Author’s note 1

Giuliani Said Not To

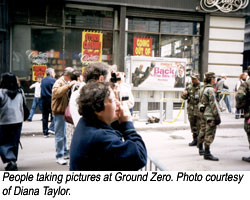

Giuliani said not to. The policeman yelled at people: “Put your cameras away, show some respect. This is a graveyard, not a place to come and gawk.” “Put your cameras away,” shouted the policewoman. “Keep the line moving.” “This is a crime scene, no pictures,” yelled a third. I did not have my camera with me on that day (September 29), but I had already taken pictures the previous week when people were first allowed to walk to the area around ground zero. On my first visit, I walked down Broadway in a crowded line of people who were tearful, stunned, angry, even defiant. But each person had a camera pointed toward what used to be the World Trade Center towers, to take pictures of distant and hard to see smoke and rubble, peeking around trucks, guardrails, and workers who were blocking the view.

The week before (on the 14th) I had gone from the Upper West Side where I have been living this year, to St Vincent’s Hospital in order to be closer to where it happened. I also went to a candle-light vigil at Union Square that had been announced informally on various flyers and Internet sites. I had not known whether it was appropriate to go to the hospital area where some of the injured had been taken and where families were still looking for the missing. Certainly I had not felt comfortable bringing a camera along. But, as soon as I got there, I bought a disposable camera and took pictures of the signs, of people holding them, of streets blocked, of the silent crowds at the vigil. I took pictures of pictures, of people looking at pictures, of people taking pictures. All the while I wondered about what I was doing – what was I after? What did this desire to snap the shutter – as uncomfortable as it was uncontrollable – mean?

Commentators have agreed that the September 11 attacks are “the most photographed disaster in history” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett). Well-known photographers and photojournalists and ordinary snapshot takers like me have all been photographing. Within the first four minutes of the first impact, the New York Times had dispatched four photographers on assignment. One hundred people eventually submitted images for the front page of September 12. The event marked us visually at the time, as people watched live, and then in unremitting replay, planes hitting towers, towers falling, people jumping, running, screaming. Even as we watched, we wanted to record everything ourselves – however grainy, small, amateurish – on home videos, digital or analog cameras. I have even gotten together with friends to compare the snapshots we each took, snapshots that require narratives and explanations because, ultimately, not much is visible on them, or, better said, what we experience as utterly extraordinary appears just too ordinary on our snapshots. Websites have been created to collect the images of amateurs and professionals, galleries have invited people to submit their images for public viewing, images are being sold for benefit purposes, exhibitions have opened around the country, magazines and newspapers continue to publish and republish professional and amateur photographs. “It’s caused a sea change,” reported the front-page photo editor of the New York Times, Philip Gefter, at a panel at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. The paper’s editors decided that people want to see as much as they want to read, and thus in the New York Times there are more photographs, they are bigger and generally in color, and they are more creatively laid out on the pages of the newspaper. In Gefter’s words “words are cerebral, but pictures are visceral.”

Certainly, still photography has emerged as the most responsive medium in our attempts to deal with aftermath of September 11. But what does it mean to take pictures at the sites of trauma? Is it disrespectful, voyeuristic, a form of gawking? Or is it our own contemporary form of witnessing, or even mourning? I started thinking about these issues specifically in response to the ban on photographs – a very short-lived ban, as it turned out, since later a viewing platform seemed actually to invite photography – but one that seemed to say something important about the relationship of photography to trauma. How, on the one hand, has photography affected the public and private process of mourning and memory and what, on the other, can the photographic acts of Fall 2001 tell us about the testimonial functions of photography? How has photography inflected the ethics and the politics of grief?

- Earlier versions of this article appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education Review, in the Brown Alumni Magazine and in Judith Greenberg, ed. Trauma at Home (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003). I would like to thank Judith Greenberg, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Temma Kaplan, Lorie Novak, Leo Spitzer, Diana Taylor and Barbie Zelizer for sharing their images and their thoughts about photography and memory with me.[↑]