“Homosexuality” or “sodomy” was prohibited in the armed forces for a very long time, although many people who were in the military identified as LGBQ and even more had non-heterosexual sex during the prohibition. Discharges for homosexuality date back to the Revolutionary War. 1 The military attitude toward LGBQ exclusion has not been a simple one. For example, studies have documented that the military has often decreased its discharges of soldiers for homosexuality during times of war. 2 “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” made it clear that no one would be discharged from the military for “telling” that they are gay if they are suspected of “telling” in order to escape required service. 3

The ban on LGBQ participation in the military was implemented through various regulations over time. For example, a regulation promulgated in 1969 listed “sexual perversion” as grounds for an undesirable discharge for unfitness. 4 Sexual perversion included “lewd and lascivious acts, homosexual acts, sodomy, indecent exposure,” and “indecent acts with or assault upon a child.” A 1981 regulation stated:

Homosexuality is incompatible with military service. The presence in the military environment of persons who engage in homosexual conduct or who, by their statements, demonstrate a propensity to engage in homosexual conduct, seriously impairs the accomplishment of the military mission. The presence of such members adversely affects the ability of the armed forces to maintain discipline, good order, and morale; to foster mutual trust and confidence among servicemembers; to ensure the integrity of the system of rank and command; to facilitate assignment and worldwide deployment of servicemembers who frequently must live and work under close conditions affording minimal privacy; to recruit and retain members of the armed forces; to maintain the public acceptability of military service; and to prevent breaches of security. 5

Trans people have been and still are excluded from military service through different policies (although exclusions on the basis of sexual orientation were also at times used against trans people). For example, courts have upheld courts-martial for cross-dressing as “conduct unbecoming.” 6 Also, transgender people are often refused or discharged from service as being psychologically and/or physically “unfit” to serve. 7 Nonetheless, trans people are far more likely than non-trans people to have a history of military service. A recent study showed that twenty percent of trans people have a history of military service, while only ten percent of the general population of the US has such a history. These numbers would be even higher if some trans people were not turned away when they tried to enlist. 8

“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was passed in 1993 during the Clinton administration, supposedly to loosen or liberalize the total ban on service by LGBQ people. While “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was promoted as a “compromise,” it expressed deep homophobia: “The prohibition against homosexual conduct is a longstanding element of military law that continues to be necessary in the unique circumstances of military service.” 9 While LGBQ people were technically permitted to serve, they could still be discharged for having gay or lesbian sex (“engaging in a homosexual act”), for marrying or attempting to marry someone of the same “biological sex,” or for stating that they were “homosexual or bisexual”—in other words, for “coming out” or “telling.” 10

The complex implementing regulations of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” set further limits, many of which were at least theoretically for the benefit of closeted LGBQ people in the military. Command officers were not supposed to ask soldiers about their sexual orientation and investigations of violations of DADT were supposed to be restricted in a number of ways. These restrictions often did not translate into reality. The military discharged many members of the armed forces under DADT, in some cases even more per year than they had before the “liberalization” of the exclusion. In 2001 alone, 1,273 people were discharged under DADT. Black women and youth in the military were disproportionately likely to be discharged under DADT. 11

It is difficult to fully map the nature and extent of the impact of DADT, as well as of previous exclusions of LGBQ people from military service. We recall one of our former clients, a homeless Black transgender woman Vietnam War veteran with disabilities. She sought access to veterans’ benefits. However, she had received a dishonorable discharge for “misrepresentations” with regard to her “history of homosexual acts.” As a result of her dishonorable discharge, she was not eligible for benefits—even medical care.

In the immediate aftermath of DADT, a rash of intense violence and harassment toward soldiers perceives as LGBTQ swept the military in an apparent backlash to what some perceived as a “pro-gay” move. 12 Some people who were severely harassed for being gay—or being perceived to be gay—were then investigated under DADT when they reported the harassment to their commanding officers. Barry Winchell, a non-trans man who was in a relationship with a transgender woman, was murdered after being turned away when he tried to report harassment. Presumably, many LGBQ people were not able to take advantage of options that were available to straight members of the armed forces with regard to their queer families. For example, Monica Hill, a captain in the air force, was asked invasive questions about her sex life after she requested a deferment of active duty to care for her terminally ill partner. She was discharged from the military shortly after her partner died. 13

Fewer people entered or continued military service than would have if LGBQ people had been allowed to serve openly, including those people who would not have been discharged, those who would have chosen to enlist, and those who would have chosen to stay in the military longer. Many agreed that this reality impaired the size and effectiveness of the military. Some were concerned about this impairment, and others were cautiously pleased. 14

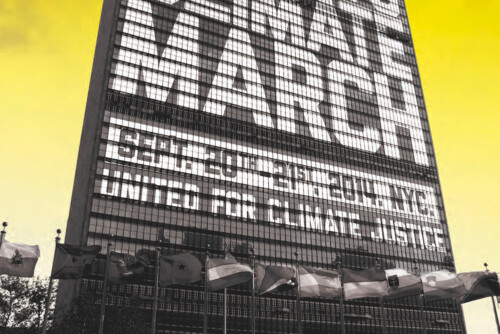

The repeal of DADT went into effect on September 20, 2011. 15

Analysis

The DREAM Act and the repeal of DADT had very different constituencies, histories, and end goals. For proponents of the original DREAM Act, the bill responded to the fact that draconian anti-immigrant laws have left very few, if any, paths for undocumented youth to access either higher education or protection from deportation. 16 The original momentum around the repeal of DADT developed as a response to homophobic military policies. 17 One became a military-related bill quietly and over time, while one was explicitly and solely about expanding participation in the military. The latter passed while the former did not. However, both bills were put forward as potential partial solutions to discrimination and marginalization, and both can help us understand the four main ways that the MIC, the NPIC, and electoral politics manipulate and undermine social-justice efforts: 1) co-opting efforts toward social change into expansions of US military capacity; 2) fueling approval for elected officials who promise a liberal agenda, but who do not change existing social hierarchies and who worsen the maldistribution of wealth and power; 3) creating division among groups that might otherwise recognize their common interests and join together against dominant power structures; and 4) incentivizing social-justice movements to focus on minor reforms rather than fundamental change.

Destruction of Lives and Communities through Military Action

The NPIC, MIC, and politicians have used the DREAM Act and the repeal of DADT to expand war-making both through funneling more bodies into the MIC and through lessening resistance to and increasing the apparent legitimacy of military projects. Because the DREAM Act did not pass, the repeal of DADT has had a greater impact on increasing military capacity, but the support for both measures has been deeply tied to military goals.

The United States continues to engage in wars and military actions against and within Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Libya, Yemen, Syria, Palestine and many other countries, benefiting the profit-making enterprises of defense contractors and corporations. In addition to our own wars, the United States also provides financial and logistical military assistance to its allied countries–such as Israel and Egypt–enabling additional destruction and financial gain to the corporate sector. 18 Rape, the killing of civilians, including children, and the devastation of infrastructure are all integral parts of these military projects. 19 These wars continue without a draft, with an “all-volunteer” military. As the government becomes more (clearly) intertwined with corporate interests, sustaining wars abroad also sustains neoliberal economic structures. 20

Since the DREAM Act did not pass, it has not funneled more immigrant youth into the military. Of course, immigrant youth and youth of color were already recruited into the military in great numbers; the defeat of the DREAM Act has also done nothing to stop the flow. The repeal of DADT, however, has probably increased the ability of the US military to continue to meet its recruitment and retention goals, as critics predicted before its repeal. “The immediate and long-term results of dismantling DADT will be the swelling of the ranks of a massive military industrial complex, making it a more effective fighting force of death and destruction. When there are those that say all this was a success for the movement, one must ask, for whom?” 21 Some LGBQ veterans who were discharged under DADT decided to reenlist. 22

Indeed, even beyond the increase in recruitment and retention of LGBQ people, the repeal of DADT has provided the military with greater access to all youth. A number of schools, such as Harvard, that used to forbid military recruitment or did not have ROTC programs on campus have now welcomed back the military and given recruiters access to their students. Ironically, in many schools military recruitment and/or ROTC programs were not originally banned because of opposition to the homophobic exclusions, but because of pressure from students opposed to the Vietnam War and US imperialism. 23 The repeal of DADT may have also created other unexpected advantages for the military. One study found that not only has permitting LGBQ people to serve openly not harmed the military’s ability to “do its job,” it has improved military capacity through “removing needless barriers to peer bonding, effective leadership and discipline.” 24

Without large numbers of voluntary recruits—and programs like stop-loss that renege on promises made to recruits—the military would need to turn to a draft to generate sufficient bodies to fill its ranks for future wars at the scale of the wars on Iraq and Afghanistan. A draft would likely dramatically increase domestic opposition to U.S. military actions as it did with the Vietnam War. Thus, in multiple ways, increasing recruitment increases the ability of the US to continue to wage war. 25

Furthermore, the rhetoric of both the fight to pass the DREAM Act and the fight to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” has, at least indirectly, defended the US military and its actions. Activists have pointed out that advocating against DADT involved at least passive acceptance of war: “Nowhere in the call to remove DADT was there a call to the end of the wars in Afghanistan or Iraq.” 26 The fact that LGBQ and immigrant movements were pushed into the role of apologists for the US military may have forestalled progress on curtailing military violence.

Some people from queer and trans communities have challenged the direct link between, in Sean Dinces’ words, the “rhetoric of the movement in favor of the repeal of DADT and the intensification of military involvement in places like Iraq and Afghanistan.” For example, Dinces critiques the rhetoric of Lt. Daniel Choi, a gay man discharged under DADT who has said that he and other LGBQ people in the military were “oppressed,” “trapped,” and metaphorically “handcuffed and fettered”: “However, what you will not hear in the statements by Choi is any reference to the oppression of foreign civilian populations at the hands of US soldiers like himself.” 27 As Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore points out, “Dan Choi talks about all of America being a victim of the policy of excluding openly gay soldiers in the military, but all of the world is a victim of the US military.” 28

The repeal of DADT also continues to fuel the justification for war against Arab and South Asian people and nations as “liberating” people from repressive, homophobic regimes. As Jasbir Puar and others have documented extensively, this deeply ironic image of a tolerant, inclusive, liberal democracy (US sexual exceptionalism) helping the poor brown women and gays of the world by dropping bombs on them has been extensively mobilized to justify war. Our newly “gay-friendly” military lends more force to these rationales for destructive violence, despite their absurdity.

In the outcry over the sexual torture of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib, some White US citizen LGBQ commentators seemed to see themselves or LGBQ members of the US military as the victims:

Patrick Moore, who … sets up the (white) gay male subject as the paradigmatic victim of the assaulting images, stated that “for closeted gay men and lesbians serving in the military, it must evoke deep shame.” … To foreground homophobia over other vectors of shame—this foregrounding functioning as a key symptom of homonormativity—is to miss that these photos are not merely representative of the homophobia of the military; they are also racist, misogynist, and imperialist. To favor the gay male spectator—here, presumably white—is to negate the multiple and intersectional viewers implicated by these images, and oddly, is also to privilege as victim the identity (as fictional progressive coherence) of white gay male sexuality in the west (and those closeted in the military) over the signification of the acts, not to mention the bodies of the tortured Iraqi prisoners themselves. 29

Now that gays may serve openly in the military, are some LGBQ people in the US less disturbed by the knowledge that Arab bodies are being killed, tortured, and raped? With their “shame” eased, will they continue to disavow responsibility?

Political Advantage without Meaningful Change

In Bell’s classic piece on interest convergence, he explains that Brown v. Board of Education was decided only because it protected and promoted white supremacy at least as much as it advanced racial justice. He argues that the decision in fact helped to sustain white power globally, by legitimating the rhetoric of past and future US military campaigns: “[T]he decision helped to provide immediate credibility to America’s struggle with Communist countries to win the hearts and minds of emerging third world peoples…. Brown offered much needed reassurance to American blacks that the precepts of equality and freedom so heralded during World War II might yet be given meaning at home.” 30 Similarly, politicians could support social-justice bills such as the DREAM Act and the repeal of DADT only because these bills also served the interests of entrenched power structures–the military industrial complex and by extension capitalism, white supremacy, and US imperialism.

When Senator Barack Obama campaigned for president in 2008, the United States was already deeply entrenched in wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Obama promised to end the Iraq War, support comprehensive immigration reform, and support the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Once inaugurated, he hesitated to deliver on his promise to end the war and increased the number of deportations. The DREAM Act and the repeal of DADT offered opportunities both for him and for the Democratic Party to deliver on at least some aspects of his campaign promises, and both bills received support from the Democratic Party and the Department of Defense.

In supporting these bills, President Obama and Congressional Democrats were able to support ongoing and additional wars abroad while at the same time presenting themselves to their base as supporters of immigrant and LGBQ rights. Politicians who supported the repeal of DADT were able to win back approval from “the gay vote” without upsetting the status quo and while building the military, without the usual negative fallout from liberal voters. As Ethan Weinstock wrote at the time:

“[President Obama]’s push to repeal DADT comes at a time when his approval ratings have been below 50 percent since November and the mainstream media have painted a picture of a politician who is increasingly unable to follow through on his campaign promises. A repeal of DADT, or at least significant progress in that direction, will prove to the liberal base that championed his campaign that he still has their interests in mind, while not rocking the boat of perceived bipartisanship as much as an endorsement of same-sex marriage or even a more vocal opposition to DOMA would. 31

The interests of the Department of Defense aligned with the repeal of DADT and partially aligned with the DREAM Act. The mere fact that both the DREAM Act and the repeal of DADT were attached to the defense bill indicates that both were of interest to the MIC. In fact, according to UC San Diego professor Jorge Mariscal, the DREAM Act was “largely developed by the Pentagon.” 32 Senator Dick Durbin’s testimony in favor of the DREAM Act was not about education, but rather about making a “pool of young, bilingual, US-educated, high-achieving students available to recruiters.” 33 As The Wall Street Journal reported, many involved in military recruitment and development completely supported the DREAM Act:

Pentagon officials support the Dream Act. In its strategic plan for fiscal years 2010–2012, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness cited the Dream Act as a “smart” way to attract quality recruits to the all-volunteer force. …

“Passage of the Dream Act would be extremely beneficial to the U.S. military and the country as a whole,” said Margaret Stock, a retired West Point professor who studies immigrants in the military. She said it made “perfect” sense to attach it to the defense-authorization bill.

Louis Caldera, secretary of the Army under President Bill Clinton, said that as they struggled to meet recruiting goals, “recruiters at stations were telling me it would be extremely valuable for these patriotic people to be allowed to serve our country.” 34

The DREAM Act was even included in the Department of Defense’s 2010–12 Strategic Plan to help the military “shape and maintain a mission-ready all volunteer force.” Strategic Goal 2 specifically mentions the DREAM Act as a means to “[achieve] quarterly recruiting quality and quantity goals,” citing military access to “once-medically restricted populations as well as the DREAM initiative.” 35 The “once-medically restricted populations” that that DoD’s strategic plan refers to could have included LGBQ and trans recruits; the DREAM “initiative” of course referred to immigrant recruits. Thus, the interests of dominant and marginalized groups seemed to converge around the repeal of DADT and the passage of a military-inclusive DREAM Act—although, in the case of the DREAM Act, that level of interest convergence was not enough. Republicans held the line against immigrants to defeat the DREAM Act. While the Republican filibuster appears counter to the interests of the MIC, it remained consistent with galvanizing and catering to xenophobic and racist sentiment. Meanwhile, the Democrats who supported the act were able to gain some popularity with “the Latino vote” without changing the status quo.

Division among Communities and Movements

The involvement of the NPIC, the MIC, and the Democratic Party in efforts on behalf of the DREAM Act and the repeal of DADT has sown divisions rather than solidarity among marginalized groups. Advocacy for both bills focused on seemingly uncomplicated discrimination against “sympathetic populations,” making them strong contenders for non-profit organizational backing, funding, and other support.

Advocacy for the DREAM Act drew upon the fact that it would affect undocumented youth who, despite working hard, staying out of “trouble,” and contributing to the economy, cannot access higher education. The National Immigration Law Center stated: “The DREAM Act gives undocumented students including high school valedictorians, varsity sports stars, and class presidents a way to obtain legal residency. … More often than not, [these students are] deeply rooted in their communities through church work, volunteering, and other extracurricular activities.” 36

This messaging created a sharp distinction between “good immigrants,” such as “faultless” undocumented children who turn out to be valedictorian church volunteers, with “bad immigrants,” like their parents or those youth who neither get great grades nor practice Christianity. Raúl Al-qaraz Ochoa, an immigrant young person who could have benefitted from the DREAM Act, pointed out some of the damage this type of framing can do: “[They] are vilifying and criminalizing our parents …[arguing that] you shouldn’t have to pay for the illegal behavior of your parents.” 37 Yasmin Nair further explained, “Over and over, these youth describe themselves as exceptional immigrants, pointing to their academic achievements and exemplary citizenship. One of the chief ironies of the DREAM Act is that it requires such students to rhetorically turn against their own parents.” 38

The repeal of DADT also drew upon the fact that it affects loyal, patriotic LGBQ people who want to openly and fully participate in the US military. 39 Like the immigrant rights movement, LGBQ messaging for DADT repeal often drew a distinction between “good” and “bad.” LGBQ people who were in the military, wanted to join the military, or were discharged from the military because of their sexual orientation were “good” and not to be confused with LGBQ people who were critical of their government, who saw themselves as choosing queerness rather than being born into it, or who were incarcerated, disabled, and/or discriminated against for multiple reasons.

Mainstream non-profit support for the passage of the DREAM Act and the repeal of DADT continued with minimal acknowledgment of grassroots critiques. Some self-identified “DREAMers” explicitly blame the NPIC for the fate of comprehensive immigration reform and the DREAM Act’s diluted nature over time. For example, one group of undocumented youth (Undocumented and Unafraid) 40 wrote:

The nonprofit organizations and politicians pushing for Comprehensive Immigration Reform continued to try to dictate what our actions should be. We felt that a barrier in achieving legalization was the Nonprofit Industrial Complex …. The Nonprofit Industrial Complex is a network of politicians, the elite, foundations and social justice organizations. This system encourages movements to model themselves after capitalist structures instead of challenging them. In this manner, foundations control social movements and dissent; philanthropy masks corporate greed and exploitation. We reject this …. 41

- Rhonda Evans, “U.S Military Policies Concerning Homosexuals Development, Implementation and Outcomes,” 37.[↑]

- Nathaniel Frank, “Research note on pentagon practice of sending known gays and lesbians to war.” (2007).[↑]

- National Defense Authorization Act for FY94, 1993 Enacted H.R. 2401, 103 Enacted H.R. 2401, 107 Stat. 1547, 103 P.L. 160 § 571(e)(1).[↑]

- Reasons and Procedures for Discharge, 34 Fed. Reg. 7909-02 (May 20, 1969)–to be codified at 32 C.F.R. pt. 41.[↑]

- Enlisted Administrative Separations, 46 Fed. Reg. 9571-01 (January 29, 1981)–to be codified at 32 C.F.R. pt. 41.[↑]

- United States v. Davis, 26 M.J. 445 (C.M.A. 1988); United States v. Guerrero, 31 M.J. 692, 694 (N-M. C.M.R. 1990) aff’d, 33 M.J. 295 (C.M.A. 1991).[↑]

- Autumn Sandeen, “Op-ed: The Policies Keeping Trans People from Military Service,” Advocate, March 17, 2014.[↑]

- Jaime M. Grant, Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jack Harrison, Jody L. Herman, and Mara Keisling, Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011), 30.[↑]

- National Defense Authorization Act for FY94, 1993 Enacted H.R. 2401, 103 Enacted H.R. 2401, 107 Stat. 1547, 103 P.L. 160 § 571.[↑]

- National Defense Authorization Act for FY94, 1993 Enacted H.R. 2401, 103 Enacted H.R. 2401, 107 Stat. 1547, 103 P.L. 160 § 571.[↑]

- Lavers, Michael, “Former Marine Evelyn Thomas on the Fight to End Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Colorlines, Sept. 27, 2011.[↑]

- Sharon E. Alexander, Debbage, Sharra E. Greer, C. Dixon Osburn, Steve E. Ralls, and Kathi S. Westcott, “Ten Years of ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’: A Disservice to the Nation,” in Conduct Unbecoming: The Tenth Annual Report on ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue, Don’t Harass’,” Servicemembers Legal Defense Network: 16 (2004).[↑]

- Ibid., 20.[↑]

- “Obama Ends ‘Don’t Ask Don’t Tell’ Policy,” The New York Times, July 22, 2011.[↑]

- Lawrence J. Korb, Sean E. Duggan, and Laura Conley, Implementing the Repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in the U.S. Armed Forces (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, 2010), 2.[↑]

- National Immigration Law Center, “Just the Facts: Five Things You Should Know about the DREAM Act,” National Immigration Law Center website, December 2010.[↑]

- Service Women’s Action Network, “LGBT Equality,” SWAN Service Women’s Action Network website; Jorge Rivas, “‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ Disproportionately Affecting Black Women,” Colorlines, February 3, 2010.[↑]

- United States Department of State, “Diplomacy in Action” Foreign Military Financing Account Summary available at http://www.state.gov/t/pm/ppa/sat/c14560.htm; see also, Nick Thompson, “Seventy-Five percent of U.S. Foreign military financing goes to two countries,” CNN, November 11, 2015.[↑]

- INCITE!, “Khaki and Blue: A Killer Combination,” Incite-national.org.[↑]

- Harry Targ, Challenging Late Capitalism, Neo-Liberal Globalization, and Militarism: Building a Progressive Majority (Chicago: ChangeMaker Publications, 2006).[↑]

- Xavier Luis Burgos, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Challenge Anything,” Jan. 23, 2011.[↑]

- James Dao, “Discharged for Being Gay, Veterans Seek to Re-enlist,” The New York Times, Sept. 4, 2011; Sean Dinces, “‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ and the Liberal Militarist Diversion,” Truthout, July 1, 2010.[↑]

- Daniel Luzer, “Harvard Eager to Rejoin Military-Industrial Complex,” College Guide (blog), Washington Monthly, Sept. 24, 2010.[↑]

- Nathaniel Frank, “The Last Word on ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,’” Slate, Sept. 20, 2012.[↑]

- Michael Foley, Confronting the War Machine: Draft Resistance during the Vietnam War (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), x.[↑]

- Xavier Luis Burgos, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Challenge Anything,” Jan. 23, 2011.[↑]

- Dinces, “‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ and the Liberal Militarist Diversion.”[↑]

- “Does Opposing ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ Bolster US Militarism? A Debate with Lt. Dan Choi and Queer Activist Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore,” Democracy Now!, Oct. 22, 2010.[↑]

- Puar, Terrorist Assemblages, 95. (Challenging) Patrick Moore, “Gay Sexuality Shouldn’t Become a Torture Device,” Newsday, May 7, 2004 available at http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/2004-05-12/news/0405120150_1_gay-sexuality-homosexuality-gay-men.[↑]

- Bell, “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma,” 524.[↑]

- Ethan Weinstock, “Activism Under Obama: Repealing ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’,” WIN 27.2, War Resisters League (Spring 2010).[↑]

- Alejandra Juarez, “Rethinking the DREAM Act,” WESPAC Foundation (blog), Sept. 21, 2010.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Miriam Jordan, “A Route to Citizenship in Defense Bill,” The Wall Street Journal, Sept. 18, 2010. For additional discussion see, Tamara K. Nopper, “Why I oppose repealing DADT and the passage of the Dream Act,” Black Agenda Report, Sept. 21, 2010.[↑]

- Ann Nill Sanchez, “What the Dream Act Has to do with National Security.” Think Progress, Sept. 9, 2010. Citing the Department of Defense 2010-2012 Strategic plan which is no longer available online (formerly available at http://prhome.defense.gov/DOCS/FY2010-12%20PR%20Strategic%20Plan%20%28Final%20Public%29%284%20January%29.pdf.[↑]

- National Immigration Law Center, “Just the Facts: Five Things You Should Know about the DREAM Act.”[↑]

- Raúl Al-qaraz Ochoa, “Lies and Betrayals: The Coming Death of a Criminal Democratic Party,” Antifronteras, Dec. 2010.[↑]

- Yasmin Nair, “How to Make Prisons Disappear: Queer Immigrants, the Shackles of Love, and the Invisibility of the Prison Industrial Complex,” in Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, ed. Eric C. Stanley and Nat Smith (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2011), 135.[↑]

- See, for example, William Shipley, “Chief Shipley Speaks Out,” Gay Military Signal website, last updated Sept. 2015.[↑]

- “Who We Are,” Immigrant Youth Justice League: Undocumented! Unafraid! Unapologetic! website (2014).[↑]

- Neidi Dominguez Zamorano, Jonathan Perez, Nancy Meza, and Jorge Guitierrez, “DREAM Activists: Rejecting the Passivity of the Nonprofit, Industrial Complex,” Truthout, Sept. 21, 2010.[↑]