Art (Click images below to enlarge)

Article about the Artist

This article was originally published in Nancy Campbell’s Annie Pootoogook, published by Illingworth Kerr Gallery in Calgary and Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown in 2007. It is reprinted with permission.

Inuit Art and the Limits of Authenticity

by Debora Root

Several years ago I purchased a print by Cape Dorset Pudlo Pudlat entitled Imposed Migration (1986). In this image three animals dangle by their necks as they are carried away by a military helicopter. As I gazed at the polar bear ensnared by the noose around its neck, the gallerist explained that Inuit work depicting contemporary objects, such as snowmobiles or helicopters, was very much a minority taste. Most buyers preferred the sublime images of the natural world and traditional ways of life that Southerners have come to associate with Inuit art, she said, because there are more authentically and recognizably “Inuit.” For such buyers, authenticity resides in what is sometimes termed the “ethnographic present,” a timeless place untainted by modernity.

Twenty years later, there would seem to be more openness to the contemporary images explored by some Inuit artists. Exhibitions of Annie Pootoogook’s work at the Illingworth Kerr Gallery, Documenta in Kassel, Germany and The Power Plant, Toronto, and her recent 2006 Sobey Art Award, suggests that Inuit art is beginning to be understood as a vital aesthetic practice rather than a static, culturally determined artifact. That the pace of Inuit art within the art world remains a topic of discussion indicates the persistence of older ideas of what this work is or should be. And many Southerners continue to believe that images of a pristine Arctic are somehow more authentically Inuit than Pudlat’s machines or Pootoogook’s video games.

Within a contemporary art paradigm, however, “authenticity” means something rather different. Here, disturbing images tend to be seen as more “real” than beautiful ones, in part because the artist’s job is to strip away the dishonesty and pretension of modern society. Think of Warhol’s car crashes; think of all the recent work that seeks to shock the viewer into a different way of apprehending the world.

“Authenticity” is a floating category, able to migrate and legitimize or de-legitimize certain kinds of images. If some consider Inuit art inauthentic when it includes recognizably Southern elements, others have suggested that the art is itself inauthentic because it is a constructed tradition. No art market existed in the North prior to James Houston’s efforts to create one in the 1950s and 60s. The argument can be reduced to something like this: white impresario travels North with a plan; the work is marketed in the south as “authentic,” even if there was no pre-contact tradition of large-scale sculpture or printmaking. The work is purchased primarily by those seeking an idealized representation of First Nations experience. Meanwhile, colonialist structures and institutions remain, masked by images of a pristine past. 1

Of course, what is missing from this formulation is the work itself. In this view, Inuit art cannot be an “authentic” expression of an artist’s aesthetic vision because it is market-created (unlike the New York art world, one assumes). It is bad enough that a concept of inauthenticity is sometimes used to de-legitimate Northern art practices, but we would do well to remember that this category has also been employed within the Canadian and U.S. legal systems to undermine Fist Nations’ land claims. At times the authentic is used to denote a traditional way of life or quality than someone thinks should be retained, and at other times it is used to suggest a gritty contemporary quality. The question always remains of who is deciding what is genuine.

The history of the Inuit image-making, and its reception in the South, thus raises questions about what kinds of images come to be valorized in the Southern marketplace, and about the cultural and aesthetic expectations n the part of consumers. Printmaking and soapstone carving originally were designed to bring Northern communities into a cash economy, and to generate images that would stand for the Canadian identity in the international area. Because Southern buyers wanted access to another world, traditional images sold well.

In this sense it is true that Inuit art is a constructed tradition. Yet Inuit drawing, printmaking and soapstone carving quickly exceeded the bare fact of their origins, and became conduits through which Northern artists could express aesthetic and social concerns in new and meaningful ways. The constructed traditional became real through the lived experiences and aesthetic practices of the artists. And because Northern society exists in the present, some Northern artists make images of contemporary realities.

But the reception of Inuit art in the South has been slower to transform. Until very recently, Inuit art remained in a category by itself, a subset of First Nations art, not quite traditional, not quite modern, and rarely understood as contemporary. Southern buyers of Inuit art tended not to follow contemporary art; similarly, those interested in contemporary art were relatively indifferent to Inuit art. Inuit art was a separate market, firmly sited in an anteroom of Canadiana and rarely stressed in Canadian art history curricula. Although artists such as Annie Pootoogook are breaking through these categorical strictures, many of the old assumptions remain.

Even if nearly everyone can appreciate the beauty of such work as Kenojuak’s iconic Enchanted Owl (1960), there has been a tendency in contemporary are circles to dismiss Inuit art as something akin to tourist art. I used to feel slightly sheepish about liking Inuit art; it was something for corporate offices, or Canadian embassies in Europe. I can also understand why many might be disturbed by the mechanized intrusion of Pudlat’s helicopter into the natural world. But, as a contemporary image maker, Pudlat had something to say about the fantasy of an untouched landscape and the reality of Canadian government policies. And utilizing a difficult image to unmask received ideas is something we would expect to encounter from a non-Inuit contemporary artist.

A recent text asserts:

Producing art has enabled many Inuit to pursue a relatively traditional lifestyle . . .. While Inuit artists have been prompted and influenced to produce art by southerners and southern institutions, they have nonetheless managed to imbue their art with traditional values and memories of life as it once was . . .. 2

In one sense there is nothing wrong with these remarks. But, written in 1998, they draw the reader’s attention away from the contemporary context of Inuit image production and towards the past. The reiteration of a notion of the “traditional,” which in fact does not exist in the way many Southerners imagine, becomes a way of manipulating the viewer’s expectations.

Native communities have often been presented, in films and ad copy, as existing in an eternal past or, if attempting to negotiate the present, as somehow more firmly tied to or affected by the past than non-Native communities. Each community has a particular relation to history, and colonial histories in Cape Dorset will differ from those in Toronto, but these specificities ought not be dependent on an unexamined notion of a timeless past. This brings us back to the category of authenticity, and how perceptions and expectations of a traditional, unchanging North are structured.

Part of the problem lies in the way the cultural difference of Inuit society functions to assuage anxieties about change in Southern cultures. If, in the case of the North, “authentic” is believed to mean the pre-contact world depicted in Inuit art, this concept serves to eliminate social space; politics disappear, so there is no necessity for excavating history, there is no responsibility for righting injustices or supporting land rights. There is no guilt. The Southerner can mourn the loss of a pristine natural world without thinking about why this has happened, and without examining how and why similar losses have occurred in the South, and the costs of these for everyone. Within the art works, certain images have come to stand for this cultural difference—a seal hunt, a shaman, a dancing polar bear—which in turn stand for a generalized authenticity. In fact what is being consumed is authenticity, and the consequence of this simulacrum of difference is that we need not ask why these are the images we want to see. But if something is deemed “authentic,” something else must necessarily be inauthentic by comparison.

It is long past time to call into question the familiar, overarching categories that structure our understanding of art, such as Inuit art, outsider art, Northwest Coast art, tourist art, Canadian art, Western art. If we wish to classify art practices, different criteria might be more to the point, in particular a notion of “school,” which suggests a group of artists addressing similar concerns and styles in their work. A contemporary landscape school might encompass works from several origins; what holds the category together is the approach to a subject, not the ethnicity of the artist.

As a category, “Inuit art” is simply too broad, and too culturally determinant, implying a unified aesthetic vision that does not exist even within work that takes traditional life as its subject. For example, the minimalist, early drawings of Luke Anguhdluq utilize white space to convey bareness in the Northern environment, while Simon Tookoomee’s highly colored images burst forth in an exuberant vision of the spirit world. And “Inuit art” is too restrictive a category for the work of Annie Pootoogook, whose contemporary vision transcends older limitations.

The inadequacy of “Inuit art” as a category is apparent in the unease artists such as Pudlat or Pootoogook provoke when they address contemporary issues. In reality, Inuit art has always crossed many categories; at once a pricey souvenir of a visit to Canada and a nationalist symbol in embassies, it often exceeds both these limited expectations. A whiff of the ethnographic remains in some images, but even so, such work rarely falls into kitsch, even in pieces one sees in hotel gift shops. The fact is that Inuit art is often very good, and at times extraordinary, something most of us do not expect from tourist art. The range of the work reminds us that there is no such thing as a pure state of cultural authenticity. Culture has always been mixed, contradictory, difficult.

Pootoogook’s work illuminates many of these issues, reminding us again that one of the reasons people make images is to exemplify the world they inhabit, and to show how this world works in new and unexpected ways. Contemplating Pootoogook’s images of Northern life, the viewer sees that the old, discrete categories “Inuit art” and “contemporary art” are no longer relevant.

As in much contemporary art, there is something profoundly disturbing about her images of the everyday, where the figures seem to float in space as they go about their business. One looks not only because of a fascination with the mix of Northern and Southern elements, but because the images oscillate between anomie and community as they interrogate the individual’s relation to material culture. Some viewers understand Pootoogook’s work as exemplifying a “culture clash” between North and South. For me, this does not quite ring true. Rather than a portrayal of Northern and Southern cultures as separate, isolated entities, what we see in Pootoogook’s images is an integration of elements, an integration characteristic of lived experience. Her work presents culture as a fluid entity, and makes it very clear that Southern elements are being taken up and interpreted actively, rather than by passive recipients or victims of colonialism. Yet that history is there, situated in the sometimes difficult lived culture she depicts, yet by no means ethnographic. And sometimes her vision is ironic, sometimes not.

Contemplating Pootoogook’s images of video games, television, and anxieties about monthly bills, the non-Inuit viewer is confronted with his or her assumptions about life in the North. If those of us who live in the South wish to imagine the North as an essentially natural world, we find it difficult to accept that Inuit societies are in fact modern. Yes, we might recognize that Northerners have Ski-doos and perhaps some canned goods, but when we think of the unspoiled Arctic, Jerry Springer is not what we have in mind. I can’t help but feel that what is at stake is old, colonialist belief in the so-called benefits of civilization. Images of pure, unmediated space allow us to maintain that fiction.

Pootoogook reminds us that everyone enjoys pop culture, and in doing so refuses to allow a paternalistic understanding of life in Cape Dorset. Yet her work also manifests an oscillating unease with the relations between pop culture and the community, the family and the individual, the natural world and machines, and the reality of social problems in the North.

There is a moment near the end of Zacharias Kunuk and Norman Cohn’s film The Journal of Knud Rasmussen (2006) when shaman Avva says goodbye to his spirit helpers. The spirits trudge across the ice, weeping and wailing as they go. Avva has been forced to repudiate the old ways because his starving family will be given food only if they become Christian, which means breaking the taboos that allow spirits to share space. We all feel Avva’s loss, of the past, of an alternative to capitalism, of other possibilities. We want to retain the idea of a place where time stands still, where people live close to the land and remain conversant with a magical world.

Most Southerners encounter Inuit culture through Inuit art, and through the images of traditional hunting, old stories, and shamanism. This is one reason why Avva’s traditional family seems more “real” than the Christian characters with their imperfect English, more authentic, if you will, than the Inuit who have taken on Southern elements. And this brings us back to what we imagine we are consuming when we refuse to accept certain artists’ productions as wholly contemporary, simply because they are made by Inuit.

The Journal of Knud Rasmussen was set in the early 1920s, in a past that from this distance can only be imaginary. Even in Avva’s family, Southern culture was present in the form of made items, and the presence of the Danish anthropologists imply that many of the old ways were already on their way out. 3

As in the South, Inuit communities have changed and continue to change, and this is reflected in the kinds of images produced by Pootoogook, whose subject matter differs from earlier generations of artists, such as her mother Napatchie Pootoogook and grandmother Pitseolak. Inuit communities have engaged with Southern influences for a long time. The idyllic images of hunting and other traditional ways depicted in the first Inuit artworks available in the South exemplified a world that was already under extreme pressure, in many ways no longer existing as it once had even twenty years earlier. It seems likely that a nostalgia for an older way of life was present on all sides, from the artists to the collectors, and there are several reasons why government officials and Southern collectors might wish to see images without political unpleasantness.

But the point is not that the North has changed, but rather that the South must be willing to see in a different way, and to begin to accept Inuit artists as artists, without expectation of particular kinds of images or a pre-determined cultural authenticity. If we delegate the loss of the natural world to Avva, or to the past, or to Inuit artists who are supposed to heal us with sublime images of nature, then we are dooming ourselves to a false relation to the world. It seems evident that contemporary art is almost by definition a hybrid form, whether the artist comes from Toronto or Cape Dorset. The Illingworth Kerr Gallery’s presentation of Annie Pootoogook’s work marks an important beginning of this shift in perception.

Statement About the Artist

This article was originally published in Nancy Campbell’s Annie Pootoogook, published by Illingworth Kerr Gallery in Calgary and Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown in 2007. It is reprinted with permission.

Annie Pootoogook

by Nancy Campbell

As I stood in the grand reception room of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Montreal and heard Annie Pootoogook’s name announced as the winner of the 2006 Sobey Prize, I reflected on what it was about her that had captured the contemporary art world’s attention. The Sobey Prize, awarded to a promising Canadian artist under forty, represents a significant marker of who in Canada is making art that demands attention. Winning the prize is especially significant for an Inuit artist, because the region of Nunavut (or the Canadian Arctic in general) was not included in the jury’s consideration prior to this year’s competition. As curator of the Annie Pootoogook exhibitions, I clearly believe Annie Pootoogook’s work is significant; it gently rests at an important historical juncture, bridging tradition and ever-changing everyday life. As with much contemporary art, in Pootoogook’s work we see how the local and the global are enfolded, adapted and adopted to produce many different effects. My delight at her winning the prize was great, as it validated, at least for some, her contribution within a national contemporary art context and captured a moment in Canadian art history when “Inuit art” was not segregated as a separate entity.

Cape Dorset in Nunavut is a stunning yet desolate place, set on the rocky coast of Baffin Island where Hudson’s Bay falls into the sea. Being above the tree line, the landscape has a sort of harsh tranquility. In Inuktitut, the language spoken in Dorset, there are at least twenty words for snow and one can see why: in April the ground is still completely covered with snow. Through my conversations with many artists I came to realize that the land is still the life force with the Inuit. For all the signs of adaptation to Southern comforts—as evidenced by the brand new Co-op Food Store that carries produce such as pineapple and portabello mushrooms, and the availability of television and broadband—the culture retains a very strong connection to the traditional lifestyle of living on the land. In the summer months, families go out on the land for weeks at a time, hunting game such as caribou, seal, walrus and bear. Some sleep in tents outside their “southern style” three-bedroom houses while the weather is nice.

Since the founding of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative in the 1950s, Cape Dorset has been the centre of Inuit art activity. Renowned artists such as Pudlo Pudlat, Kenojuak Ashevak and Napachie Pootoogook have mapped a history for artistic production in the region through the Co-op and the Cape Dorset Print Collections. These elder artists grew up on the land and their work typically records and reflects the traditional Inuit way of life. This style is synonymous with what the South perceives Inuit art to look like.

Born in Cape Dorset in 1969, Annie Pootoogook is the daughter of artists Napachie and Eegyvudlu Pootoogook and the granddaughter of the celebrated artist Pitseolak Ashoona.

I used to go and see my grandma drawing because I wanted to learn and she was my grandma. Nobody used to watch her. I don’t know why. I wanted to learn, so I had to watch her. So she talk . . . she used to talk to me and say, my grandma used to say, “I’m drawing because my grandchildren have to eat.” But she drew a true story, too, about her life. Sometimes she talking to me what they’re doing about life in the past. But she used to tell me, “You should try when you grow up, if you can.”

Annie began drawing in 1997 with the encouragement and support of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative. The Co-op remains a distributor for the artists in the community, providing them with studio space and materials, buying their work, and promoting it in the South. In many ways the idealistic notion of the artist and the creative spirit is highly mediated through economics. Because art-making is the main economy in the community, discussion of artistic practice often takes place in these terms.

Drawing makes me very happy more than anything. If I didn’t start drawing I imagine I would be hungry, on welfare . . . welfare for long months. But the drawing doesn’t make me hungry or . . . I always have something to buy with the drawing.

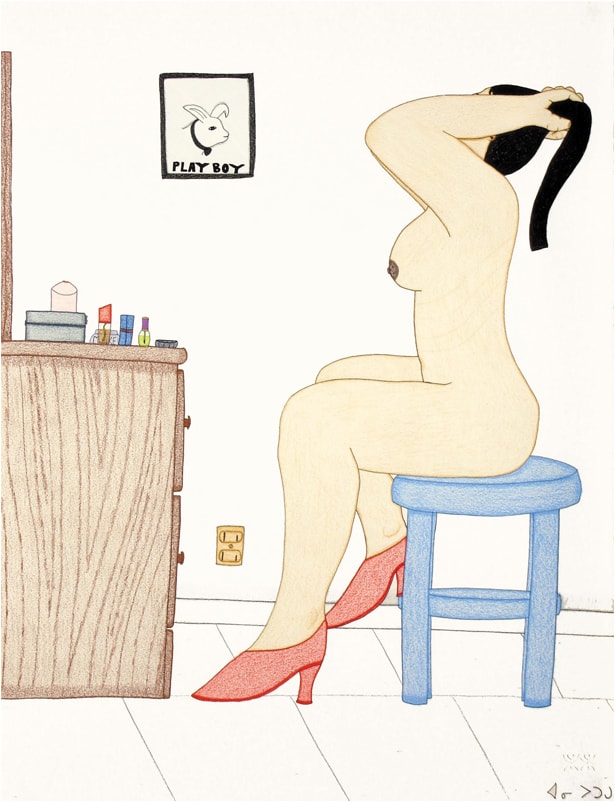

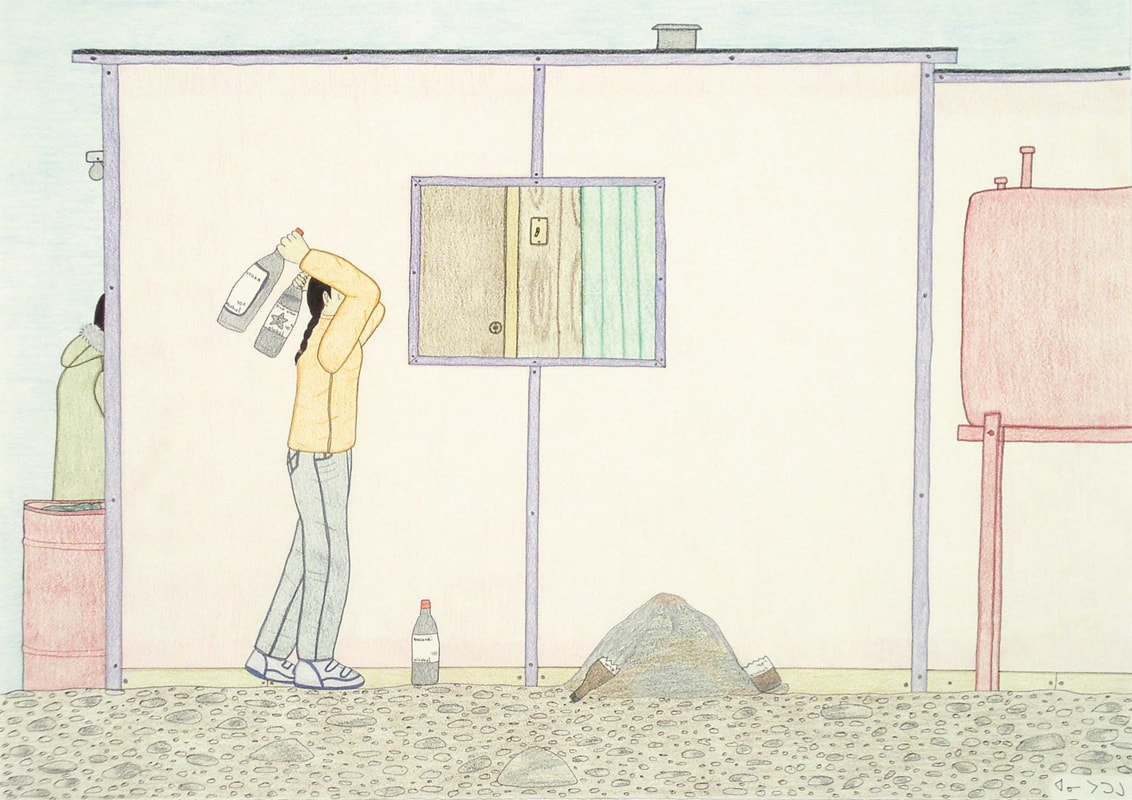

Unlike many of her peers, Pootoogook’s work challenges conventional assumptions made about “Inuit” art. Like her grandmother, Annie is a chronicler, and her drawings of domestic interiors and modern outpost camps reflect the disparate social, economic and physical realities of today’s Canadian North. Many of Pootoogook’s images are disturbing, addressing issues such alcoholism, domestic violence, suicide, depression and drug addiction. Many of these experiences are taken directly from her life and illustrated in her drawing. About one work, Memory of my Life: Breaking Bottles, 2001/02, she states, “. . . one time I drew when I broke bottles ’cause I got tired of drinking people every day. So I had to broke . . . break their bottles on the rock so they won’t drink tomorrow. I think I did a good job.” There are also highly disturbing drawings of Annie being abused by a former partner as well as numerous others of domestic violence that she has seen in her community. She reluctantly spoke of her own experience in an interview: “She [my sister] told me to get out of that house before he broke my bone. So my sister was in shock because I was going crazy. And I wasn’t normal anymore. But I had to charge him because what he did to me in that house, I had to charge him ’cause he used too much weapons on me and my life was lost.” Mental illness and anguish are also presented in a number of images that radiate yellow and red dots from the figures’ heads, symbolizing happiness and sadness. Again, Annie is reluctant to talk directly about these issues and prefers to let the work speak for her. She says, “It seems like I throw that shit out of mind and start drawing. Well, drawing makes me feel better . . . better a lot than before.” This selection of the psychological drawings is highly personal, highlighting her community’s ongoing struggles with mental health and addiction.

Television has been in the North for many years, and Annie is part of the first generation with consistent access to this medium. In her work we continually see familiar icons such as Jerry Springer, the Simpsons, Peter Mansbridge and Saddam Hussein. There is something unsettling about an Inuk viewing the contemporary world from an isolated location in the far north. Annie says, “I put war . . . wars [in my drawing] because I’ve seen it on TV, too. Like, Saddam Hussein, I was watching a long time ago when he was just wanting to fight people. So I decided to draw him and people on the background are dead. And many people all over the world know that Saddam is killing millions of people. So I decided to draw that because I didn’t like that Saddam Hussein.”

The most compelling images involving television are of Inuit watching traditional life practices such as seal or caribou hunting on stations like APTN. This representation highlights the mediation of broadcasting on Inuit life. “Like, if I visit and they’re watching Inuit on TV on traditional way, so sometime I talk to childrens that it’s better if you watch that . . . that way when you grow you’re going to learn how to hunt or cut animals. So they’re really excited and trying watch TV. And they say, ‘I wish I am going to be like that when I am growing.’ But I told them, you . . . you will if . . . if you want learn.”

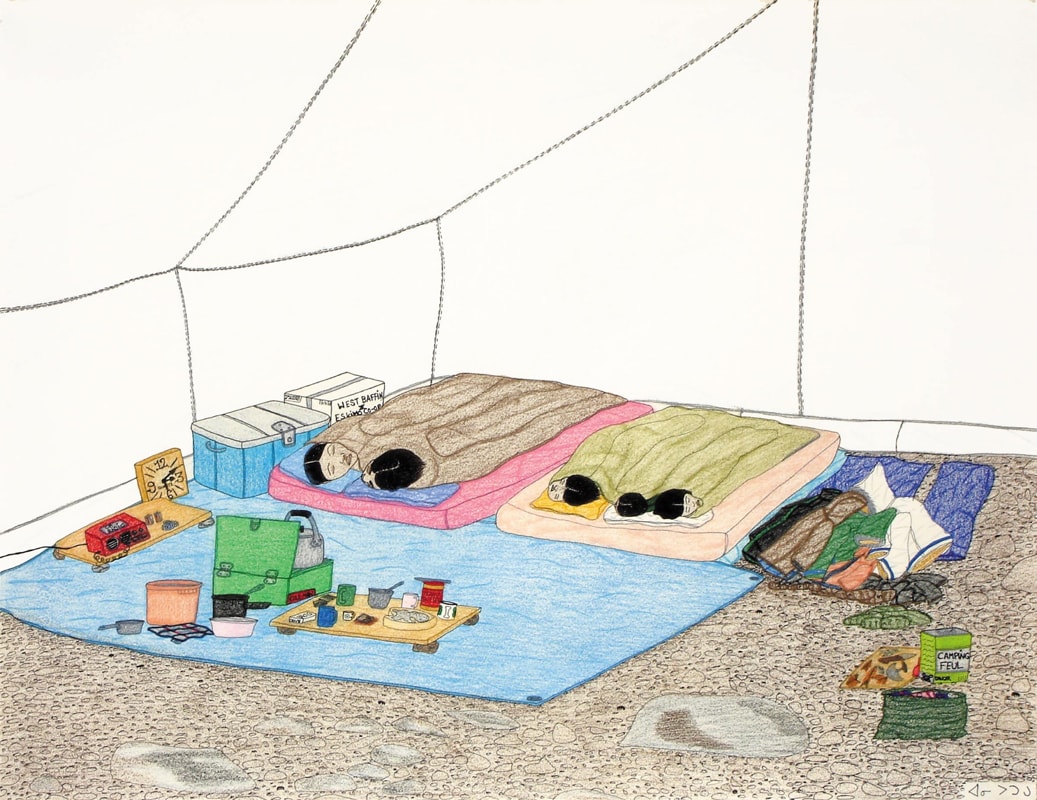

A large part of Pootoogook’s oeuvre and likely the most identifiable in terms of her practice are her domestic and camp interior drawings. These compositions are drawn from memory, compiling disparate images of objects and events from her everyday experiences in Cape Dorset. These works, like her mother’s and grandmother’s, are chronicles of daily life in contemporary Baffin Island. She takes a chair from one place, a stereo and people from another, and composes interiors that reflect life, depicting traditional Inuit activities such as seal tail parties, or the softening of seal skin, or eating on the floor, and seamlessly mixing them with Southern influences such as the furnishings, television and clothing. The walls of her interiors display decoration: calendars, clocks, keys and photographs that are typical in Inuit homes. Annie tells me that the reason a clock appears in every interior drawing is because everyone has a clock in his or her home. She expands on this with, “Cause we [Inuit] know . . . it’s the way of the world, time . . . that’s why I drew too. Cause all over the world knows the time. So I have to put the time too, all the time. Because we wouldn’t know if we didn’t have the time. So I put a time (clock) all the time because everybody knows.” Time in the Arctic is still negotiable. Our translator explained that a meeting scheduled for ten o’clock meant the artist would leave their house at ten, if at all. It remains a seasonal society that is only beginning to rely on standard time.

The camp interiors also display scenes from memory. There are the tools used in camp life on the land in the summer season; a Coleman stove, tents, knives, and fishing gear. The people drawn are often people from Annie’s past although she still values and treasures her time on the land today. These drawings are similar to her grandmother’s and mother’s drawings documenting life on the land, but with a contemporary twist. Annie states, “I never thought that this is traditional Inuit way, and this is white style. I never thought about that because I just draw what I see.” The reality shown in Pootoogook’s interiors is that Inuit life currently is a meshing of the traditional lifestyle with new ways adopted from the South. Therein lies the fascination of these compositions. This group of works teases the viewer into believing that Inuit life is still the idyllic life of the land but infuses it with contemporary signatures such as snowmobiles, radios and Ritz crackers.

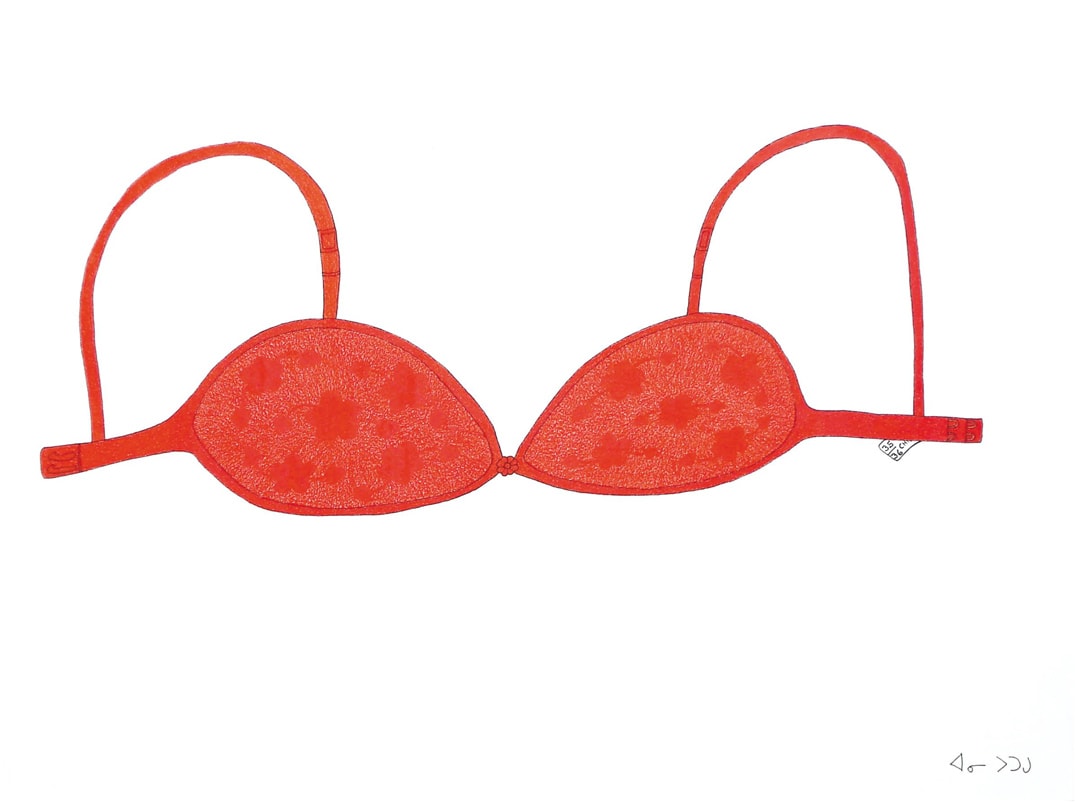

Pootoogook has recently expanded on the interior drawings by isolating objects of significance. Most notable are the black, heavy horn-rimmed glasses of Annie’s grandmother Pitseolak. Although Pitseolak does appear in many of Annie’s drawings and is identified by her heavy black glasses, the isolated glasses themselves, notated by a drawing pen and eraser, are a contemporary and emotional portrait of her grandmother (Glasses/Pencil/Eraser, 2006). Similarly, the Coleman Stove with Robin Hood flour and Tenderflake lard (ingredients for bannock) also combine to create a portrait of camp life that is telling and truly contemporary. The red brassiere in Bra, 2006 is also a telling portrait of modern sexuality, an uncommon theme in typical Inuit art. These objects in isolation do partake of the iconic presence associated with other items seen in many Inuit prints, like seals, fish, or loons; however, in the case of Annie Pootoogook the objects are from the South.

The work of Annie Pootoogook is notable on a number of levels. At thirty-seven, she is in the forefront of a generation of Inuit raised in two different worlds. Her work, like much recent art, explores the issue of Place, and expresses the flux of the global and the local. Because Pootoogook’s work is so idiosyncratic and highly personal, she has found a new language to communicate the Inuit experience. It reflects how dramatically the Canadian Arctic has changed in the past thirty years. Jimmy Manning, the manager of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, says, “Annie’s work is very different. Annie’s work is, like, today and yesterday and . . . daily happenings, shopping, music, the feast. Sometimes she will draw very hurting feelings from her heart which she’s not afraid to say on paper.”

Like many artists in Cape Dorset, she is a third-generation artist. Her grandmother, Pitseolak Ashoona, came from a hard life on the land. Her work depicted not only the life but also legends and transformation stories from her ancestors. Her mother Napachie did most of her graphic work in Cape Dorset and Annie grew up seeing these women make drawings on paper. Napachie also had something to tell in her work, and chronicled life in her time. Annie in many ways is carrying on this tradition of the narrative in her graphic work. Although some artists like Pudlo Pudlat have injected evidence of Southern culture, like planes and helicopters in to their work, Annie Pootoogook seems to be the first artist to expose and interpret the complexities of Inuit life today.

The exposure of Pootoogook’s work in the South in mainstream contemporary art venues, first through a solo exhibition at Toronto’s Power Plant Art Gallery and then through the Sobey Prize victory in Montreal, has sparked much debate about the work and the position Inuit art holds not only in the collections of Canada’s art museums but in the hearts of Canadians in general. On one hand Pootoogook’s drawings are not seen as serious or rigorous enough by some in the art establishment while on the other hand her art is deemed not “Inuit” enough by viewers who expect more traditional iconography. Yet the strength of Pootoogook’s work is that it simultaneously dispels the myth of the mystic north whilst documenting the changing way of life in Canada’s Arctic and reinforcing the necessity of its traditions.

Text is adapted from original essay, published by The Power Plant, 2006. Quotations taken from interviews with Annie Pootoogook by Katherine Knight and Marcia Connolly, Fall 2005, and Nancy Campbell, Spring 2006, in Cape Dorset.

Artist Links

- See, for example, Kristen K. Potter, “James Houston, Armchair Tourism, and the Marketing of Inuit Art,” Native American Art in the Twentieth Century, ed. W. Jackson Rushing III, (London: Routledge, 1999).[↑]

- Ingo Hessel, Inuit Art: An Introduction, (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre,1998), 11.[↑]

- For a history of the Arctic, see Alootook Ipellie, “The Colonization of the Artic,” Indigena Contemporary Native Perspectives, ed Gerald McMaster and Lee-Ann Martin, (Vancouver: Doughs and McIntyre, 1992), 39-58.[↑]