Gender on Ice Revisited

Gender on Ice was the first critical book in the U.S. on both north and south polar exploration narratives that re-engaged the legacy of the Heroic Age (1895-1914) of Arctic and Antarctic exploration. It articulated a highly critical, revisionist attitude toward explorers and their writings in its emphasis on examining which narratives, lives and sacrifices counted and which did not. It is significant that the book puts emphasis on visual culture and specifically evaluates these heroic narratives through the way they were represented in National Geographic magazine, a new publication of visual culture that linked itself to a national image of the United States in the 1890s and seized the poles as a metaphor for modernity and progress. Gender on Ice also offered a revisionist account of white explorers such as Robert Peary and Captain Robert Falcon Scott, who were deemed heroes of their national cultures in the early part of the 20th century, in spite of the evidence that they led failed expeditions. Both Scott and Peary fabricated the events of their expeditions to suit the particular imperial and masculinist ideologies that each characterized. The book also highlighted the exclusion of Matthew Henson, the black American explorer who accompanied Robert Peary in his trek to reach the North Pole, and the ways he was not given equal credit for his central place in the story as it was told by Peary and interested institutions such as National Geographic magazine. Gender on Ice discussed how the Inuit men and women helpers, companions, and guides were erased in their role as travelers and explorers because of their perceived “primitive” status. Thus, the book helped document the ways that polar exploration had not always been the exclusive preserve of “white” male explorers. By showing alternative narratives of polar exploration “told” in the words and lives of native, non-western, and female subjects, the study challenged the dominant historical discourse of travel in which white western men figured as the sole aesthetic interpreters or scientific authorities.

University of Minnesota Press, 1993

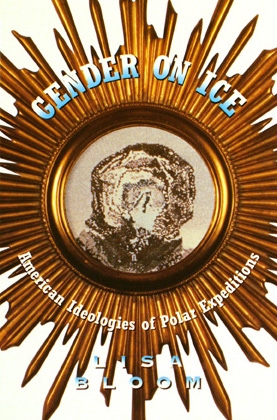

Cover Illustration by Narelle Jubelin, Cover Design by Brad Norr

Though the book was about gender and its connection to nationhood and the politics of imperialism and science, much of the interest generated by Gender on Ice stemmed from how the book was written, and how the writing style of the book played off the epic quality of these male heroic narratives set in regions that overwhelm the senses with their dangerous weather, extreme cold, blinding light and whiteness. The playfulness of the book was announced by its cover, which uses artwork by the Australian artist Narelle Jubelin to foreground the book’s anti-heroic emphasis (see Figure 1). The image is a close-up in petit point, or needlepoint stitch, of the face of a polar explorer that is disintegrating. This disturbing image is placed within a bombastic gilt frame to explicitly underline the book’s overriding thesis: how the traumatic experience of failure in both the British and American expeditions was reworked to turn the official version of events into something worthy of public reverence. 1

Gender on Ice was a case study, rather than a highly theoretical work, that at the time tried to break new ground by bringing colonial discourses of exploration, science, and adventure not only under the consideration of gender studies, but into conversation with cultural studies of race and ethnicity. In this project, the parameters of gender studies were stretched to include its historically “other” subjects, marking a shift in then current feminist practice. Thus, Gender on Ice was not a book about women per se—though the history I tell does bear directly upon the condition of women and relations of gendered power during this period—but a feminist critique of a gendered concept of heroism associated with the new importance given to turn of the century polar exploration as a source of national virility and toughness. By asking, somewhat ironically, what types of white men the Arctic and Antarctic make, the book analyzes how reaching the North Pole and the South Pole functioned as a testing ground of masculinity, where there was shame attached to losing, and thus failure to demonstrate manhood.

The denial of failure at each pole by both the British and the Americans establishes a continuity between two national events. I focus on the tragedy of the failed British polar expeditions of Captain Robert Falcon Scott to provide important contrasts and parallels with U.S. polar exploration narratives. I explain how Peary’s very American scientific enterprise, which stresses tangible results, contrasts with Scott’s account, which also understood the expedition as making contributions to science, but which followed British literary and military traditions valorizing the inner qualities of tragic self-sacrifice rather than performance and achievement. Drawing on the letters and diaries of those members of Scott’s expedition who were denied power by their social position, I examine how Antarctica becomes a discursive space. Here a nationalist myth was established in which writing itself becomes a means to mythologize an ideology of British white masculinity while, paradoxically, the male body is ignored. Thus, in the Scott narrative, examples of the men sleeping in tents or on a ship together, emphasizing the closeness of their gendered, physical bodies, are ignored and replaced by moral character. Scott claims that he exposed himself and his men to additional dangers and personal sacrifices, and connects his actions to a higher national mission as defined by the metaphor of tragic self-sacrifice, providing the foundation on which a kind of white heteronormative masculinity becomes heroicized.

In contrast to the British, the Americans try to produce a narrative of masculinity that is part of a scientific tradition worked discursively to erase the significant presence of Inuit women, men and the participation of Matthew Henson. There is a larger emphasis on exteriority, where successful performance and achievement matter most. While the tragedy of Scott’s failed expedition to the South Pole is acceptable within the parameters of the literary, there is no place for failure within the ideological narrative of scientific progress that framed the discourses of the Peary expedition. 2 As a result, Peary’s achievement was never scientifically disputed. 3 This inability to acknowledge outright the failure of the Peary expedition, I argue, explains why the critique of Peary remained narrowly focused on establishing or disputing the accuracy of Peary’s claim to the North Pole and did not resonate more widely as in the case with Scott’s expedition. 4

These questions, in the context of my book, are meaningful in terms of the unacknowledged failure enacted not only at the North Pole at the early part of the 20th century, but also in the later part of the century during the Vietnam war and at the time of the book’s writing, the first Persian Gulf War. Gender on Ice has been my attempt to explain the interconnections between the multiple narratives of national identity, scientific progress, modernity and masculinity across the national cultures of the United States and the United Kingdom. In what follows, I will return to how these discourses are invoked and re-narrativized in the work of Isaac Julien and Connie Samaras.

- The British lost the race to the South Pole to Roald Amundsen of Norway who reached the pole in 1911, one month ahead of Captain Robert Falcon Scott. Scott and his team of four men died of hunger and cold on their way back. After completing nearly seven-eighths of the distance they encountered a blizzard and, unable to reach their food depot just 11 miles away, died in their tent from a combination of frostbite, sickness, and starvation. Whereas Scott’s narrative of failure was straightforward, Robert Edwin Peary’s claim to have been the first person, on April 6, 1909, to reach the geographic North Pole—a claim that subsequently attracted much criticism and controversy—is today widely doubted for a number of reasons and remains the focus of controversy.[↑]

- See Lisa Bloom, Gender on Ice, 127-129.[↑]

- In the end, there was enough of a doubt about his claims that he was recognized by a congressional committee as “attainer” of the pole not “discoverer” and given a Rear Admiral’s pension by a special act of Congress in 1911.[↑]

- See Lisa Bloom, Gender on Ice, 130-131.[↑]