Out of the Archive

Invited by the Friendship Association, in late September 1971, Newton, Brown, and Bay traveled to China for ten days to deliver the “People’s Petition” that called for “the peace-and-freedom-loving Chairman Mao Tse-Tung to be the chief negotiator to Mr. Nixon for the peace and freedom of the oppressed people of the world” in the aftermath of the Attica crisis.1 Since the U.S. press had not covered the petition, publicizing it became, according to the Black Panther, the “very reason the visit had been made.”2 Newton and the Panthers did not meet with Mao, but with Zhou. At every stage, from planning to the press conference upon return in San Francisco, Newton underscored the rivalry with Nixon, as if they were on the same level with the Chinese government. Even as he acknowledged that Mao only met with heads of state, he went so far as to suggest that Nixon’s trip was only an “intended visit” and the CCP might decline to accept Nixon after already accepting the Black Panther Party.3 Newton reported meeting applause everywhere from crowds waving Little Red Books and carrying signs that read “We support the Black Panther Party, down with U.S. imperialism” and “We support the American people but the Nixon imperialist regime must be overthrown.” He also described a crowd of a thousand people welcoming the Panthers back at the San Francisco airport and being hounded by a Canadian reporter inquiring if they intended to spoil Nixon’s upcoming trip.4 Imperative to this story, Nixon’s upcoming trip blurred Newton’s view, and eventual representation, of the trip to China.

However, a crucial detail is missing from the Panther archive. In the tradition of official hospitality, Zhou hosted a National Day banquet for a group of U.S. citizens from a variety of political backgrounds. With Nixon’s trip on the horizon, the CCP needed to reorient its friends to a new diplomatic regime, especially those with influence over “middle America” and the left.5 It is no coincidence this detail does not appear in Newton and Brown’s memoirs or in the Black Panther. Foregrounding absences in the archive reveals the gulf between the Panthers’ enthusiasm for China on the one hand and China’s ambivalence over and instrumental deployment of its revolutionary friends on the other hand, which lays bare the sheer unevenness and limits of transnational solidarity.

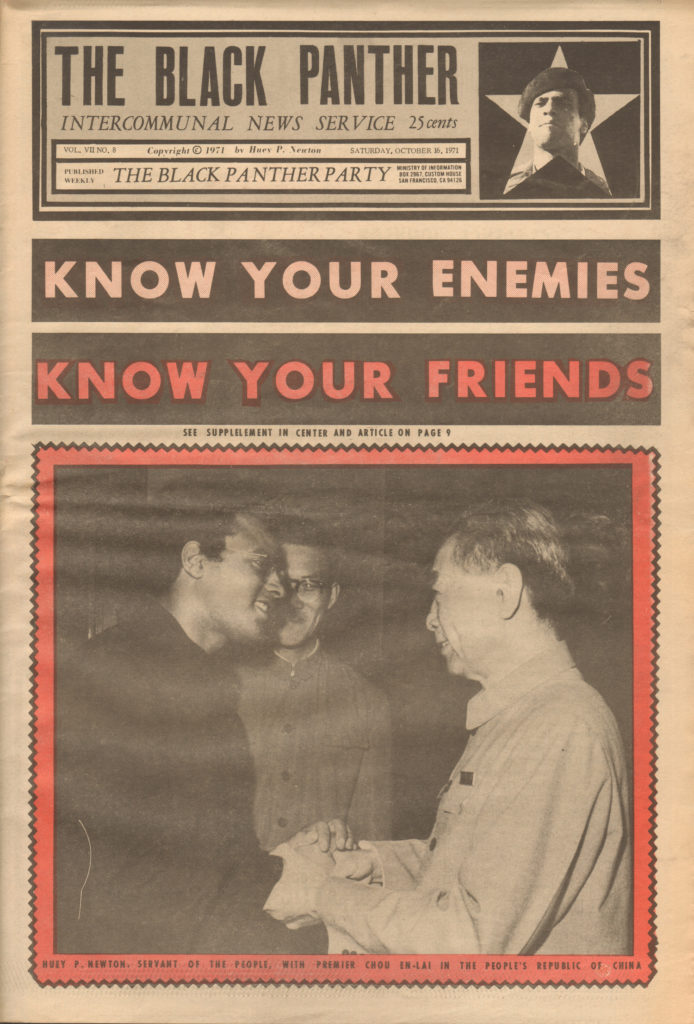

Appearing on the Black Panther‘s cover and featured inside, the iconic black and white photograph of the trip is of Newton and Zhou’s encounter (see figure 2). Eyes locked on each other, they shake hands with both hands, an enthusiastic embodied form of male homosociality coded as cross-racial solidarity. Partially blocked by Newton’s face and shadow, an unnamed CCP official observes and smiles. The three men are dressed in the austere military-style uniforms of the Cultural Revolution era, bestowing a revolutionary authenticity within the aesthetics of socialism and “Chinese puritan communism.”6 Yet the image is far from a carefully staged photograph of leaders standing together: Zhou’s face is obstructed, as is a second CCP official who is looking at Newton and diverted away from the camera.7 The poorly staged image suggests there were existence of only a few images of a fleeting encounter. The scenario Newton desired did not unfold as expected.

Before the press, when asked how Zhou would support the Panthers, Newton responded, “Premier Chou En-Lai said many things to me; but I will not comment on specifics.” When asked how long they spoke, Newton tersely said, “No comment on that.” When pressed again to elaborate on outcomes of his visit with Zhou, he quite tellingly responded, “There’s a phrase in the Black Panther Party that a picture is worth a thousand words; and, of course action is supreme … Of course, we have the picture. You can tell by the picture that we were very well received. (We’ll pass the photographs afterwards.)”8 The image becomes a smokescreen in front of what failed to transpire.

Importantly, Brown and Bay do not appear in the frame, enabling Newton to be the star of the capstone photograph. As she recalls in her memoir, at the time of the trip Brown, “Huey’s Queen,” was the “most important woman in the party,” second only to Newton because internecine factions eliminated other male leadership such as Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver.9 Brown cannot be in the frame to detract from Newton’s stardom and the saturated homosocial desire between Newton and Zhou. Photography and political spectacle have historically been important in perpetuating charismatic male leadership, which centralizes the black masculine body as an ideal for other men to desire.10 For this reason, Bay’s body cannot be in the photograph either, as it would detract from Newton’s. The photograph evokes desire for Newton’s body, the only one featured in the image, reasserting his militant masculinity.

Afro-Asian solidarities were uneven not only in their transnational engagement, but also in relation to gender hierarchies. Panther women in the rank and file were integral to the party’s daily operations even as the leadership assumed a masculine public identity. Overt and covert power struggles and nuanced contradictory realities around gender played out in the everyday: between media image and everyday praxis, rhetoric and reality, theory and practice, and rank and file and leadership.11 These dynamics also played out in the trip. Brown recalls that “Huey had suddenly ordered me to arrange a trip to China for him and me,” with Bay joining as a bodyguard on short notice to appease Newton’s paranoia of being watched. Having traveled to China with Cleaver in 1970, Brown undertook the taxing work of arranging the logistics with the embassy and a travel agency, and providing emotional support for Newton. Stateside, June Hilliard arranged the press conference, and Brown wrote “Huey’s press statement” on the airplane to San Francisco. Ironically at the press conference, at the last minute Newton asked her to read the statement as the newly elected Minister of Information as a gesture toward gender equality they had witnessed in China.12

Despite Newton’s equalizing gestures, the charismatic male leader prevailed. Akin to charisma, “glamorous celebrity must be exercised effortlessly or not at all but, paradoxically, that effortlessness requires considerable effort.”13 Brown and Hilliard’s unrecognized labor made Newton’s stardom possible. As Edwards critiques, charisma enacts a historiographical violence of naturalizing male leadership, which in the interest of exalting a select few male actors, elides the historic roles of women like Brown. To return to the press conference photograph, Brown is cropped out of image in the Black Panther, the official party archive, in spite of her contributions. Only through examining Brown’s memoir does women’s less-documented organizing labor come to the surface. The feminist queer intervention in Afro-Asian studies is not necessarily “contributionist” limited to recuperating Brown’s role, but rather makes visible structures that reproduce normative masculinity that relegated Brown’s visionary leadership to being “Huey’s Queen,” never a “brother.”

Aesthetics, Bodies, and Politics

In the first major diplomatic event of the age of global telecommunications, Nixon and his aides engineered the trip to China as an eight-day miniseries including primetime specials and live coverage that strategically occurred when viewer levels were at their peak.14 Television was a powerful medium for rehabilitating Nixon’s image by invoking the figure of the Western hero, a cultural icon of white American masculinity, through canonical tropes of discovery, adventure, and romance in “strange” or “dangerous” places on an extraordinary transpacific voyage.15 Just as Newton recognized the power of an image, Kissinger remarked, “Pictures overrode the printed word.” Any criticism against Nixon was eclipsed by the “spectacle of an American president welcomed in the capitol of an erstwhile enemy.”16 Nixon’s team masterfully timed the flight such that his carefully rehearsed egress from the plane, among the most important images of the entire trip, was broadcasted in the evening during his favorite time for televised speeches.17 Nixon and the first lady descended from the plane while his entourage remained inside in order to focus attention on the “Commander in Chief as superstar.”18 Nixon then proffered his hand to Zhou Enlai for the cameras, recounting at length:

Chou En-lai stood at the foot of the ramp, hatless in the cold. Even a heavy overcoat did not hide the thinness of his frail body. When we were about halfway down the steps, he began to clap. I paused for a moment and then returned the gesture, according to the Chinese custom. I knew that Chou had been deeply insulted by Foster Dulles’s refusal to shake hands with him at the Geneva Conference in 1954. When I reached the bottom step, therefore, I made a point of extending my hand as I walked toward him. When our hands met, one era ended and another began.19

Nixon’s meticulous detailing of postures, gestures, and dress suggests how historic struggles for power were carefully performed through the symbolic theatrics of the body, whereby he was aware of not only his body, but also Zhou’s. Additionally, scenarios are historically layered, as Dulles was a specter for Nixon. In another instance, Nixon divulged in his diary that Mao “couldn’t be in a position of my seeing him in a way that put him above me, like walking up the stairs or him standing at the top of the stairs.”20

Mao also paid great attention to bodily comportment and power. According to Mao’s physician, Mao, gravely ill and bloated, went to great lengths to look presentable to Nixon and the press, which included practicing sitting down and standing up and hiding emergency medical equipment in the meeting room. Despite his failing health and reclusive melancholia, his physician observed that “Mao was as excited as I had ever seen him the day Nixon arrived.”21 In a self-aware statement, Mao quipped to Nixon during their meeting, “Appearances are deceiving.”22

Homosocial desire figured in these encounters, signaling not solidarity but diplomacy. Emphasizing the careful enactment of the handshake, Nixon wrote, “probably the most moving moment, when he reached out his hand, and I reached out mine, and he held it for about a minute.”20 The handshake’s duration was startling and memorable, attesting to how it exudes homosocial desire. Furthermore, the trip’s capstone was a homoerotic scene saturated with tension. With the exception of a female interpreter, Mao, Zhou, Nixon, Kissinger, and Winston Lord gathered in Mao’s bedroom. Their meeting appeared cordial, yet power struggles were covertly unfolding. Exerting his power over media coverage, Mao allowed only Chinese photographers in the room.23 In the key photograph that graced the covers of newspapers, Nixon tensely and earnestly leans in toward Mao, who is relaxed in posture and quietly triumphs in the center of the photograph. The least visually engaged actor in the photograph is the interpreter, her eyes averted downward as she is the key interlocutor in this encounter between men.

Redressing the historic power balance manifested not only in extending handshakes, but also in symbolic rituals of Chinese diplomacy. With the aesthetic-political framework in Communist China, Ben Wang remarks, “politics does not borrow the garb of aesthetics to dress itself up but is itself fleshed out as a form of art and symbolic activity.”25 Departing from Western rubrics of masculine norms, Mao’s moves over Nixon were legible within Chinese aesthetics and politics. In the ubiquitous “Mao jacket” associated with the military and proletariat, Mao’s dress contrasted with his suited American counterparts in aesthetic and political registers. Mao placed Nixon in a subordinate position by the very terms of the meeting. As Nixon journeyed across the Pacific and executed his trip, Mao did not leave his home, not even to attend the banquet or policy talks.26 In the image above, their sole meeting was in the desire-laden, innermost space of Mao’s bedroom. For Chinese viewers, Nixon’s journey to Mao’s bedroom signaled the “foreign barbarian” capitulating to the emperor under the traditional monarchy.27 No longer a private sanctuary, Mao’s bedroom was transformed into a political theater of the world’s most powerful men.

Mao also carefully performed masculinity for the camera. Chinese masculinity, which departs from Western ideals of the same, is framed through wen-wu (cultural attainment-martial valor), where wen is associated with the intellect of the literati and wu is associated with the warrior, valuing not brute force but physical skill. Despite wen-wu‘s differences from dominant Eurocentric gender ideals, “in most contexts it enabled educated men to dominate others” and the core of these constructs has remained intact over time.28 In this photograph, Mao’s age, frailty, and engulfment in books exudes strong wu and resonates with the figure of the junzi, a wise sage and gentleman who is an authority figure akin to virtuous, benevolent fathers. The junzi as a model for masculinity is tied to Confucianism, and its role was highly contested in the “New China” and the making of the new socialist man.29 However, the capstone image evokes Mao as junzi and Nixon as the opposite “inferior man” (xiaoren).30 Aesthetics and bodily comportment and images add depth to understanding this watershed moment.

Conclusion

The reproduction of normative masculinity was at the heart of the intertwined trajectories that led Mao, Nixon, and Newton to each other in China, and animated their encounters as struggles for power unfolded through natural and cinematic bodies. Because much has already been written about all three men, Nixon’s trip to China, and Panther internationalism, I have taken some creative license and a more playful approach in which I speculate on the interior and subjective forces that also motivated these key historical events. In so doing, I proffer a way of working with archives that center “Great Men” while interrogating and destabilizing their roles as historical actors. By finding disconnects across sources and narratives, I expose the messiness and unevenness of these encounters elided in the service of nostalgic, romantic renderings of historic solidarities. In this instance, solidarity was not fully realized. Part of the feminist queer intervention is to interrogate what is written in and out of the archive, and to what ends. These occlusions are related to hierarchies and norms around gender, race, and sexuality and the reproduction of normative masculinity and heteropatriarchy, particularly through charisma and the depiction solidarity as male homoeroticism.

Revising the history of this conjuncture offers lessons about Afro-Asian solidarity. Despite surface appearances, politics play out in nuanced ways that are not always legible in speeches and communiqués, and require different ways of reading, such as realms of affect and intimacies where subtle power dynamics take shape. Nixon’s meeting with Mao was indeed history making, but it was not entirely a triumph of U.S. imperial capital hegemony over China. Nixon was beholden to Mao in these crucial moments. For Newton and the Panthers, their trip was far less successful than they depicted. They were only invited to assist with Nixon’s meeting with Mao, and Mao did not present the Panthers’ demands to Nixon. Solidarities and imperial diplomatic projects, as this conjuncture shows, were much more fraught than they appeared.

There are some lessons here for future Afro-Asian solidarities. As the image of the encounter between Zhou and Newton demonstrates, solidarities were fleeting, but the ephemeral nature of solidarity does not necessarily suggest failure. Attending to the contestations between men reveals the contours of gender, sexuality, and desire in mediating solidarities and is generative in thinking about the possibilities and limits of solidarity politics through the intimate and modes of affect. The intimate and affective is an unexpected place for Afro-Asian world-making, even if those relational ties and solidarities are fraught and fleeting.

- “Know Your Enemies, Know Your Friends,” Black Panther, October 16, 1971, B–C. [↩]

- “Huey P. Newton … Returns,” 9, 11. [↩]

- Ibid., 10; Newton, RS, 352. [↩]

- Newton, RS, 349, 351 [↩]

- As Anne-Marie Brady retells: “On 5 October 1971 Zhou Enlai hosted a special reception at the Great Hall of the People for a large group of U.S. citizens. People from a wide range of political backgrounds were invited to attend, and all expenses for their trip in China were paid for by Beijing: members of the Black Panthers were there; as were delegates from an American youth group … Zhou Enlai explained to the group that Nixon was to come to China and why this was so. He asked them to help promote the friendship between the United States and China and to work to improve China’s image there … The reception was part of the buildup to Nixon’s visit to China, and was emblematic of the beginnings of Sino-U.S. rapprochement.” Anne-Marie Brady, Making the Foreign Serve China: Managing Foreigners in the People’s Republic (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2003), 180–82. [↩]

- Bin Zhao quoted in Tina Mai Chen, “Dressing for the Party: Clothing, Citizenship, and Gender-Formation in Mao’s China,” Fashion Theory 5, 2 (2001): 146. [↩]

- In a similar photograph in which Mao and Nixon meet and shake hands, the Chinese airbrushed out Mao’s personal secretary who stood between them. In this genre of diplomatic photograph, the image must center two, and only two men, joined through a handshake. Mao meets Nixon, photograph, 21 February 1972, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book no. 66, ed. William Burr, 27 February 2002, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB66/bcp03.html. Material originally sourced from Nixon Presidential Materials Project, Nixon Presidential Library, Yoruba Linda, California. [↩]

- “Huey P. Newton … Returns,” 10–11. [↩]

- Brown, A Taste of Power, 298. [↩]

- Edwards, Charisma, 43. [↩]

- See Tracye A. Matthews, “‘No One Ever Asks What a Man’s Role in the Revolution Is’: Gender Politics and Leadership in the Black Panther Party, 1966–71,” in The Black Panther Party Reconsidered, ed. Charles Jones (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1998), 233. [↩]

- Brown, A Taste of Power, 295–96, 304. [↩]

- Nigel Thrift, “Understanding the Material Practices of Glamour,” The Affect Theory Reader, ed. Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 304. [↩]

- Edward Berkowitz, Something Happened: A Political and Cultural Overview of the Seventies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 41. [↩]

- Richard Madsen, China and the American Dream: A Moral Inquiry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 69, 73. [↩]

- Berkowitz, Something Happened, 42. [↩]

- Rick Perlstein, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (New York: Scribner, 2008), 624. [↩]

- David D. Perlmutter, Picturing China in the American Press: The Visual Portrayal of Sino-American Relations in Time Magazine, 1949–1973 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007), 196. [↩]

- Nixon, RN, 559. [↩]

- Ibid., 560. [↩] [↩]

- Li, 562. [↩]

- Nixon, RN, 564. [↩]

- Margaret Macmillian, Nixon and Mao: The Week that Changed the World (New York: Random House, 2007), 70. [↩]

- The Mao-Nixon meeting, photograph, 21 February 1972, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book no. 66, ed. William Burr, 27 February 2002, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu//NSAEBB/NSAEBB66/bcp04.html. Material originally sourced from Nixon Presidential Materials Project, Nixon Presidential Library, Yoruba Linda, California. [↩]

- Quoted in Chen, “Dressing for the Party,” 146. [↩]

- Terrill, A Biography, 358. [↩]

- As John Fairbank writes about the Chinese patriarch under Confucian monarchy, “The Humble Submission of the Foreigner Came in Direct Response to the Imperial Benevolence, which Was Itself a Sign of the Potent Imperial Virtue.” John King Fairbank, Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast: The Opening of the Treaty Ports, 1842–1854 (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1969), 25–8. [↩]

- Kam Louie, Theorising Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China (Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 4, 161; Kam Louie, “Popular Culture and Masculinity Ideals in East Asia, with Special Reference to China,” Journal of Asian Studies 71, 4 (2012): 939. [↩]

- Stefan Landsberger, Chinese Propaganda Posters: From Revolution to Modernization (New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1995), 26. [↩]

- See Kam Louie, “Sage, Teacher, Businessman: Confucius as a Model Male,” Chinese Political Culture, 1989–2000, ed. Shiping Hua (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2001), 21–33. [↩]