding the invisibility of no-bodiness somehow? To escape the bottomless pit of sexual commodification, the film suggests that Girl 6 must follow the path of Josephine Baker. She must turn the site of (un)covering into her own fiction. She must, as Baker would famously proclaim, exploit “the intelligence of [her] own body” for her own purposes.

The bottom is where I want to begin today and it is, I suggest, one of several sites where the “intelligence” of Baker’s performance aesthetic lies. It is the bottom that links Baker not only to the words of 6’s acting instructor, but of course to Sara Baartman, the “Venus Hottentot,” a woman whose buttocks and genitalia were dissected and displayed at the hands of European science and whom Parks surely had in mind as well when she imagined her heroine’s dilemma. 1

Baartman’s sexual exploitation, as Mae Henderson has shown, set a precedent for the kind of ethnographic spectacle that Baker would have to navigate in the primitivist frenzy of 1920s Parisian music hall culture. However, as Henderson makes clear, whereas Baartman functioned as “pure display … an icon of black sexuality and the (black) female sexual grotesque,” Baker, removed by a century from Baartman, was able to turn the static body of black female sexual exploitation into a dynamic, mobile enterprise. 2

I want to think in particular about Henderson’s important claim that Baker was “a seasoned comedienne” who “combined a performance of the erotic with elements of the parodic” (124). I want to walk through some of the specific modes of comedy that Baker stylized and perfected—moves that highlight her corporeal elasticity and underscore the ways in which Baker and other black female entertainers utilized comic insurgency to wrest their bodies from socio-historical conventions. Below, I suggest that we might ask what kinds of jokes Josephine Baker could tell with her body and whether the body is capable of lobbing a few punch lines.

In this regard, I would have us think more about this notion of the bottom as it literally and figuratively relates to Josephine Baker. Specifically, I am interested in the “place” of the bottom in black women’s comedic corporeal politics and the ways in which we might extend this concept of the bottom to refer not only to the physical body of the black woman but to other ends that reveal her innovative comedic strategies of gestures and corporeal eccentricities. Read from this perspective, we can consider the ways that Baker’s body perhaps re-oriented the spectacular attention directed at black female bodies in public spaces and potentially disabled the kind of exploitative spectatorship that circumscribed Sara Baartman.

As bell hooks has made clear about Baker’s body, “one can hardly overemphasize the importance of her rear end.” Baker herself reportedly argued that the “rear end exists … I see no reason to be ashamed of it.” Hooks thus contends that with “Baker’s triumph, the erotic gaze of a nation moved downward: she had uncovered a new region for desire.” 3

But we might move from this physical region of “plenty” to consider its metaphorical dimensions. Perhaps, when we think about Josephine Baker, we’re dealing not just with the triumph of a physical black bottom on display, but with other kinds of ends and posterior spaces as well. Baker was all about the end, I would argue, but her genius surfaced most brilliantly in choreographic tales/tails that exceeded the frame of her body.

If we think, for instance, of these alternative endings as spaces that yield the kind of gestures that Carla Peterson terms “eccentric”—”an empowering oddness” and “a notion of off-centeredness” that suggests “freedom of movement” for black female performers, 4 we might move then from ends to Josephine Baker’s eccentric means so as to interrogate the specific gestures that she utilizes to disable, to disrupt, and to deflect more limited regimes of looking.

- Sander L. Gilman, “Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and Literature,” ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. “‘Race,’ Writing and Difference (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 223-61. Anne Fausto-Sterling, “The Comparative Anatomy of ‘Hottentot’ Women in Europe, 1815-1817,” eds. Jennifer Terry and Jaqueline Urla, Deviant Bodies: Critical Perspectives on Difference in Science and Popular Culture (Bloomington, Indiana UP, 1995), 19-48. Janell Hobson, Venus in the Dark: Blackness and Beauty in Popular Culture (New York: Routledge, 2005).[↑]

- Mae G. Henderson, “Josephine Baker and La Revue Nègre: From Ethnography to Performance,” Text and Performance Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 2 (April 2003): 127. All future references to this text will be made parenthetically unless otherwise noted.[↑]

- bell hooks as quoted in Michael Borshuk, “An Intelligence of the Body: Disruptive Parody Through Dance in the Early Performances of Josephine Baker,” eds. Dorothea Fischer-Hornung and Alison D. Goeller. EmBODYing Liberation: The Black Body in American Dance, Forecaast (Forum for European Contributions to African American Studies), Volume 4: 53.[↑]

- Carla Peterson, “Foreword: Eccentric Bodies,” eds. Michael Bennett and Vanessa Dickerson, Recovering the Black Female Body: Self Representations by African American Women (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2001), ix-xvi.[↑]