II. Back to the Future

Buried Fifties Station

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

Since the mid 20th century, when the U.S. first began to seriously squat the region, there have been three stations built at the South Pole. The first, constructed by the military, was a series of modest wooden structures not unlike those pictured in the 1951 film version of The Thing, where aliens and humans duke it out at the North Pole. 1 Never removed, these buildings are now almost entirely iced over, thus my image is an aerial photo of where the fifties station once stood (see Figure 5). Built at the start of the Cold War, the exposed vulnerability of these simple wooden modular units personifies the theme of that era’s Thing—”keep watching the skies” for an externalized “threat” to a fictionally coherent American “lower 48.” Additionally, if one watches early film footage of soldiers assembling these low-slung wooden kits (the walls often the same height as the troops), the unassuming design for the (then) future “space” colonization bears none of the markings of present day hyper consumer economy. Instead, it harks back to the simple mail order housing kits sold at the end of the 19th century by Montgomery Ward to growing westward populations settling areas newly cleansed of indigenous Americans.

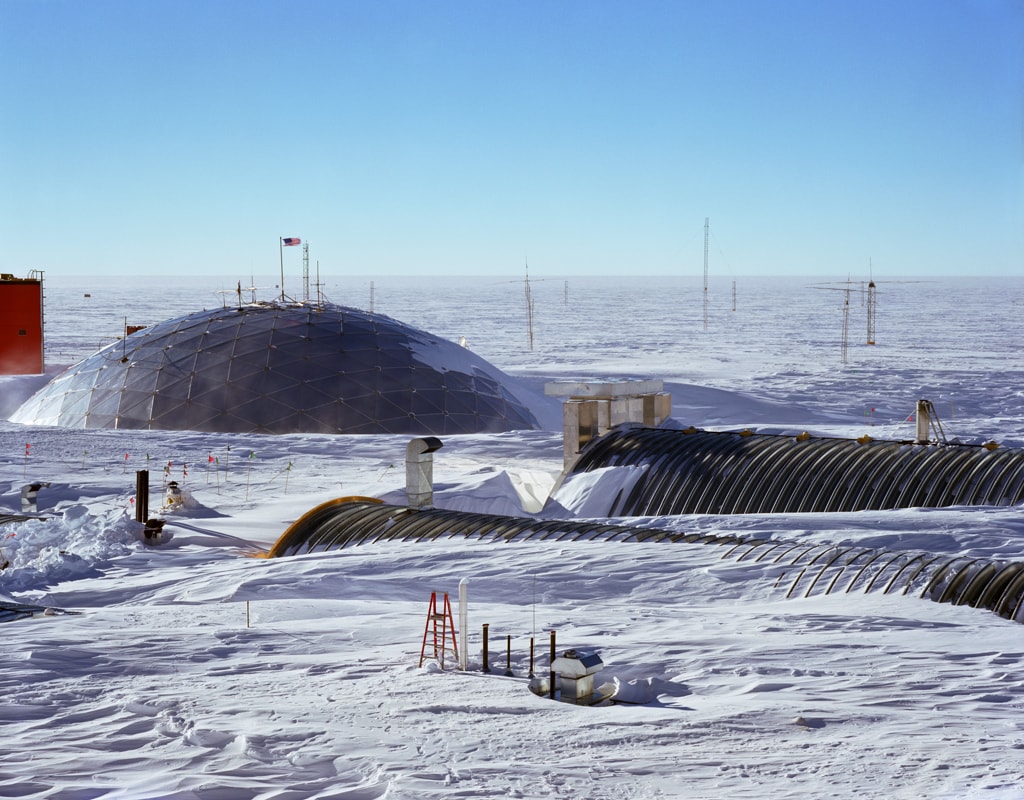

Dome and Tunnels

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

The next station, perhaps the most iconic one, is the Buckminster Fuller Dome built in the early 70s and now in the process of being “decommissioned.” Its interior set of red buildings have already been removed (see Figure 6). In a sense, this edifice embodies the legacies of contemporaneous social change movements, predominantly Fuller’s utopic (thus somewhat problematic) environmentalist vision for the collective stewardship of spaceship earth (“we are all astronauts”)—one that emphasizes individual responsibility, the power and primacy of design, humanist ideology, and technology as the force of ultimate liberation. 2 It’s interesting to consider that the Dome was designed and built during the height of political activism in the U.S., including the development of separatist movements among women, queers and people of color, as well a highly visible anti-war movement critical of U.S. imperialism and the then new war technologies like Napalm. The humanistic aspects of Fuller’s beliefs were, at the time, do doubt comforting to those invested in the ongoing project of American modernity, where the “good of mankind” and scientific rationality go hand in hand and where the foundation of these ideas, masculinity and whiteness, remain normalized. All this said, when compared to its box-like, relatively enormous replacement, there was an undeniable magic to being inside the Dome with its simultaneous layers of inside and out. Although the then “next” new and improved look of the future, the Buckminster Fuller design is almost as a modest as its predecessor both in its human scale and the simple durable design of interlocking triangles—a feature I employed in mirroring the image I took of the dome’s main living berths, focusing on the refrigerator-door escape hatches (fire exits) at the back of each compartment (see Figure 4). And despite the interior’s initially plain look, small individual design interventions abounded, especially in the sleeping quarters. It was telling that the upper echelon of the station’s management, having first choice between quarters in the new station or the Dome, all chose the latter as their home.

Underneath Amundsen-Scott Station

digital print

Courtesy of the artist

- The Thing, Dir. Christian Nyby. Perf. Kenneth Tobey, Margaret Sheridan, Robert Cornthwaite and Douglas Spencer. Winchester Pictures, 1951. In John Carpenter’s 1982 remake of The Thing, the characters have been “relocated” to Antarctica. Released at the start of the Reagan era, fittingly the script is reconfigured so that the greater “threat” now comes from within than externally from above.[↑]

- For a recent and varied discussion of Buckminster Fuller’s continuing legacy, see the series of articles published in Artforum, November, 2008.[↑]