This interview was conducted over email from July through October, 2008.

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

DJ Spooky, trailer for Terra Nova: Sinfonia Antarctica

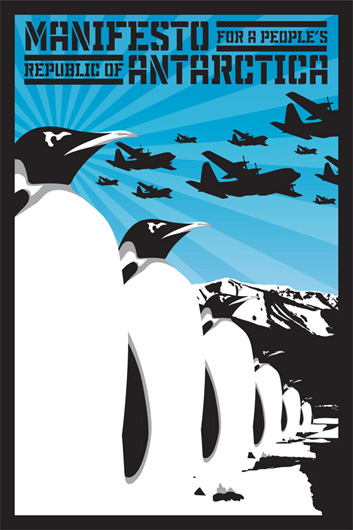

You recently completed two multimedia projects: the film Terra Nova: Sinfonia Antarctica, and “Manifesto for a People’s Republic of Antarctica,” a gallery installation (at Robert Miller Gallery and Irvine Fine Arts). Both projects incorporate field recordings and audio samples from your visit to Antarctica, mixed with electronic beats and other visual materials. How did your conception of Antarctica as a place interact with your embodied presence? What was the most surprising aspect of being in Antarctica?

We chartered a boat, a Russian ice breaker called “The Academic Ioffe,” and traveled there by way of South America. We went to several islands and ice fields that were near the Antarctic peninsula but a little further down on the continent. I’ll be going back in a while to check out more of the interior. The next time I go, I’m going to try and get to the Lake Vostok base.

The most surprising thing about Antarctica was the stench of penguin shit. You can smell it a mile or so out in the water! I’m always “embodied” (I always tend to mix that up with “embedded” these days anyway), so there wasn’t the conflicted sense of spatial issues that seems to haunt a lot of the discourse about what physical performance is all about in a digital context. I live and remember it all.

How do you see your mixed modes of approach—embodiment and digitized representation—in the context of the history of representing the (arguably) most mediated place on earth?

Everything I do is about paradox, paradox makes life fun. I think that people need to “hear” Antarctica because it is at the edge of the world. The phrase “mixed modes of approach” is a good one . . . of course, the dominant theme in DJ culture is “the mix,” so there are some salient linkages there. The technical terms “heterodoxy” or “heterogeneity” both find a solid home in me and my work; I celebrate that kind of thing. One day, a software we use and the life we live will blur. It’s kind of already happened. But that’s why I go to places like Antarctica.

Take New York City for example. If I have a conversation at a café, someone will put it on a blog. If I walk down the street, someone puts photos of it on flickr. It’s irritating, but hey . . . it’s the way we live now. You could argue that New York City is probably one of the most mediated places on earth. Antarctica represents a place mediated by science—it’s literally almost another world. Some of my favorite science fiction books, like Kim Stanley Robinson’s Antarctica and Crawford Kilian’s IceQuake, deal with some of the same themes: science, art and the weird un-worldliness of the ice terrain. My Terra Nova and “Manifesto for a People’s Republic of Antarctica” projects are in the same tradition. Music from the edge of the physical environment and music from the core of the urban landscape: Watch them collide in paradox.

How did Antarctica emerge into your world? Was it through images? Fiction? Or the study of historic exploration figures?

I used to watch old films whenever I could, and some of my most formative film experiences were George Méliès’ 1902 The Conquest of the North and Frederick A. Cook’s 1912 The Truth About the Pole. These two films are about the opposite side of the planet from Antarctica, but there’s a kind of strange dualism to them that was really influential. Like the Lumiere brothers, Cook’s film tried to portray itself as realistic, almost like a documentary. Méliès, on the other hand, started out as a magician who wanted to apply magic technique to film. The two films are so different, but they’re both amazingly, eerily prescient about how discovery and the “voyager’s path” would then take on almost surreal proportions.

There’s a similar motif that runs through my Terra Nova and “Manifesto for a People’s Republic of Antarctica” projects. They both use found footage, print-design, and propaganda to show how exploration at the edge of the world is a prism to view how nations look at one another, and how art itself is a highly politicized medium. I guess you could say I’m inspired as much by the scene in Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, where Captain Nemo sails his submarine to the Antarctic sea shelf, as I am by the film 90 Degrees South by cinematographer Herbert G. Ponting, who was one of the first people to get footage from Antarctica.