Together, Lorie Novak’s images and installations, consisting of thousands of intercalated photographs of her own family and hundreds of other people, constitute a fascinating, if unorthodox, autobiographical project. Novak portrays herself as embedded in numerous relationships – familial, generational, cultural. She interconnects her own memories with public memories of the period in which she grew up and the media images that gave her access to them – the memory of World War Two and the Holocaust, the Cold War, the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War. She examines stereotyped images of femininity and masculinity, and of other social institutions. She thus situates subjectivity at the juncture between the self-portrait and the family picture, and its representation at the juncture between personal and public camera images. Autobiography is as much collective as it is personal. But most of all, she examines the technologies of representation and communication – the camera, the museum, newspapers and television, the World Wide Web. She interrogates their hegemonic dominance, and she uses them oppositionally, as instruments of contestation.

One might think, from this brief description, that her project quickly transcends the personal and autobiographical in favor of a more public exploration. But Novak herself uses the term “obsession” when describing her relationship to camera images, and a viewer of her work cannot help but notice the obsessive repetition of a few childhood photographs and the repeated preoccupations with certain historical scenes that mark this work as deeply personal. And yet her interest in including a multiplicity of media images in her own “family album” and opening her own art work to global participation by anyone who has access to the web indicate a profound rethinking of the autobiographical project. We can turn to Novak’s work to think about the relational self-representation of contemporary women artists and about the quite permeable juncture between self-portraiture and family photography, between individual and cultural memory. It enables us to think about what this juncture means for a Jewish woman artist in particular.

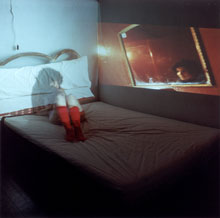

“Mirror Image” (1983), one of Novak’s earliest projections, is a photograph of a carefully staged performance composed of slides and a live appearance by the artist. The most private of domestic spaces, the bed, becomes the space of dreams and projections in which the female subject is split into two different images that stare at each other from the two sides of a mirror. As Novak describes it:

The projected slides include a bed frame and pillow from

some trip I took that is projected to scale on the edge of the

mattress so the illusion is almost perfect. The mirror on the

right is a self-portrait I took of myself in a bathroom mirror

somewhere in San Francisco. At the time, I carried a small

camera with me at all times taking slides that could later be

used as projections. I entered the installation for half the

exposure so I would appear transparent and float and

function like one of the slides. I chose to be partially

undressed with socks so as to make a reference to being a

young girl. At the time I made this, I was often using empty

beds as my stage, a site of dreams, nightmares, and

memories.

Novak has managed to create a self-portrait that contests the referentiality and plenitude of the photographic image, visually showing the subject to be composed of multiple images over time, of dreams as well as waking moments, of reflections and projections, of absence as well as presence. As the image of the photographer floats on top of her bed and the self-portrait becomes a “mirror image,” the “having-been-there” of the photograph and the singularity of the subject both dissolve. Novak has opened the privacy of her own bedroom to a multiplicity of camera gazes superimposed on one another in a space of multiple reflection.

Most of Novak’s domestic spaces are populated not just by images of the artist herself, however, but by additional familial and public subjects in relation to whom she is able, visually, to tell her own story. Several iconic images – pictures of Novak’s mother holding her, pictures of her with her mother and father, some images of her mother’s face, a few childhood pictures of her cooking or being inducted into the Girl Scouts – recur and their repetition and recontextualization punctuate her autobiographical narrative with moments of obsessive resistance. Certain spaces also serve as repeated backdrops of the projected images, and, as the same pictures reappear in new domestic settings, outdoor projections onto trees, or public sites such as Ellis Island, they are significantly reconfigured in meaning and effect. Novak’s projections are just that, projections, which present different trajectories and different interpretations of a few determinative personal narratives.

Thus in Novak’s “Fragments” (1987) we find a large black and white family picture from the 1950’s in which the artist and her parents stand below a painted portrait of the young Lorie. This image of the nuclear family reappears in a number of projections that enable her to interrogate the ways that these two genres of familial representation have positioned her as a female subject: first as the little girl in the painting commissioned by her great uncle, then as the little girl sitting on the mantle reincarnating her portrait, this time held up by her father and her smiling pregnant mother. “Fragments” is a collection of embedded images, the record of a series of superimposed projections: the fifties image is projected onto a corner wall where it fits uneasily into the space, and it is broken apart by a color photograph projected over white pieces of board onto the floor which occupies the bottom half of the work.

In her construction of “Fragments,” Novak highlights the incongruities constructing a life story. She has broken through generational continuities, signaled in the resemblance between the daughter and the pregnant mother in the fifties photograph. She has cut up the image and the frame, in order to shed its constraints. She has proposed an alternative trajectory for herself. At the bottom, upside down, in a bathing suit, lies the woman of a new generation, refusing continuity and reflection, finding herself in fragments. Next to her lie cut-up pieces of an image of a man also wearing a bathing suit. As our eyes try to reassemble the fragments, we notice hints of irreverence: her closed eyes which refuse to gaze back at the viewer or to smile like the compliant women in the black and white photos, her hand reaching into her male companion’s crotch. Conventional family pictures provide Novak with the space of disidentification. But as she so deliberately attempts to reach beyond the constraining frame of the family snapshot, Novak also affirms its power in determining her personal identity and life story.

The same black and white family photo reappears again in “In Flames” (1991) projected outdoors onto a nighttime scene of trees which appear to be on fire. At the left corner, the image is held by a hand. On the right, the red flame colors break through the white jagged frame of the photograph and wash out half of it. As the oil portrait and the figure of the pregnant mother go up “in flames,” and as the domestic space is replaced by the outdoor woods, the little Lorie in the image can perhaps find her way out of the expected trajectory of a fifties’ girlhood that has become the object of such explicitly violent and destructive impulses. Novak’s outdoor projections play with the reversibility of nature and culture (the title of one image is “Natural History”) and thus attempt to liberate the women in her photographs from anything that might be construed as a “natural” domesticity.

The most frequently re-used photograph in Novak’s work is an image of her smiling mother holding the sad or frightened two-year old Lorie as the little girl anxiously grabs her blouse. This image appears most powerfully in “Past Lives” (1987) where it shares the space with some media images that also recur in Novak’s work, visually marking her as a generational subject shaped both by the public events she shares with her contemporaries, and by her own familial narrative. “Past Lives” is a photograph of a composite projection onto an interior wall: in the foreground is a picture of the children of Izieu – those Jewish children hidden in a French orphanage in Izieu who were eventually found and deported to a death camp by Klaus Barbie. Nineteen eighty-seven was the year of the Barbie trial. This photograph of these children appeared in a New York Times Magazine article on the Barbie affair. In the middle ground of “Past Lives” is a picture of Ethel Rosenberg’s face. She, a Jewish mother of two young sons, was convicted of atomic espionage and executed by electrocution together with her husband Julius Rosenberg. In the background of Novak’s composite image, is the photograph the little Lorie who clutches her mother’s dress and looks like she is about to burst into tears.

By allowing her own childhood picture literally to be overshadowed by two public images, Novak stages an uneasy confrontation of personal memory with public history, of a familial psychodrama with the collective story of her and her parents’ generation. What drama is being enacted in Novak’s “Past Lives?” If it is a drama of childhood fear and the inability to trust, about the desires and disappointments of mother/child relationships, then it is also, clearly, a drama about the power of public history to crowd out personal story, about the shock of the knowledge of this history – the Holocaust and the Cold War, state power and individual powerlessness. Lorie, the little girl in the picture, is, after all, the only child who looks sad or unhappy: the other children are smiling, confidently looking toward a future they were never to have. Visually representing, in the 1980s, the memory of growing up in the United States in the 1950s, Novak includes not only family images but also those figures that might have populated her own or her mother’s daydreams and nightmares: Ethel Rosenberg, the Jewish mother executed by the state, and the children of Izieu, unprotected Jewish child victims of Nazi genocide. The child who lives is crowded out by the children who were killed; the mother who lives, by the mother who was executed; their lives must take their shape in relation to the murderous breaks in these other, past, lives. The representation of one girl’s childhood includes, as a part of her own experience, the history into which she was born, the figures that inhabited her public life and perhaps also the life of her imagination. Personal stories and family stories are embedded in generational stories, public histories. Novak has found a photographic mode through which to express this expanded autobiographical narrative by concentrating on the images that dominate cultural and thus also personal memory. In addition, she has found a mode of presenting the picture of herself and her mother that has such powerful resonance for her that it appears in the same frame with Jewish victims of state execution.

Novak’s images taken in Ellis Island, for example, “Altar” and “Self Portrait (Ellis Island)”(1988), similarly inscribe her own personal and family history in a larger story of Jewish group identity. Here Novak projects her own self-portrait, and a series of family pictures unto the space where her European Jewish ancestors first became U.S. subjects. Floating like ghosts over the wall and door of the room in Ellis Island, these descendants haunt a space through which their ancestors passed on their way to a new home in America. Novak allows her personal history to reach back generations, making herself the threshold for the recollection of personal, familial and social memory.

Soon Novak’s own photos, supplemented by media images and even by found snapshots, found their way into multi-media slide and sound installations still dedicated to disrupting the myth of a conflict-free family supported by the genre of the family snapshot. Works like her “Traces” (1991) and “Playback” (1992) are feminist projects that attempt to weaken the solidity and reality of traditional gender roles. These projects relativize traditionally feminine roles by placing different photographic representations of them into dialogue with one another. Photography’s way of naturalizing cultural practices makes it a particularly powerful and thus insidious instrument of social conformity that Novak contests through the multiplication of images, their juxtaposition and rapid succession, as well as their supplementation by voices and music. These installations create a very different experience for viewers than the still projections do: here we can walk through the work, becoming physically and materially implicated in a series of personal photographs which in their conventionality necessarily resemble our own, and in the media images that are part of a shared cultural memory.

“Traces” and “Playback,” however, also remain intensely personal for Novak. “Playback” begins and ends with the picture of the smiling mother holding the sad little girl. In the beginning it appears as a picture the artist is holding in her hand. In the end it is sandwiched with an unsmiling adult image of the artist, one in which she herself might well be the same age as the smiling mother was at the time of the older photo; it is then projected as the final image which dissolves to black very slowly. The little Lorie clutches at her mother’s blouse, but in the projection it looks as though she is clutching at her own adult face. As time is collapsed in the projection, Novak’s adult self is taken over by a childhood image that continues to haunt her, literally playing back her child fear and unhappiness.

The singular aura of “Clutching” is qualified and relativized and Novak’s confessed obsession with this image is weakened as the image takes its place inside the larger installation “Playback.” The installation contains numerous pictures of an ever-expanding familial group in which Novak appears not only as daughter but also as sister, aunt, cousin, and as an adult professional. These images, moreover, are further juxtaposed with media images of World War II and the Holocaust, of Vietnam, the sixties, up to the Gulf War. The dark space of the installation in which these images encounter each other is further opened up by the child’s wading pool in the center of the room, into which images of children jump at regular intervals, and by the live radio scan. These multiple sites of engagement further remove the aura of the one determinative childhood photo and open up routes of escape. Yet the sound scan that cannot be stopped and the restricted space of the wading pool certainly delimit the chances for evasion.