Conceptualizing Feminist and Queer Afro-Asian Formations

We begin this issue with Tamara Bhalla writing on Du Bois’s Dark Princess, because she foregrounds the ability of queer and feminist Afro-Asian analysis to decenter hetero-patriarchal genealogies of cross-racial alliance. If Joseph warns us to be cautious about the ways that investments in political community can be uncritically romantic, Bhalla explores the radical political potential of romance. She focuses on the way that literary romance, a genre that a generation of postcolonial feminists argue was central to the emergence of literatures of empire, can be rerouted through the anti-imperialist imagination. In reading Du Bois’s novel against the grain of its Orientalist narrative, Bhalla argues that the novel’s romance is a structure of feeling that is not reducible to its paradigmatic story of heterosexual desire between the African American civil rights leader Matthew Townes and the Indian princess Kautilya. Rather, romance names a broader politics of fantasy and desire that finds its fullest expression in Du Bois’s real-life narrative of cross-racial brotherhood with Indian nationalist leader Lajpat Rai. Bhalla’s recuperative reading of Du Bois’s and Rai’s bromance asks us to rethink romance as a mode of political relationality that exists beyond heterosexual couplehood. At the same time, Bhalla observes the way that an Orientalized Asian femininity secures the novel’s heteroromantic narrative and Du Bois’s bromantic vision of cross-racial solidarity.

The rest of the contributors take up Bhalla’s call to decenter heteronormative and masculinist genealogies of cross-racial alliance within Indian Ocean and Black Atlantic diasporas. The contributors to this issue cover a broad range of spaces and subjects, spanning China, India, Iran, and South Africa, and topics from Mao’s political influence to the post-millennial pop culture of Beyoncé and Janelle Monáe. Together, they speak powerfully to the epistemic violence of the cleaving of blackness from brownness in dominant, heteronormative conceptualizations of nation and diaspora. They call for us to understand these racial formations as, instead, relational and mutually constitutive.

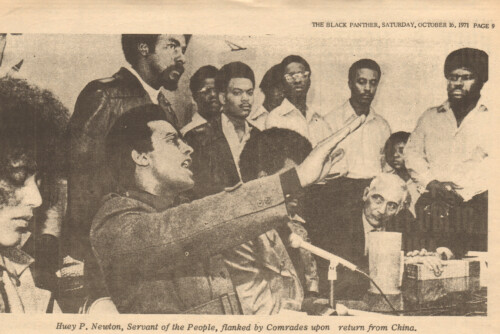

Building upon Bhalla’s revised critique of bromance, Mingwei Huang examines archival photographs of black and Asian political leaders in order to show how the staged quality of these images contributes to dominant narratives of Afro-Asian brotherhood. She focuses on the triangulated dynamic among Huey Newton, Richard Nixon, and Chairman Mao Tse-tung during the former leaders’ visit to China in 1971. By analyzing the “uninterrogated power” granted to the photos that document these political meetings, Huang presents a feminist analysis of the homosociality and gender performance that underwrote the self-representation of these community and national leaders. Deconstructing how the photos were carefully staged, Huang reframes photography not as historical document, but as performative spectacle. The staging of these photos, in turn, captures the precarious nature of Afro-Asian political solidarity, enacted as much for the benefit of each politician as for the sake of anti-capitalist revolution. In particular, Huang attends to the photographic absence of the women who attended these proceedings, like Elaine Brown, who would go on to chair the Black Panther Party after Newton. Refusing to turn a nostalgic lens to the Black Power movement, Huang shows how women were key players in facilitating the 1971 meetings among Mao, Newton, and Nixon, but orchestrated out of the frame of history.

Because popular cultural forms are often considered “too ‘apolitical,’ ‘feminized,’ or commodified for intellectual rehabilitation within studies of race and diaspora,” they remain critically neglected sites for exploring alternative forms of political relationality. 1 However, several contributors to this issue push against the dominant cultural dismissal of femininity and feminization by foregrounding distinctly feminine embodiments and feminized popular cultural forms – queer dance spaces, girl culture, and beauty – in conceiving of queer and feminist expressions of interconnectivity. In her article, Rebecca Kumar, for example, argues for a woman-centered reclaiming of Orientalism for Afro-Asian feminist politics. In doing so, her essay highlights the collective absence of black feminine-identified subjects across these articles and the need for more work that foregrounds black women and femmes as central to queer and feminist Afro-Asian formations. Kumar examines how expressions of black feminism in contemporary R&B performance draw from South Asian spiritual practices and figures such as yoga and Hindu goddesses in ways that allow black women to assert their roles in combating antiblack racism beyond that of their “gendered duty” to support black brotherhood. She argues that Janelle Monáe’s engagements with yoga and Beyoncé’s and Willow Smith’s self-portraitures as Hindu goddesses are both feminine and also feminist acts of cultural borrowing and anti-nationalist practices of South Asian culture. Kumar draws on Mullen’s concept of Afro-Orientalism and Helen Jun’s concept of black Orientalism to challenge the global popularity of yoga and South Asian fashions and music as a predominantly white, middle-class, neoliberal practices of self-transformation and enlightenment. What she calls “black goddess politics” provides a more politically robust framework for challenging racist representations and cultural practices, Indian nationalist articulations of a light-skinned Indian beauty ideal, and criminalized images of blackness.

Extending Kumar’s focus on pleasure and leisure as practices of Afro-Asian feminist possibility, Apryl Berney’s remarkable urban history, with which we opened this introduction, explores the creative friendship forged between mixed race Afro-Filipina artist Sugar Pie DeSanto and African American singer Etta James in San Francisco’s working-class Fillmore neighborhood. By exploring this musical collaboration, Berney considers how young women at home, church, and school “transformed domestic spaces from sites of containment to laboratories of social and cultural experimentation.” While respectability politics managed the mobility of African American, Filipina, and mixed-race teenage girls in public, Berney argues that these women found social outlets in basement and house parties, which fomented a lively “Afro-Asian working-class female youth culture.” These cross-racial domestic and leisure spaces allowed young women to bond over music, fashion, and dance – cultural practices that shaped their artistic careers and fostered the freedom to develop a sense of their own sexuality. Berney thus reveals how sexuality and gendered mobility formed both tensions and possibilities for cross-racial affiliation.

In his ethnography, Kareem Khubchandani moves us from young women’s homosocial space of basement house parties of postwar America to queer men’s spaces of gay nightlife in Bangalore, India. Sharing Kumar’s sensibility of critical appropriation, Khubchandani shows that gay Indian men’s appropriations of blackness, such as voguing, are neither recuperative nor inherently exploitative. Instead, they are expressions of the way that racial hierarchies invariably structure interracial queer desires and pleasures. In one sense, Khubchandani’s analysis of gay men’s desires for and fantasies about black gay masculinity might be understood as an explicitly eroticized form of Sexton’s notion of black affection, discussed earlier. Yet rather than operating in the service of racialized political (be)longing, as Sexton argues, the pleasure that gay Indian men take in the appropriation of black cultural forms and in erotic fantasies about black masculinity work to challenge state and cultural antiblack racisms that have escalated with more recent waves of African migration to India. These forms of pleasure and desire certainly rely on “racial and sexual fictions” about an aggressive black masculinity; but they also enable gay Indian men to draw upon performances of black femininity that are otherwise elided in constructions of a hegemonic global gay masculinity. For Khubchandani, black femme aesthetics like voguing and twerking allow for intimate exchanges between black and brown femmes that exist through gesture rather than bodily proximity. Thus, unlike more politically bankrupt performances of cultural appropriation and objectification that presume a white Western gaze, these performances of blackness and queerness insist upon a black spectator and even allow Indian men to care for their black lovers whose lives in the subcontinent are defined by persistent precarity and uncertainty as racialized queer migrant subjects.

The concluding essays in this issue turn to the visual register as an alternative archive of Afro-Asian alliance and community formation. In his photographic essay, Jordache Ellapen builds upon Khubchandani’s attention to the limitations of racial and sexual exceptionalisms in the constitution of the postcolonial nation-state, albeit inversely. He visualizes Indian migration to South Africa through queer brown male bodies that multiply disrupt dominant black nationalist histories of the post-apartheid nation. Deploying an aesthetic mode that he calls “transgressive erotics,” Ellapen superimposes personal family photographs onto historical photographs of Indian “pass” documents. These documents classify the race, gender, and marital status of migrant men and were issued by the colonial South African state beginning in the nineteenth century. Focusing on the bodily proximities between Indian men and the appearance of a mixed-race ancestor among the family photographs, Ellapen visualizes queer male and interracial intimacies as part of the colonial history of the apartheid state. These transgressive erotics allow us to see how whiteness, blackness, and queerness “haunt the formation of Indian identity” in South Africa, despite both the state’s and the Indian migrant family’s insistence on racial discreteness and compulsory heterosexuality. Ultimately, Ellapen’s visual aesthetic of transgressive erotics asks us to think beyond a model of coalitional politics in which “black” and “Indian” remain discrete racial categories and, instead, toward considerations about how the racial category “South Asian” gains resonance within various racial regimes of blackness.

Like Ellapen, Manijeh Nasrabadi speaks to the way that visual art globally reframes existing categories of Afro-Asian studies, in this case by linking West Asia with the African American diaspora. Nasrabadi analyzes the work of the queer feminist Iranian American artist Amitis Motavelli, who came of age in the United States during the 1980s, where she studied the civil rights movement as a student of Angela Davis. In particular, Nasrabadi examines Motavelli’s 2010 exhibit in Tehran, Here/There, Then/Now, in which she stitched Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee images onto Shia roseh flags and handwrote the Persian translation of Fannie Lou Hamer’s 1964 speech at the Democratic Party National Convention onto the window of the Aaran Gallery. Hamer’s speech drew attention to her experience with white supremacy, particularly its sexualized violence against black women. Motevalli presented Hamer’s speech and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee images of police repression as a lens through which exhibit audiences could reflect on and recognize the parallel violences used against Iranians who resisted the state. This comparison refuses to conflate U.S. civil rights and post-2009 Iran histories; instead, Nasrabadi highlights the similarities between the repressive practices of the United States and Iran, and the way state violence links imperial and anti-imperial sites across the globe. Her piece thus challenges post-9/11 American exceptionalism, which positions U.S. secularism as more liberated than religious societies of Muslim-majority countries like Iran, by “refram[ing] the U.S.-Iran conflict by engaging each national context as a site of ongoing battles for social justice.”

To conclude this issue, Crystal Parikh explores failed moments of interracial solidarity – those in which groups of color feel betrayed by one another, rather than aligned. Through her analysis, Parikh illustrates a comparative reading practice that seeks out moments of possibility rather than archival evidence of alliance. She draws on a curious reference to Columbus’s misidentification of America (as India) that appears in the pages of Ralph Ellison’s classic racial allegory, Invisible Man, and brings it into conversation with two Asian American films about the multiracial United States, Sa I Gu (1993) and The Betrayal (2008). She identifies these documentaries as capturing moments that detour Asian American subjects away from alliance, to either focus on state reparations or perpetuate racial divisions. An “ethics of betrayal” thus acknowledges the agency of Asian Americans to make choices other than alliances, granting them “the complex personhood that modern nationality avers.” Where minority subjects may not always choose solidarity as a survival strategy in the face of state repression, Parikh argues that a feminist and queer comparative analysis can foreground possibilities for Afro-Asian affiliation, and also acknowledges the ambiguity with which we face the Other. Indeed, one way to resist the utopian heteromasculinism we critique in this issue is to not end with a handshake between male leaders, as it were. Instead, we might remain open to the fractious and frictional relations that queer and feminist analyses illuminate as commensurate with convivial forms of political relationality. In her analysis, in other words, Parikh warns us against uncritically privileging solidarity as a prevailing framework for Afro-Asian formations.

- Vanita Reddy, Fashioning Diaspora: Beauty, Femininity and South Asian American Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2016), 29.[↑]