The sense of a generally shared repertoire of images, and the dissolution of individuality in family photography, led Novak to begin collecting family photographs among friends and family, students and colleagues. ” I wanted to see if other women’s images were like mine,” she says of the first “Collected Visions,” a slide installation of snapshots examining the representation of girls and women’s development from childhood through adolescence (Hirsch 1998, 20). Some of the images are overlaid with pages from classic feminist

texts (A Room of One’s Own, Writing a Woman’s Life) held by Novak’s hand, texts that signal the alternate plots that Novak envisions for her traditionally represented female subjects.

“Collected Visions” began as a bold extension of Novak’s autobiographical project: “I wanted to see if other women’s images were like mine.” It grew into an elaborate World Wide Web project created in collaboration with Clilly Castiglia, Betsey Kersaw, and Kerry O’Neill (http://collectedvisions.net) that radically transcends the personal in favor the collective. “Collected Visions” consists of an extensive display and examination of informal camera images collected from hundreds of subjects. The website allows for a number of different forms of participation by its visitors: we can search the ever-expanding archive of images, we can use individual images as the base for writing photoessays to submit to the “Collected Visions” gallery, we can view past essays in the “Collected Visions” museum, and we can consult a growing interdisciplinary bibliography of works on family photography and memory. We can also submit our own snapshots to the site via the web or by mail, and we can submit stories that accompany the pictures. Those pictures are then catalogued according to a number of categories that in themselves constitute a rich analysis of the conventions of family photography and its role as a vehicle of family memory: who is in the photograph (e.g. “girl or woman alone,” mother and children”,” brothers,” “pets,” “friends”), the genre of the photograph (e.g. “graduation,” “on vacation,” school picture,” birthday party,” “family reunion,” “crying or pouting”) and the time period of the image. One can also search the archive by the name of the donor. The site is visited often and after being up since 1996, it now contains over 2,500 images. It is accessible worldwide and Novak hopes for ever-broader participation in the form of new images and essays: “It is essential that the gallery contain multiple voices and points of view. I check for submissions daily, looking forward to the influx of new and diverse stories with great anticipation” (Hirsch 1998, 26).

The ability to submit photographs and become part of the work, and the invitation to write essays about the photographs, are the most innovative aspects of the site, which thus becomes a collective autobiographical project. While some people write photoessays about their own images, it turns out that a majority of the essays submitted are about the photographs of others that most people actually write about as though they were of themselves. As Novak writes on the site itself, “maybe writing about the resonant images of others frees authors from the personal baggage surrounding their own photographs and allows them to be more revealing.” But are photographs really as anonymous and interchangeable as all that? What happens to the familial look when one’s own photos are surrounded by 2,500 others? How does this new context affect our relationship to our own images? There is a risk that, unmoored from their specific familial context, family pictures become too generic and thus devoid of the aura that lends them meaning. At the same time, affirming the power of the familial look comes dangerously close to affirming too uncritically and unselfconsciously the value of family itself, and most specifically of biological family. Novak’s site strikes a successful if ever unstable balance between these extremes: it both affirms and subverts the aura of the individual family and the snapshot as its technology of representation.

For me as a visitor, Novak’s site always introduces a tension between an autobiographical impulse and a more general interest in photographic representation. I must confess that searching though the archive by general categories to see multiple representations of birthday parties, superhero outfits, or girls cooking is ultimately boring. I am always much more interested in looking at images that are accompanied by essays which offer a verbal narrative to contextualize and situate them. And I am most fascinated by looking at pictures of people I know, especially at the pictures I myself or other members of my family submitted to the archive and that thus engage me in a familial look. There are 28 of them and I could look at them endlessly: I find new things each time I click to enlarge them, or place two or three on the screen together. When I see my pictures in the midst of others, they jump out and grab my attention completely. Although I like the idea of their placement next to so many others like them, this does significantly diminish the aura they have held for me. I have to work hard to separate them from the others. And still their power is always there, especially as they first come on the screen. In this new context, I see them as though for the first time. Each picture evokes layers of memory from when it was first taken, to when I first looked at it carefully, to the time I began writing about it in relation to other images of me or my family. I wonder why I chose to submit it and how, through these 28 images, my life story could be told. In these reactions I delimit personal from collective autobiography.

I was thus quite startled to find a photoessay in the CV Museum based on one of my own family photos.

Disturbingly, it is filed under the general rubric “Family Secrets;” but I myself did not intend to reveal any secrets when I submitted the picture. In the picture my parents and I are on a hike in the Carpathian Mountains shortly before emigrating to the United States in one of a few waves of Jewish emigration from Rumania in the early 1960s. These mountain vacations were a familiar feature of our life in Rumania, so much so that when we came to the United States we tried to relive the experience in our hikes in the White Mountains. There is a similar picture taken in New Hampshire and nothing, neither our expressions, nor the landscape itself, testifies to the monumental change our lives had recently undergone. There is much I could write about the Carpathian photo’s composition or about the expressions on our faces. Who took the picture, I wonder? Was it someone we met on the trail, or were we hiking with family friends as we sometimes did? For me, this picture is a space of reflection and recognition that motivated me to submit it to the “Collected Visions” site. It marks the moment before our emigration, the quality of a secular Jewish life in Rumania of which these mountain hikes were an important part. I am sutured into the photograph by the familial look that defines a boundary between inside and outside, claiming this family group as a part of the story through which I construct myself, even though I feel quite distant from the preadolescent child in the picture. This inclusion is an act of adoption and an act of faith determined by an idea, an image of family and of self-within-family. It is fundamentally an interpretive and a narrative gesture, a fabrication out of available pieces that acknowledges the fragmentary nature of the autobiographical act and its relation to reference. To me, then, this picture is the product of a process of familiality that it illustrates – the exchange of looks, both within the picture and my look of (mis)recognition now, that structures a complicated form of self-portraiture that reveals the self as necessarily relational and familial, as well as fragmented and dispersed over space and time. In this narrative, I tell myself, the family picture is a self-portrait, for the self-portrait always includes the other, not only because the self, never coincident, is necessarily other to itself, but also because it is constituted by multiple and heteronomous relations.

But there is little in my experience of this picture that I recognize in the photoessay by Adam Faja from Ann Arbor, Michigan, in February 1997. Writing in the first person, he projects himself into my own place in this familial unit. His appropriation feels invasive, especially since the feelings and reactions he attributes to the parents and the child in the picture seem to me, at least on the surface, quite distant from the ones I associate with it: “Since we’ve lived in the suburbs, mom and dad have been so closed and quiet. They only seem really happy on our summer trips back to the mountains. They take turns heading the trails but it’s hard to keep up with them. They’re so comfortable here, and I am so out of place. I wish I could like it here like they do. I’m so cold and tired and dirty, though, that all I can think about is how much longer it will be to the top. How long until we can go home.” To me my parents look rather serious, if not grim, There is no hint of a smile on any of our faces. Although the terrain was no doubt familiar to them, watching them was not like “watching a squirrel bounding from branch to branch.” This form of projection feels alienating, and I find myself wanting to protect my picture as mine, to protect the earnestness that characterizes all of our familial activities, even hiking. The familial look does allow one to say about the pictures of others, “this could have been me,” or “this picture is like my pictures;” but when it says, “this is my picture” then it feels as though some boundary has been violated. Although I am professionally interested in the conventionality and thus the interchangeability of snapshots, that interest seems to stop when I get to my own pictures. And yet I wonder if perhaps Adam perceived something of my own discomfort, of my sense of impending adolescent and cultural separation from my childhood and my European home. His identification with me, his projection of his own story or of the story he imagines does reveal something to me about myself. At the very least he shows me that the personal autobiographical narrative is still the most powerful, and thus also the most vulnerable, impulse in my experience of “Collected Visions.” But it is also alienating, perhaps mostly because his story of American suburban life feels so different from the secular European Jewish life of my childhood.

It may thus be no accident that the initials of the “Collected Visions” web site is CV: it is Lorie Novak’s own curriculum vitae. There are 128 pictures under “Novak” in the archive, including most of the pictures we already know from Novak’s projections and installations. But here they are arranged sequentially as in a photo album, juxtaposed with one another only as they would be in a photo album. Although the site contains pictures of the Novak family that were not previously used in projections or installations, I find myself drawn to the images that are already familiar to me. And these send me back to the still projections, elucidating some of the compositions, making visible some elements that were not previously transparent. Thus we can discover that the picture of the sad two-year old Lorie clutching her smiling mother’s shirt is one of a sequence of three images: in the first, both the little girl and the mother are smiling; in the second, the mother smiles and the little girl looks like she is about to burst into tears; and in the third, the mother looks serious, pained, concerned, as the now visibly crying girl hides her face in her mother’s lap. That worried maternal face is in a number of Novak’s projections, notably in “Night Sky” (1990) and more recently in “Identities (school pictures)” (1999) .

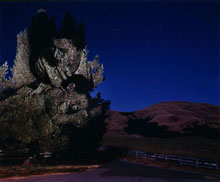

“Night Sky” is a projection of the mother and crying child unto trees in a stark southwestern landscape – only the mother’s face is clearly visible in the tree surrounded by a translucent pre-dawn sky. The child is partially hidden in the tree branches and leaves, while the tree branches on which it is projected underscore the worried look on the mother’s face. It is as though the entire landscape was haunted by this concerned maternal face, protecting the hidden child from the demons that haunt her. Or is it that the mother herself cannot protect, that the child has to cry in spite of, or because of, the mother’s presence?

The same concerned maternal face appears in the recent “Identities” hovering over a series of Lorie’s school pictures that have been projected overlapping unto crumpled paper. Here again identity is constructed through its representations over time, and it is presented as institutional rather than merely personal or familial. But the projection of the beautiful, large, hovering maternal face and the multiplication of school portraits introduces a level of anxiety and discomfort, of personal obsession into the image. The black background makes the images float in a dreamlike space. Even though the black and white maternal portrait is on a different plane from the school pictures, there is something quite hermetic and self-involved about the entire image. Here Novak has projected her mother’s face looking over images of her: mother and daughter mirror each other within the enclosures of the artist’s imagination.

Reading “Collected Visions” in relation to Novak’s larger autobiographical and familial project as it is represented in her projections and her earlier installations is not an argument for a strictly personal interpretation of “CV.” The power of this work is precisely in the tension it evokes between the personal and the collective archive. And it is here, at this juncture, that CV announces itself specifically as a feminist project, even though the images are not restricted to women. Creating this sort of archive of the representational practices of everyday life is in itself a feminist project as is the interrogation of the ideology of the family. And so is, I would argue, the structure of the artistic space, a “neutral space designed for many voices and viewpoints” (personal communication). In opening her artwork so totally to others, Novak relinquishes artistic control and enables the participation of multiplicity of voices. Her most recent iteration of Collected Visions, a computer-based projected installation with music by composer Elizabeth Brown, debuted at the International Center of Photography in fall 2000. It reclaims a bit of that control in its composition and sequencing. Still, this new installation contains images of others, as well as her own. Novak’s personal interpretation of the meaning of photography and memory continues to be based on a collected archive of memories.

For Novak, the autobiographical – both personal and collective – is the political. CV shows us something about the sometimes discomforting power of personal images, and, also, about the conventions that disguise and overshadow that power. As a feminist artist and cultural critic, as a Jewish artist, she makes us think about the representations of women and families, of the intersectionalities inflecting those terms, and the ideologies that shape those representations. By remaking personal images, she manages both to affirm and to subvert the spell they have on her – and on the rest of us. And by engaging in autobiography through the conventions of representation, she both constructs and deconstructs a personal and professional narrative through which other women can begin to perceive the forces that constrain their own self-definitions as well as the vehicles through which they can begin at least to envision some ways out of these constraints.

To view Lorie Novak’s Website about her own work, click here.

Works Cited

Adams, Timothy Dow, ed. Autobiography, Photography, Narrative, Special Issue of Modern Fiction Studies 40, 3 (Fall, 1994).

— Life Writing and Light Writing (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981).

Eakin, Paul John, Touching the World: Reference in Autobiography (Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1992).

George, Alice Rose, Abigail Heyman, and Ethan Hoffman, eds., Flesh and Blood (New York: Picture Project,1992).

Galassi, Peter. “The Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort” (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1991).

Handy, Ellen.”Fixing the Art of Digital Photography: Electronic Shadows,” History of Photography (Spring 1998).

— “Genius loci, Ingenious Locations, and Landscape Photography Today: Nostalgia, Femininity, and Looking Toward the Millennium,” Camerawork, A Journal of Photographic Arts, vol. 23 no. (Fall/Winter 1996).

Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997).

Hirsch, Marianne , ed. The Familial Gaze (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1998).

— “Projected Memory: Holocaust Photographs in Personal and Public Fantasy,” in Acts of Memory: Cultural Recall in the Present, ed. Mieke Bal, Jonathan Crewe, Leo Spitzer (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1999).

Kuhn, Annette. Family Secrets: Acts of Memory and Imagination (London: Verso, 1995).

Lahs-Gonzales, Olivia and Lucy Lippard. Defining Eye: Women Photographers of the 20th Century, (St. Louis: St. Louis Art Museum, 1997).

Noval, Trena. “In Other Worlds: the persistence of memory, life, and art: The work of AnaMendieta and Lorie Novak,” Camerawork, San Francisco, (Vol. 23 No.2, Fall/Winter 1996)

Rosenblum, Naomi. A History of Women Photographers, (New York: Abbeville Publishing Group, 1994).

Rugg, Linda Haverty. Picturing Ourselves: Photography and Autobiography (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

Spence, Jo and Patricia Holland, eds. Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography (London: Virago, 1991).

Spence, Jo. Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political Personal and Photographic Autobiography (Seattle: The Real Comet Press, 1988).D.C.

Willis, Deborah. Imagining Families: Images and Voices, (Washington : The Smithsonian Institution, 1994).