|

Lisa Bloom,

"Polar Fantasies and Aesthetics in the Work of Isaac Julien and Connie Samaras"

(page 2 of 6)

Gender on Ice Revisited

Gender on Ice was the first critical book in the U.S. on both

north and south polar exploration narratives that re-engaged the legacy

of the Heroic Age (1895-1914) of Arctic and Antarctic exploration. It

articulated a highly critical, revisionist attitude toward explorers and

their writings in its emphasis on examining which narratives, lives and

sacrifices counted and which did not. It is significant that the book

puts emphasis on visual culture and specifically evaluates these heroic

narratives through the way they were represented in National

Geographic magazine, a new publication of visual culture that linked

itself to a national image of the United States in the 1890s and seized

the poles as a metaphor for modernity and progress. Gender on

Ice also offered a revisionist account of white explorers such as

Robert Peary and Captain Robert Falcon Scott, who were deemed heroes of

their national cultures in the early part of the 20th century, in spite

of the evidence that they led failed expeditions. Both Scott and Peary

fabricated the events of their expeditions to suit the particular

imperial and masculinist ideologies that each characterized. The book

also highlighted the exclusion of Matthew Henson, the black American

explorer who accompanied Robert Peary in his trek to reach the North

Pole, and the ways he was not given equal credit for his central place

in the story as it was told by Peary and interested institutions such as

National Geographic magazine. Gender on Ice discussed how

the Inuit men and women helpers, companions, and guides were erased in

their role as travelers and explorers because of their perceived

"primitive" status. Thus, the book helped document the ways that polar

exploration had not always been the exclusive preserve of "white" male

explorers. By showing alternative narratives of polar exploration "told"

in the words and lives of native, non-western, and female subjects, the

study challenged the dominant historical discourse of travel in which

white western men figured as the sole aesthetic interpreters or

scientific authorities.

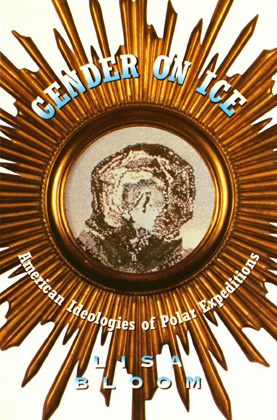

Figure 1 Cover of Gender on Ice: American Ideologies of Polar Expeditions

University of Minnesota Press, 1993

Cover Illustration by Narelle Jubelin, Cover Design by Brad Norr

Though the book was about gender and its connection to nationhood and

the politics of imperialism and science, much of the interest generated

by Gender on Ice stemmed from how the book was written, and how

the writing style of the book played off the epic quality of these male

heroic narratives set in regions that overwhelm the senses with their

dangerous weather, extreme cold, blinding light and whiteness. The

playfulness of the book was announced by its cover, which uses artwork

by the Australian artist Narelle Jubelin to foreground the book's

anti-heroic emphasis (see Figure 1). The image is a close-up in petit point,

or needlepoint stitch, of the face of a polar explorer that is

disintegrating. This disturbing image is placed within a bombastic gilt

frame to explicitly underline the book's overriding thesis: how the

traumatic experience of failure in both the British and American

expeditions was reworked to turn the official version of events into

something worthy of public reverence.[3]

Gender on Ice was a case study, rather than a highly

theoretical work, that at the time tried to break new ground by bringing

colonial discourses of exploration, science, and adventure not only

under the consideration of gender studies, but into conversation with

cultural studies of race and ethnicity. In this project, the parameters

of gender studies were stretched to include its historically "other"

subjects, marking a shift in then current feminist practice. Thus,

Gender on Ice was not a book about women per se—though the

history I tell does bear directly upon the condition of women and

relations of gendered power during this period—but a feminist

critique of a gendered concept of heroism associated with the new

importance given to turn of the century polar exploration as a source of

national virility and toughness. By asking, somewhat ironically, what

types of white men the Arctic and Antarctic make, the book analyzes how

reaching the North Pole and the South Pole functioned as a testing

ground of masculinity, where there was shame attached to losing, and

thus failure to demonstrate manhood.

The denial of failure at each pole by both the British and the

Americans establishes a continuity between two national events. I focus

on the tragedy of the failed British polar expeditions of Captain Robert

Falcon Scott to provide important contrasts and parallels with U.S.

polar exploration narratives. I explain how Peary's very American

scientific enterprise, which stresses tangible results, contrasts with

Scott's account, which also understood the expedition as making

contributions to science, but which followed British literary and

military traditions valorizing the inner qualities of tragic

self-sacrifice rather than performance and achievement. Drawing on the

letters and diaries of those members of Scott's expedition who were

denied power by their social position, I examine how Antarctica becomes

a discursive space. Here a nationalist myth was established in which

writing itself becomes a means to mythologize an ideology of British

white masculinity while, paradoxically, the male body is ignored. Thus,

in the Scott narrative, examples of the men sleeping in tents or on a

ship together, emphasizing the closeness of their gendered, physical

bodies, are ignored and replaced by moral character. Scott claims that

he exposed himself and his men to additional dangers and personal

sacrifices, and connects his actions to a higher national mission as

defined by the metaphor of tragic self-sacrifice, providing the

foundation on which a kind of white heteronormative masculinity becomes

heroicized.

In contrast to the British, the Americans try to produce a narrative

of masculinity that is part of a scientific tradition worked

discursively to erase the significant presence of Inuit women, men and

the participation of Matthew Henson. There is a larger emphasis on

exteriority, where successful performance and achievement matter most.

While the tragedy of Scott's failed expedition to the South Pole is

acceptable within the parameters of the literary, there is no place for

failure within the ideological narrative of scientific progress that

framed the discourses of the Peary expedition.[4] As a result, Peary's

achievement was never scientifically disputed.[5] This inability to

acknowledge outright the failure of the Peary expedition, I argue,

explains why the critique of Peary remained narrowly focused on

establishing or disputing the accuracy of Peary's claim to the North

Pole and did not resonate more widely as in the case with Scott's

expedition.[6]

These questions, in the context of my book, are meaningful in terms

of the unacknowledged failure enacted not only at the North Pole at the

early part of the 20th century, but also in the later part of the

century during the Vietnam war and at the time of the book's writing,

the first Persian Gulf War. Gender on Ice has been my attempt to

explain the interconnections between the multiple narratives of national

identity, scientific progress, modernity and masculinity across the

national cultures of the United States and the United Kingdom. In what

follows, I will return to how these discourses are invoked and

re-narrativized in the work of Isaac Julien and Connie Samaras.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

Next page

|