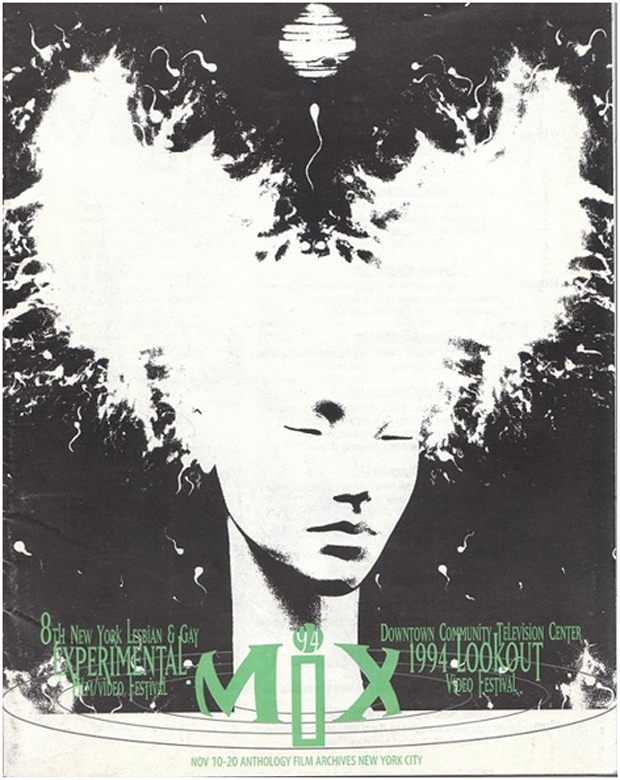

This discussion of New Frontier is important to briefly contextualize within the broader continuum of Frilot’s artistic practice. Drawing on an educational background in engineering, Frilot’s artistic practice began with two-dimensional collages, and developed using video technologies from the mid-to-late 1980s to create an expansive notion of space in her representational practice. Her twenty-minute video piece, A Cosmic Demonstration of Sexuality (1992) is one element in a larger project—a collage of the planets in our solar system, with the video itself moving through the Earth position. When she took the directorial reins of the New York Lesbian and Gay Experimental Film Festival from cofounders Sarah Schulman and Jim Hubbard in 1994, Frilot sought to “mix up” the reliance of identity-based festivals on a programming strategy that segregated films and audiences based on identity. Renaming the festival MIX, Frilot sought to unsettle the film festival paradigm and “re-mix the dialogue about programming to re-imagine a film festival on the gay circuit that engaged with race, class, and sexuality in a different way.” 1 Frilot reorganized the festival’s physical spaces to disrupt the framing of experimental, gay, lesbian, and film as stable concepts. The festival moved from its exhibition venue at the Anthology Film Archives, an East Village base for avant-garde film since the early 1970s, to The Kitchen, a Chelsea-based performance space/gallery. 2

Experimental Film/Video Festival. Designed by Reyes Meléndez in collaboration with Director of Programming Shari Frilot.

Frilot’s approach to “experimental” was not in terms of the content or form of the film/video itself, but in the approach to the work’s exhibition. Perhaps one of the most infamous programs in MIX’s 30-year history was The 1,000 Dreams of Desire, a screening of 80 films and videos guest-curated by Jim Lyons and Christine Vachon, and installed on the monitors of peep-show booths and various rooms of projection at the three-story porn palace Ann Street Bookstore, notoriously frequented by an investment banker class of white men. Frilot recalls:

I don’t think women had ever even been in that space. It was pretty gross. We went in and washed it all down, burned a lot of incense to make it smell good and then reprogrammed the entire space with gay experimental film. 3

Frilot also oversaw the development of different models for exhibiting and engaging with films throughout the festival, including the Go!Go!SPOT, a “pre/after show playground featuring [a] café, bar, music, and interactive installations in a leisure lounge setting;” 4 and the Video Gong Show, an event in which any artist could submit their films and videos to be screened in a bar with audiences cheering to indicate their likes/dislikes to a panel of “celebrity judge drag queens.” 5

Guest curators from diverse communities were invited to participate in MIX’s programming, and the festival collaborated with television centers and local event organizers connected with communities of queer artists of color. Frilot’s strategies for expanding the terms of gay and lesbian festivals, experimental film, the physical exhibition space of the festival, and the audiences interpolated into the festival culminated in the production of Victoria MIX, “the first queer film festival ever to take place in Harlem.” 6

As the director of programming at Outfest (1998-2002), which like other identity-based GLBT festivals has often taken an increasingly conservative and homogenous approach to “gay and lesbian” films and audiences, Frilot initiated Platinum Oasis, an all-night, one-time performance and installation exhibition, with performance artists Ron Athey and Ms. Vaginal Davis as the king and queen of the event. Held at the Coral Sands, a “crack-fisting motel” in Los Angeles, each of the different rooms in the motel presented some kind of performance; an artist created “set,” or an installation that would call in visitors to participate physically. Frilot describes her motivations and how they informed the curatorial philosophy:

I wanted to go back to what queer was—how fabulous and wrong and edgy and how dangerous it was … [Platinum Oasis] lasted from the afternoon, and went overnight into the next morning—setting up a landscape for devious curiosity with no bounds. We wanted to create this environment, even if it was just for a little moment, where there was … a cornucopia of exploration and adventure alongside sexuality and art. 7

These explorations in exhibition strategies to captivate audiences around art on an erotic, bodily level are central to Frilot’s approach to New Frontier and her curatorial experiment in physical cinema.

Frilot’s experimentation with exhibition and curatorial strategies to captivate audiences on an erotic, bodily level opens the possibility to refigure racial, sexual, and gendered subjectivities beyond fixed categories of identity. This work continues to inform and animate Frilot’s curatorial practice and her engagement with “physical cinema” at New Frontier. Recognizing the curator’s role as literally making a place for bodies’ engagements with the moving image, how might curatorial practice itself be taken up as an object of study by film scholars? If the objects we study shape our theories, and the theories we use frame our objects, what kinds of ways of knowing and experiencing the cinematic are produced through curatorial engagements with and interventions into the moving image? How can we think of curatorial practices as intricately tied up with formal filmmaking strategies, critical textual readings of films, and modes of spectatorship?

Conclusion: Finding the Body, An Other Kind of Love

This essay considers the way Shari Frilot’s curatorial strategies for New Frontier, during its exhibitions between 2007 and 2011, have incited embodied, participatory relationships that reframe linear relationships between the spectator and screen, and generate new dynamics that require people’s collective presence to experience cinema. Within a contemporary landscape of expanding (and collapsing) capitalist systems that employ the moving image to eat away at our bodies, feminist artistic and curatorial interventions are urgently needed to reframe the terms of our engagement with screen, new media, and digital cultures. Further, research and scholarship on the curatorial and exhibition practices around film are critical for exploring how desires are both informed by and formative of repressive cinematic apparatuses, and providing different models for mediating cinema that allow for a more capacious, and coalitional film culture. In the acts of the body finding (rather than losing) itself and making its place in the world visible, audiences, curators, filmmakers, and film lovers might mediate an other kind of love around the possibilities of the cinematic, “the poetic and mysterious and erotic and moral.” 8

- Shari M. Frilot, interview by the author, Los Angeles, CA, 12 Sept. 2008.[↑]

- Frilot 2008.[↑]

- Frilot 2008.[↑]

- 1993 MIX: New York Lesbian and Gay Experimental Film/Video Festival, 3.[↑]

- The description of the Video Gong Show reads that after “Ten years of you (the queer experimental film and video marking and viewing public) submitting to Our (the Valiant fest organizers) curatorial choices (wise as we feel they may be!) … tonight the choice is yours!”[↑]

- 1996 MIX: New York Lesbian and Gay Experimental Film/Video Festival 10th Anniversary Catalog, p. 15. Victoria MIX took place at the Victoria 5 Theatre at 235 W. 125th Street, November 14-24, 1996.[↑]

- Shari 2009.[↑]

- Sontag 1996.[↑]