Readings of Josephine Baker’s cultural status in the twenties underscore but also tend to limit her stylized performance of the black body as a modern, primitivist fetish within the registers of colonial fantasy. For Harlem Renaissance artists such as Gwendolyn Bennett, Baker’s mimicry of primitivist codes, mixed with her mastery of Parisian cosmopolitanism, was an empowering role model in her own moment. Baker’s performance, of course, would lead her to become a utopian symbol of progressive celebrity for diverse audiences throughout Europe, South America, and eventually in the United States, especially in the 1950s, when Baker was a civil rights pioneer in league with Walter White and the NAACP. 1 But from the beginning, the force of Baker’s performance had its source in a psychic register exceeding that of colonial fantasy. Not just an exotic object or an imaginary bearer of the European onlooker’s desire, Baker emerges as agent, paradoxically enough, by way of an encounter with a more radically inaugural gaze, one that finds its source in what Jacques Lacan theorizes in Seminar XI as the traumatic Real.

To begin with, in her 1923 poem “Heritage,” Gwendolyn Bennett expressed the desire for an African American heritage in the stylized landscapes of modernist primitivism that would similarly shape the staging of La Revue Nègre two years later:

I want to see the slim palm-trees,

Pulling at the clouds

With little pointed fingers….I want to see lithe Negro girls

Etched dark against the sky

While sunset lingers.I want to hear the silent sands,

Singing to the moon

Before the Sphinx-still face….I want to hear the chanting

Around a heathen fire

Of a strange black race.I want to breathe the Lotus flow’r,

Sighing to the stars

With tendrils drinking at the Nile….I want to feel the surging

Of my sad people’s soul,

Hidden by a minstrel-smile. 2

Here, Bennett conjures Africa through anaphora in the repetition of the poet’s desire not just for the kind of stylized vision of exotic “palm-trees” derived, perhaps, from writer Claude McKay, but as a more holistic structure of feeling that involves the five senses. Bennett insists that she wants “to see lithe Negro girls /Etched dark against the sky,” and to “feel the surging /Of my sad people’s soul /Hidden by a minstrel smile.” Moreover, her allusions to the moon’s “Sphinx-still face” and “the Nile” advance the kind of cultural geography of African location witnessed, for example, in Langston Hughes’s celebration of “the Nile” in “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” as a body of water “ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.” 3 Before Countee Cullen’s own “Heritage” poem, Bennett imagines the subversive “chanting /Around a heathen fire /Of a strange black race.” Beyond such primitivist reminiscences, however, the poem is marked by a coded, and decidedly African American, literary “heritage.” Bennett’s “minstrel-smile” which hides “the surging /Of my sad people’s soul” communicates the same “double consciousness” portrayed in Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “We Wear the Mask.”

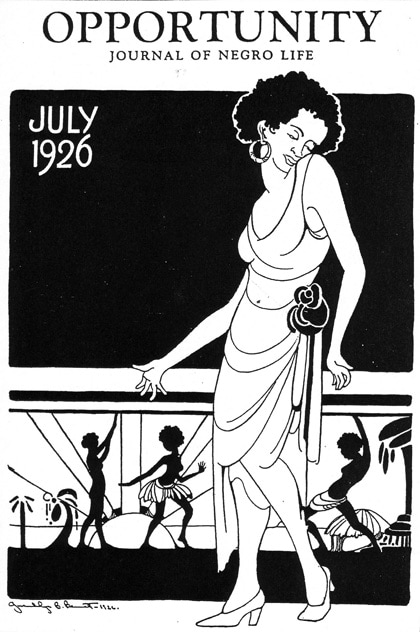

By 1926, Bennett’s aesthetic ideology had evolved from what Sterling Brown described as the New Negro “discovery of Africa as a source of race pride” to a more cosmopolitan mixing of primitive and modern aesthetic codes, such as in her cover illustration for Opportunity. This transition was directly linked to Bennett’s viewing of Josephine Baker’s celebrated dance sauvage in La Revue Nègre the preceding year. 4 In her visual art, Bennett presents the modern black dancer as a more ecstatic and self-possessed version of Baker’s cosmopolitan persona that signifies, even as it masks, a stylized primitivist self. The body language of the racially ambivalent figure silhouetted in white against a black background suggestively mimics the bold black celebrants modeled on the moves of Baker’s danse sauvage. Aesthetic primitivism, popularized in the avant-garde imagination of Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Apollinaire, Blaise Cendrars, and the Zurich dadaists Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara, coincided with the influx of African American jazz culture and the emergence, as James Clifford documents, “of a modern, fieldwork-oriented anthropology … at the Paris Institute of Ethnology and the renovated Trocadero museum.” 5 In critiquing the conjuncture of experimental modernism, primitivism, and ethnography, Clifford concludes, “the black body in Paris of the twenties was an ideological artifact” (Clifford 197). Following Clifford, Paul Gilroy also reads Baker as a modernist minstrel that performed the Eurocentric demand for “escapist exoticism.” 6

- Michel Fabre describes Josephine Baker as a “cultural beacon” whose artistry makes her a lasting lieu de mémoire. See “International Beacons of African-American Memory: Alexandre Dumas père, Henry O. Tanner, and Josephine Baker as Examples of Recognition,” History and Memory in African-American Culture, ed. Geneviève Fabre and Robert O’Meally (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 122-149.[↑]

- Gwendolyn B. Bennett, “Heritage,” in Shadowed Dreams: Women’s Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance, ed. Maureen Honey (New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1989), 103.[↑]

- Langston Hughes, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, ed. Arnold Rampersad (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 23.[↑]

- Sterling Brown, “Contemporary Negro Poetry 1914-1936,” An Introduction to Black Literature, ed. Lindsay Patterson (New York: Publishers Co., 1969), 146.[↑]

- See James Clifford, “Negrophilia: February, 1933,” A New History of French Literature, ed. Denis Hollier (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), 904. For a discussion of modern primitivism and Josephine Baker as a modern sauvage, see James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 197-200.[↑]

- Paul Gilroy, “‘To Be Real’: The Dissident Forms of Black Expressive Culture,” in Let’s Get It On: The Politics of Black Performance, ed. Catherine Ugwu (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995), 22.[↑]