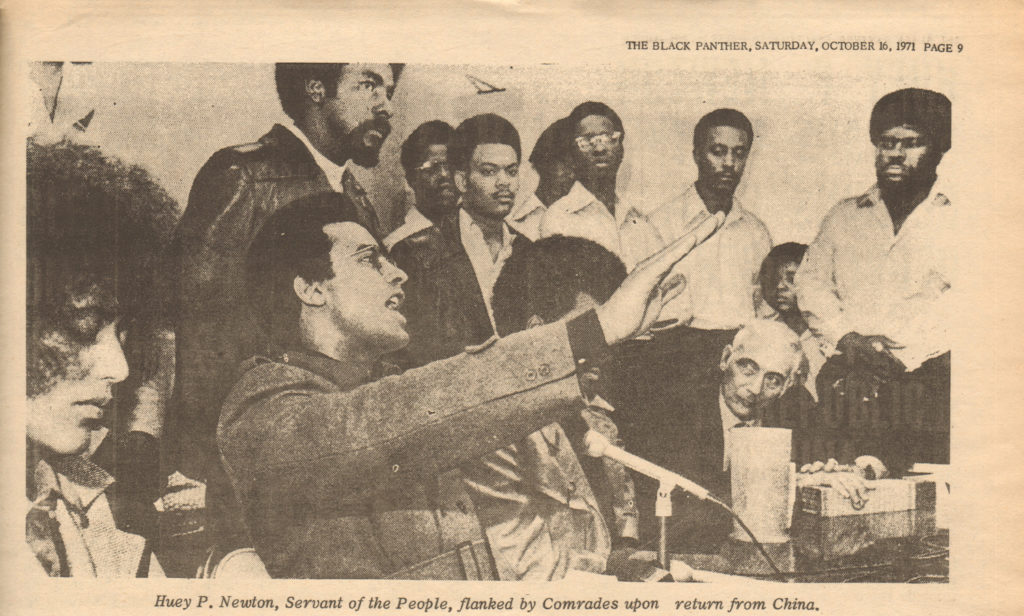

Upon his return from the People’s Republic of China in 1971, the Black Panther featured an image of Black Panther Party co-founder and Minister of Defense Huey Newton shaking hands with Vice Premier Zhou Enlai on its cover. Inside was a half-page photograph captioned “Huey P. Newton, Servant of the People, flanked by Comrades upon return from China.” Newton sits before the press, raising his arm and projecting so forcefully that the sole microphone at the table placed in front of him seems superfluous. He sits between his two fellow travelers, newly elected Minister of Information Elaine Brown and bodyguard Robert Bay. Brown, her eyes turned down, is partially cropped out of the left edge of the photograph. Newton’s hand entirely eclipses Bay’s face. At the table, a white male reporter gazes at Newton. In the background, Panther men clad in militaristic attire stand in support. The photograph is triumphant and Newton is its star. Of the many images taken of this press conference, this one was printed in the Black Panther, the official party record. Newton recognized what was at stake in a photograph, telling the press that day that “a picture is worth a thousand words.” 1 Iconic images that center men and depictions of male solidarity form the cornerstone of Afro-Asian studies, which has been overly male and heterocentric. Taking this event and image as paradigmatic of Afro-Asian studies, I explore how an image placing Newton at the optical and symbolic center while quite literally obfuscating Brown and Bay becomes archival artifact. Not taking a photograph at face value, I speculate about how images were staged, what remains occluded, and what other images exist but are buried in the archive of Afro-Asian solidarity. As the staged images from this trip to China become part of the archive of Afro-Asian studies, I argue that they in turn undergird often romanticized, masculinist narratives about Afro-Asian solidarity as political encounters between men.

This photograph marks an extraordinary turning point of Afro-Asian history in the early 1970s when China decisively shifted allegiances from the anti-imperialist third-world movement to U.S. hegemony, signaling the end of China’s revolutionary internationalism. 2 In the escalating geopolitics of the Cold War, Mao Zedong chose survival over “friendship diplomacy” with radicals around the world. Eldridge Cleaver, who led the Panther International and traveled with Brown to China in 1970 as part of the U.S. People’s Anti-Imperialist Delegation, describes the blow to left social movements: “When you see Nixon shaking hands with Mao and you know what Nixon is about, then the whole system just disintegrates.” 3 While much has been written about China’s engagements with black radicals and diplomatic normalization as separate events, I bring them into the same historical narrative. This watershed moment is not only a story of Afro-Asian encounters, but also one of U.S. empire; Nixon’s trip is more than merely context for the Black Panther Party trip, but crucial to it. Only by examining these trips together can we expose the contingencies underlying and unevenness of these Afro-Asian encounters, thus arriving at a more nuanced understanding of solidarity at this moment.

In a feminist queer reading of these archival materials, I bring normative masculinity front and center, and argue that Newton, Nixon, and Mao each played politics through staging photographs and bodily performances that reasserted their masculine subjectivity in the realm of international politics. In what follows, I situate my approach in working with this archive within feminist queer interventions in Afro-Asian studies, construct a narrative around masculine anxieties that produced these encounters, and examine the gendered dimensions and power dynamics of the Black Panther Party and Nixon trips to China in relation to bodily performance and homoerotic desire.

Charisma, Desire, and the Afro-Asian Archive

Extending feminist critiques of the centering of men and erasure of women within black radicalism, Afro-Asian studies has relied on the historical encounters of “Great Men” – the exceptional male actors of history – and so reproduced heteropatriarchy. 4 Part of the feminist queer project, then, is to decenter these historical actors and question their claims, in effect provincializing them. These world-shaping events were not merely the product of rational calculation in the interest of movement building and state making; they were also shaped by subjectivities, desires, anxieties, and failures related to masculinity. Even as I use sources such as the Black Panther, news media, and personal memoirs that center these historical actors, I attempt to decenter them by bringing different questions to the archive, and reading memoirs and images for signs of interior life, affect, and masculine subjectivity.

Another part of the feminist queer intervention is interrogating how Afro-Asian solidarity is naturalized as brotherhood that diminishes female agency in the archive and historiography. Although there are many actors to consider in this narrative, I focus on the respective prominence and erasure of Newton and Brown’s leadership in the trip to China. I turn to Erica Edward’s critique of charismatic leadership and the legibility of Afro-Asian solidarity through male homoeroticism.

Charisma connects black political subjectivity with normative masculinity, and reproduces it at the heart of Afro-Asian solidarity. As Edwards defines in the context of twentieth-century black political culture, the charismatic leader, or the “Great Man,” is “given divine authority and power, given to the people, and given for the sake of historical change.” 5 A “structure of political affect,” “charisma participates in a gendered economy of political authority in which the attributes of the ideal leader are the traits American society usually conceives as rightly belonging to men and normative masculinity: ambition, courage, and above all, divine calling.” 6 Significantly, charisma constitutes an epistemological violence that “grants uninterrogated power to normative masculinity.” 7

Afro-Asian solidarities are also in part figured as brotherhood because of the long-standing role homoerotic desire has played in mediating political encounters between male leaders. Michelle Stephens asserts that, throughout the twentieth century, the “black transnational community” was comprised of “black men traveling … in a common state of desiring freedom, language, community – and each other.” Transnational and international realms were thus “primarily a space of men desiring. 8 W.E.B. Du Bois’s Dark Princess envisions Afro-Asian unity through heterosexual romance. 9 In the Afro-Asian cultural nationalist context, Daryl Maeda observes, “Asian American men regain their masculinity by taking hold of their phalluses alongside black men doing similarly.” 10 As the Panther trip to China also shows, Robeson Frazier remarks that black travelers to China and the Chinese government constructed these realms through desire. 11

In “Between Men,” Eve Sedgwick examines a range of male homosocial bonds such as friendship, mentorship, rivalry, and homosexuality on a continuum in relation to patriarchy, and writes, “In any male-dominated society, there is a special relationship between male homosocial (including homosexual) desire and the structures for maintaining and transmitting patriarchal power: a relationship founded on an inherent and potentially active structural congruence.” 12 Extending this insight to Afro-Asian studies, the valorization of male homosocial bonds is related to the marginalization of female leadership. While I do not theorize how male homosocial desire is constituted in Afro-Asian encounters, teasing out desire between men is nevertheless productive in complicating accounts of solidarity. Reading for the intimate shows how gender and sexuality shape the political by making explicit the implicit framing of Afro-Asian solidarity through romance and brotherhood.

Finally, I seek to understand this watershed moment in more nuanced ways by examining how performances of normative masculinity across different cultural contexts manifested in political encounters. Diana Taylor’s concept of scenario is useful in reading these encounters as political theater, in which the body is another way power played out. Following an outline over a script, scenario is a form of “physical theater that is open to variation and surprise even as it is rooted in convention,” a “movable set of prescriptions for body and affect,” and a “range of performative and narrative gestures.” 13 My reading of photographs of the intimate encounters between Mao, Zhou, Newton, and Nixon foregrounds how male homoeroticism is visually conveyed in routine and ceremonial bodily gestures like handshakes and gazes, which become sites of power.

Additionally, Joseph Roach’s distinction between the celebrity’s mortal “body natural” and the immortal “body cinematic” is useful for reading images whereby “these double-bodied persons foreground a peculiar combination of contradictory attributes” such as the “simultaneous appearance of strength and vulnerability in the same performance, even in the same gesture.” 14 In these situations, Newton struggled with addiction and paranoia, Mao was approaching death, and Nixon seemed destined to be a one-term president. All needed to perform strength for the camera. A handshake or gaze on film is fraught with contradiction between natural and cinematic bodies. I read photographs of political encounters as theater with a focus on aesthetics, symbolism, and images and comportment of the body. 15

Mao’s Strange Bedfellows

For all three men, quests for stardom, fears of failure, and desire for legacy associated with masculinity partially propelled their political trajectories, which were the product of more than the rational, strategic planning of organizations, political parties, and states. With his image on posters and in the Black Panther, Newton was the party’s charismatic leader, making his image and reputation crucial to its masculine culture and legitimacy. By the time of the trip to China in 1971, the Panthers faced an irreversible crisis of organization while Newton faced one of image. By Newton’s prison release in 1970, countless Panthers had been killed, imprisoned, or faced trial while state repression was unrelenting. The internecine conflict between the factions under Newton and Cleaver withered the party’s national base; eventually, Newton expelled the entire international branch under Cleaver’s leadership in April 1971. 16 Simultaneously, Newton’s reputation eroded due to cocaine and alcohol addiction, the seduction of stardom, and an intensification of misogynist behavior, megalomania, and authoritarianism. 17 As W.E.B. and Shirley Du Bois, Paul Robeson, and Robert F. and Mabel Williams, and other twentieth century black radical leaders had traveled to China, Newton’s trip was imbued with this rite of passage. China offered a ritual remaking of his image as revolutionary leader.

Above all, Newton wanted to beat his foremost enemy to China. Brown recalls Newton saying, “Nixon has announced he’s going to China! He’s issued some kind of fucked-up statement about opening up avenues of diplomacy – meaning trade, of course. I have to get there before Nixon! …When’re we leaving?!” 18 Newton pens in his memoir, “I decided to beat him to it. My wish was to deliver a message to the government of the People’s Republic and the Communist Party, which would be delivered to Nixon when he made his visit.” 19 As Newton and the Panthers performed an emboldened black militant masculinity as the antithesis of national subjugation, beating Nixon there would undercut Nixon’s distinction as the “first” to reach China, and would help Newton regain his masculine stature. It is also no coincidence that Cleaver had visited China with Brown the previous year, entangling the desire to reach China with the hostile rivalry between not one but two men, and an erotic triangle involving Newton’s romantic partner, Brown.

Facing his presidency’s dismal unpopularity in 1971, Nixon urgently needed a comeback. While the trip to China had been in the making with Henry Kissinger since his inauguration, it took on new importance with reelection at dire risk. On the eve of the trip, Kissinger authored a secret memo, “Your Encounter with the Chinese,” and assured Nixon, “The drama and color of the state visit will surpass all your others.” 20 In his memoir, Nixon includes personal notes written in China: “An election loss was really more painful than a physical wound in war. The latter wounds the body – the other wounds the spirit.” 21 Given China’s involvement with the untenable war in Vietnam, imperial legacies were conflated with presidential ones, such that Nixon wanted “one more victory than defeat” and preferred to be a “one-term president of a first rate power rather than a two-term president of a second rate power.” 22 Thoroughly lacking the charismatic masculinity embodied in his rival John F. Kennedy, foreign policy provided a realm for Nixon to display aspects of normative masculinity. He confessed in his memos “Foreign Policy = Strength” and “Must emphasize – courage, stands alone … knows more than anyone else. Towers above advisers, world leader.” 23 What Nixon lacked in masculinity he translated into a pursuit for greatness in the realm of foreign policy. In going to China, he had much at personal stake, too: injury, fear of loss, and a longing for legacy are also central to the story.

Just as Nixon desperately needed a media diversion to win reelection, Mao needed to “save face” within the party and the country in the wake of scandal over Lin Biao, Mao’s successor and “closest comrade in struggle” who mysteriously died while fleeing the People’s Republic of China for the Soviet Union after his followers attempted a coup d’état. Given the political culture of devotion within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Lin’s betrayal was unthinkable, and led ordinary people to question Mao’s judgment and leadership. Devastated and melancholic, Mao retreated from urgent domestic issues for a year and refused to appear in person before the public while his physical health also deteriorated. 24 In the aftermath of Lin’s death, Mao cancelled many National Day events in early October for a remarkably low-key celebration, which was the condition for inviting the Black Panther Party. 25 Keenly aware of Mao’s vulnerability, Kissinger wrote to Nixon that “the mysterious events last fall and the alleged Lin Biao challenge underline the great gamble Mao and Chou have taken in dealing with us and inviting you. Thus they will need to show some immediate results for their domestic audience.” 26 Far from the stature he once commanded, Mao’s masculine image as divine national leader was considerably diminished.

China was symbolically important within dominant Cold War and black radical imaginaries, but was also a stage for spectacular comebacks for these men. Considering that most Americans reviled “Red China” and those who traveled to China were few and far between, the reception by their nation’s foremost enemy would confer a revolutionary stature once again to Newton and the Black Panther Party. For Nixon, the repossession of a “lost,” or similarly the opening of a “closed,” feminized China would convince American voters of his foreign policy talent and distinguish him from all other presidents. Mao, like Nixon, needed a major triumph on the world stage in order to shore up a crisis of moral authority and reinstate national and CCP confidence in his leadership, and having the premier global power knocking on China’s door for peace was the perfect opportunity to remake his image. From China’s perspective, welcoming these foremost archenemies seems unexpected. By provincializing these historical actors through their interior lives, a narrative emerges in which the making of these trips were driven not purely by the imperatives of political organizing and state-building, but also by personal desires to regain masculinity. These personal desires also played out in performing their masculine subjectivities in the political theater of China for the camera.

- “Huey P. Newton … Returns from the People’s Republic of China,” Black Panther, October 16, 1971, 11.[↑]

- See Robeson Taj Frazier, The East Is Black: Cold War China in the Black Radical Imagination (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015); Judy Wu, Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism, and Feminism during the Vietnam Era (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013).[↑]

- Quoted in Sean L. Malloy, “Uptight in Babylon: Eldridge Cleaver’s Cold War,” Diplomatic History 37, 3 (2013): 566. [↑]

- Erica Edwards discusses “Great Man Leadership” in Charisma and the Fictions of Black Leadership (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), xv. Also see Dayo F. Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodard, eds., Want to Start a Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle (New York: New York University Press, 2009); Carole Boyce Davies, “Sisters Outside: Tracing the Caribbean/Black Radical Intellectual Tradition,” Small Axe 13, 1 (2009): 217–28; H.L.T. Quan, “Geniuses of Resistance: Feminist Consciousness and the Black Radical Tradition” in Race Class 47 (2005): 39–53; Kate Baldwin, Beyond the Color Line and the Iron Curtain: Reading Encounters between Black and Red, 1922–1963 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002). More pertinent to Afro-Asia, see Diane C. Fujino, Samurai among Panthers: Richard Aoki on Race, Resistance, and a Paradoxical Life (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012).[↑]

- Edwards, Charisma, 16.[↑]

- Ibid., 21.[↑]

- Ibid., xv.[↑]

- Michelle Ann Stephens, Black Empire: The Masculine Global Imaginary of Caribbean Intellectuals in the United States, 1914–1962 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 14.[↑]

- Among many excellent essays in this anthology, see Claudia Tate, “Race and Desire: Dark Princess: A Romance,” in Next to the Color Line, ed. Susan Gillman and Alys Eve Weinbaum (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007). [↑]

- Daryl J. Maeda, Chains of Babylon: The Rise of Asian America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 95.[↑]

- Frazier, The East Is Black, 12.[↑]

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 25.[↑]

- Edwards, Charisma, 17.[↑]

- Joseph Roach, It (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007), 36.[↑]

- The abundance and richness of sources from the Nixon-Mao encounter more readily demonstrate the embodied and gendered aspects of these encounters. I have had to speculate with the more limited Panther archive of the Newton-Zhou meeting.[↑]

- Jennifer B. Smith, An International History of the Black Panther Party (New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1999), 54.[↑]

- For accounts of Newton during this time, see Hugh Pearson, The Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America (Reading: Wesley Publishing Company, 1994); Russell Shoats, “Black Fighting Formations: Their Strengths, Weaknesses, and Potentialities,” in Liberation, Imagination, and the Black Panther Party: A New Look at the Panthers and Their Legacy, ed. Kathleen Cleaver and George N. Katsiaficas (New York: Routledge, 2001).[↑]

- Elaine Brown, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story (New York: Pantheon Books, 1992), 296.[↑]

- Huey P. Newton, Revolutionary Suicide, with J. Herman Blake (New York: Penguin Books, 2009), 349. [↑]

- Henry Kissinger to Richard Nixon, “Your Encounter with the Chinese,” February 5, 1972, 1. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 70, eds. William Burr with Sharon Chamberlain, Gao Bei, and Zhao Han, May 22, 2002, http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB70/doc27.pdf. Material originally sourced from the Nixon Presidential Materials Project, Nixon Presidential Library, Yoruba Linda, California.[↑]

- Richard Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978), 573.[↑]

- Nixon: The Presidents Collection (WGBH Boston, 1992), http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/nixon/.[↑]

- David Greenberg, Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2003), 272.[↑]

- Philip Short, Mao: A Life (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2001), 539; Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao, with Anne Thurston, trans. Tao Hung-chao (New York: Random House, 1994), 542; Ross Terrill, A Biography: Mao (New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1980), 353.[↑]

- Because accounts of the Panthers’ trip to China are scarce, I quote from secondary sources at length. Terrill’s account is especially revealing: “National Day 1971 passed in an eerie atmosphere. There was no giant parade – for the first time in the history of the PRC – and Mao was still out of sight. Grandstands had been erected in early September, ready for the parade and the viewing of National Day fireworks. In mid-month they were speedily dismantled. Low-key festivities unrolled in the parks. Zhou appeared at midday to escort Prince Sihanouk on a boat trip at the Summer Palace. Three American Black Panther leaders were there, and a French chef … But few of the Politburo. Mao was present only in the form of huge blowup photos … People’s Daily did not offer it usual celebratory editorial on October 1. Nor a picture of Mao and Lin together (the ultimate in political photography during 1970–1971). Some people inside China as well as outside though Mao was dead – or gravely ill.” Terrill, A Biography: Mao, 350–51.[↑]

- Henry Kissinger to Richard Nixon, “Your Encounter with the Chinese,” 2. Throughout this article, I include both variations of spelling (e.g., Mao Zedong and Mao Tse-Tun, and Zhou Enlai and Chou En-lai).[↑]