New Frontier and “Physical Cinema”

Established in 2007 as an experiment in the exhibition of digital art works, media installations, and multimedia performance, New Frontier was designed within a deliberately social setting that fosters collaboration and exchange, and has been curated to bring together artists, filmmakers, and media scientists who are innovating models for cinematic storytelling. Set in the snowy, ski resort town of Park City, Utah, New Frontier is an initiative of the Sundance Film Festival, one of the most prestigious and value-producing film festivals in the United States. Unlike the situation in many countries that have national film funds or boards, the United States’ federal government’s lack of infrastructural support for independent filmmaking has positioned Sundance as a primary institution for the development, exhibition, and discovery of American independent film. During Geoffrey Gilmore’s twenty-year tenure as festival director, Sundance became a mechanism for turning independent films into profitable, commercially viable commodities.29 By 2000, the festival was inextricably implicated in the sedimentation of American independent film into what has been called “indiewood,” a simultaneously derogatory and celebratory reference to the development of the field and its replication of Hollywood’s business patterns.30 Like other influential international film festivals, Sundance has offered a platform for filmmakers not only to exhibit their films, but also to connect with industry professionals who have the necessary resources to distribute current films and finance future projects. Scholars in the emerging field of film festival studies have detailed how market pressures weigh heavily on the kinds of relationships audiences have with the films exhibited at festivals.31

In the context of Sundance and the commodification of independent film, New Frontier’s installations between 2007 and 2011 can readily be seen and experienced as wrinkles in the film festival experience. Senior programmer and curator Shari Frilot locates the motivation for founding New Frontier in a need to reappropriate screen culture, new media technologies, and cinema toward the nourishment of alternate modes of engaging cinema:

When we walk around, screens follow our bodies. Screens are in our pockets and bags. As we move through buildings and terrains, surveillance systems track us. We watch cabs drive by with TV screens. Subways are plastered with screens. You could say that we live inside of a media installation. But you can’t really call it that because it is not for art’s sake; it is mainly for commerce’s sake. I want to reclaim this environment for art.32

In the exhibition’s 2010 edition, Frilot described how the pervasiveness of moving-image technology in everyday life has created an “electroskeleton,” an electronically engineered dimension that encrusts our bodies and “structures our modern lifestyle, affecting our ethics and decision-making.”33 New Frontier seeks to resist the occupation of the cultural domain by commercial forces, transforming the conditions within which we engage the cinematic.

Actively refiguring the mode of engagement between audiences and film, Frilot describes her approach to New Frontier as an expansion of audience expectations around what Sundance has traditionally offered: American independent film. Unlike the “white cube” exhibition format traditionally found in the museum and art worlds or the “black box” exhibition format of the conventional theater, with New Frontier’s format it is deliberately not clear what, in which order, or how one is supposed to look at New Frontier. Frilot enthusiastically notes: “All those rules are gone at New Frontier. There’s no knowing anything there.”34 The location and design of the New Frontier exhibition prompts a productive disorientation that is distinct from other venues at Sundance which instead depend on film industry professionals (i.e., journalists, distributors, producers, and agents, among others) to efficiently organize themselves in order to successfully evaluate the financial and cultural worth of as many films as possible within the limited time frame of the festival.35

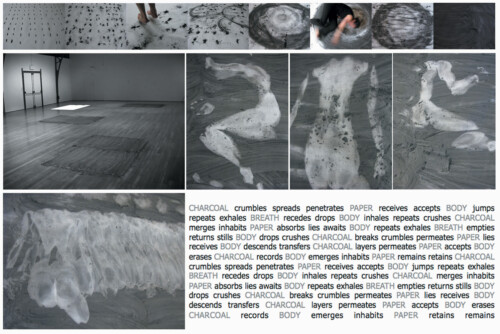

Frilot characterizes the curatorial methodology that underpins New Frontier as “physical cinema,” a framing of the cinematic that calls upon the body to dynamically participate in the process of making meaning from the work. These curatorial experiments aim to “strategically trigger sensual registers” and appeal to audiences through the body, rather than isolating the visual. The sensorial elements of the exhibition design foster a space where audiences can be vulnerable. Frilot describes how by “physically seducing [audiences] with soft couches, low lighting, and sexy music,” she hopes viewers will “not feel intimidated if they stumble around with their words.” As Frilot explains, “for example, it’s ok to stumble around with your words in a bar—in fact, it’s encouraged. People have really illuminated discussions in bars because of that.”36 The evocation of a bar’s atmosphere speaks to the attention Frilot places on how physical spaces and social contexts shape the conditions and terms in which people are able to engage with one another, and the implications for this on how audiences might relate to artistic works.

Vivian Sobchack’s work on embodiment and the sense made through our bodies—our “carnal existence”—offers further insight into Frilot’s curatorial practice. Sobchack describes our sense of self in the world as not only mediated and represented, but actually constituted through photographic, cinematic, and electronic technologies:37

As cinesthetic subjects … we possess an embodied intelligence that opens our eyes far beyond their discrete capacity for vision, opens the film far beyond it visible containment by the screen, and opens language to a reflective knowledge of its carnal origins and limits.38

Physical cinema as a curatorial methodology calls on this embodied intelligence to eclipse approaches to cinema that rely primarily on textual readings, aesthetic valuations, individual preferences, or commercial assessments. New Frontier offers a kind of cinematic intelligibility that locates the body’s position and implicates its physicality as a response to rapidly changing screen cultures and digital landscapes. This is distinct from the physicality of being moved in one’s gut while watching a powerful film. Frilot explains that with physical cinema, “your body is moving within the context of the work, completing the story with the information that the body has. The body’s movement is consummating the work, and calls the body to react in different ways.”

By calling on our bodies to be part of the cinematic experience, we actively generate meaning through our interactions with the screen. In other words, curating physical cinema requires the audience to move in order to be moved.

But move toward what? While some of the projects exhibited at New Frontier are notable for their formal technological innovations, a great number of the works curated carry provocations bent on social, environmental, and economic justice.39 As part of the legacy of black radical feminist work, Frilot’s curatorial approach to cinema locates agency and the potential to disrupt dominant narratives of temporality and spatiality within the sensual, emotive, and erotic registers of knowledge. In a talk at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for New Media, Frilot described how the development and evolution of her curatorial strategies drew on poet-warrior Audre Lorde’s theorization of the erotic.40 In her essay, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Lorde describes how the erotic is “firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed and unrecognized feeling” and must be recognized as an invaluable mode of knowing that “rises from our deepest and nonrational knowledge.”41 Lorde reclaims the erotic from its confused degeneration into “the trivial, the psychotic, the plasticized sensation,” analogous to pornography, which she asserts is, “a direct denial of the power of the erotic,” because it suppresses feeling to aggrandize sensation alone.42 Frilot takes up Lorde’s theorization of the erotic to generate critical paths for curatorial practices that navigate questions of aesthetics, difference, spectatorship, and value.

Feminist Possibilities of Physical Cinema

- For a journalistic account of Sundance’s involvement in the commercialization of American independent film, see: Peter Biskind, Down and Dirty Pictures: Miramax, Sundance, and the Rise of Independent Film (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004). [↩]

- For further reading on the development of indiewood, see: Geoff King, Indiewood, U.S.A.: Where Hollywood meets Independent Cinema (London: I.B. Tauris, 2009). [↩]

- See: Marijke de Valck, “Cannes and the ‘Alternative’ Cinema Network: Bridging the Gap between Cultural Criteria and Business Demands,” Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia (Amsterdam: Amsterdam UP, 2007), 85-122; Janet Harbord, “Film Festivals: Media Events and Spaces of Flow,” Film Cultures (London: Sage, 2002), 59-75. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- “New Frontier Sneak Peek: The Liberated Pixel,” (PDF) Sundance Film Festival press release, 16 Oct. 2010, accessed 27 Oct 2011. [↩]

- Shari M. Frilot. Interview by the author. New York, NY, June 16, 2009. [↩]

- For the first three years, New Frontier took place in the basement level of the Main Street shopping mall, located across from the historic Egyptian Theatre. The fourth year took place in three adjacent buildings of the nonoperational Miner’s Hospital, and in 2012, New Frontier will take place in a former lumber-yard building renovated into an event space and restaurant. [↩]

- Frilot 2009. [↩]

- Vivian Sobchack, “The Scene of the Screen: Envisioning Photographic, Cinematic, and Electronic ‘Presence,’” Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley: U of California P, 2004) 135-162. [↩]

- Sobchack 2004: 84. [↩]

- Including work by Paul Chan, Matthew Moore, Shirin Neshat, Sam Green, Omar Fast, Martha Colburn, Hassan Elahi, Petko Dourmana, The Bruce High Quality Foundation, Nao Bustamante, and Travis Wilkerson, to name a few. [↩]

- Shari Frilot, “The Power of the Erotic: Curatorial Strategies at Sundance’s New Frontier,” Presentation at the Art, Technology, and Culture Colloquium, UC Berkeley, 18 Feb. 2010. [↩]

- Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Trumansburg: Crossing Press, 1984) 53. [↩]

- Lorde 1984: 54. [↩]