The Performing Body and Fashion

Fashion was a useful instrument for constructing a public image; if a publicly known woman became associated with a particular type of dress, the dress became highly desirable and successful on the market. As Hermione, Thénard wore a robe à la circassienne (Circassian-style dress) in the fashion that had been popular decades before (figure 2). This misalignment did not make the choice of dress obsolete, but conveyed a greater sense of formality and gravitas. Thénard’s hairdo, similarly dated, complemented the robe à la circassienne (figure 3). The feathers and the pearls were meant to create a luxuriant and exotic effect. Romany’s rendering of the feathers makes them seem to take on a life of their own, in line with the tragic experience of the actress/character.

Costumes modify bodies. The painting as medium of representation alters the appearance of both costume and body, merging the two in a pictorial unit whose coherence is given by the theatrical subject matter and the vision of the painter. As Sarah Cohen defines in relation to the artist Antoine Watteau and the genre of the fête galante (elegant party in a parkland setting), the artful body was a privileged site of artistic practice that combined fashion and dance, and its patterns and motifs inspired architecture and the decorative arts. 1 In a theatrical performance like Thénard’s, the eighteenth-century tradition of the artful body fused with the bodily legibility sought by neoclassical taste.

Fashion was also a vital component of actors’ professional lives. It was equally important for portraitists, especially in the case of role portraits in which painter and sitter decided together on the historicity of the costume. In Romany’s portrait, Thénard’s costume evokes the status and perhaps even the psychological state of the ancient heroine, but sets the moment squarely at the end of the ancien régime in France.

A Network of Women Actors and Painters

In 1800, the staging of Racine’s Andromaque at the Comédie Française featured Thénard as Hermione and Francois-Joseph Talma (1763–1826) as Orestes. Talma’s intensely dramatic performance catapulted him to fame. He soon became the most celebrated actor of his time and an influential figure in a tightly knit social network that brought together women actors and painters. 2 At the level of material culture, Talma the actor represented a shared subject for visual artists of any gender, who depicted him in various media and techniques, including miniature paintings, prints, sculptural busts, and portrait medals. Although of different generations and associated with mainly divergent neoclassicist and romanticist styles, both Louis-Léopold Boilly (1761–1845) and Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) painted Talma in theatrical poses and costumes. A role portrait of Talma from 1818, long attributed to society portraitist François Gérard (1770–1837), has more recently been reattributed to none other than Romany. 3

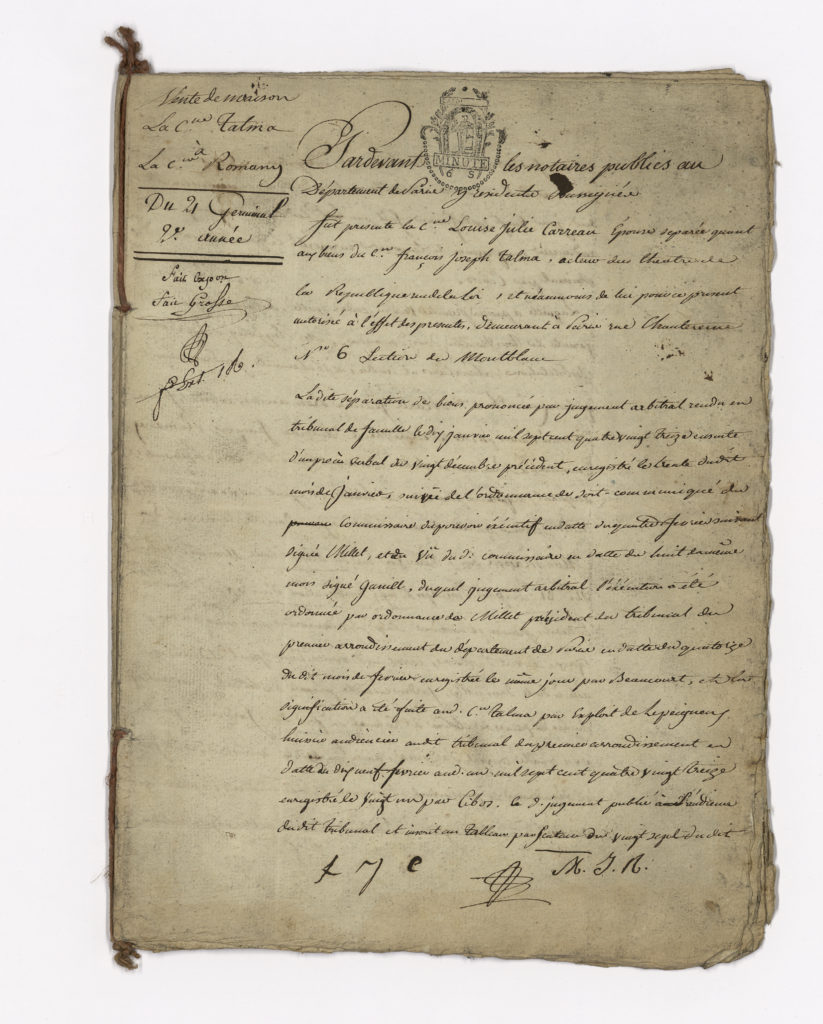

It might have been through Talma, a close friend of the highly influential artist and Jacobin leader Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), that Romany and Thénard connected and collaborated. Romany actively sought to forge strong ties with the world of theater. She even bought her house from Talma’s former wife (figure 4). Fully furnished, the townhouse was situated on today’s Chaussée d’Antin, a major street built in the eighteenth-century in an ever-expanding area of broad avenues known as les grands boulevards. As reported by travelers and journalists, including the British Henry Sutherland Edwards, the late-eighteenth-century Chaussée d’Antin quarters was a new and fashionable area of Paris that was gradually taken over by women actors, and especially by those who were equally known for being the mistresses of affluent men. 4 Mlle Guimard, Mlle Dervieux, Rosalie Duthé, Adeline Colombe, and Sophie Arnould all built lavish homes in that neighborhood, some of which were featured as tourist attractions in Parisian guides like the 1787 Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris (Guide for amateurs and foreign visitors to Paris). 5 By purchasing a house in the area and becoming a neighbor of these prominent actors, Romany chose to become an active participant in their social network, ruled by a combination of friendship and rivalry, competition and emulation, and, above all, a desire to be known publicly. Equally significant regarding Romany’s ties to theater is the fact that her second daughter, Lucie Cosnefroy de Saint-Ange, became an actor and a pensionnaire (junior member) of the Comédie Française. 6

Though she is utterly forgotten today, Romany was unusually successful in her lifetime. According to Carlo Jeannerat, as the recognized illegitimate daughter of the marquis de Romance, she was considerably wealthy. 7 The artist was married for several years to the miniaturist Romany, whose name she kept after their divorce. 8 She was a student of Regnault, and probably affiliated with the studio school for women led by Regnault’s wife. 9 A very prolific painter, Romany exhibited seventy-eight works at the Salons (official exhibitions of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), most of which were allegorical compositions and role portraits. 10 She received rare but positive reviews in the Salon pamphlets and, in 1808, was awarded the gold medal of the jury. 11

Despite her accomplishments, Romany was never as prominent as her contemporaries Elisabeth Vigée Lebrun (1755–1842), Marie Antoinette’s painter who left France for a long exile, and Adelaide Labille Guiard (1749–1803), the painter of the king’s aunts whose career was stalled by the Revolution. However, unlike Lebrun and Guiard, Romany survived the Terror professionally and was active in the post-Revolutionary art scene. In the early 1800s, Romany may not have had to compete with Lebrun or Guiard, but she did have to confront a new Salon system. While posing a different set of challenges, the post-Revolutionary art world allowed for a greater presence of women’s art. As Margaret Oppenheimer explains, the dissolution of the Academy in 1793 meant that a large number of non-Academicians, including a growing number of women, could now display works; three women exhibited at the Salon in 1789, while thirty-two women exhibited in 1801. 12 Romany’s ties to theater and her specialization in role portraits helped her to carve a name for herself among this competitive crowd of publicly known artists.

Romany, Lebrun, and Guiard shared many contacts among actors and playwrights. Without royal patronage, and especially after the Revolution, Romany relied on these connections to further her career. One such person was Amélie-Julie Candeille (1767–1834), who had a multilayered professional career as actor, playwright, composer, and critic, and who was a close friend of the painter Anne-Louis Girodet (1767–1824), David’s student. 13 As a critical thinker, Candeille helped shape Girodet’s identity through her writings on his art. 14 Candeille is also known to have collaborated with the playwright and political activist Olympe de Gouges (1748–1793) and with none other than Talma. 15 Candeille, Thénard, Romany, and Guiard all maintained personal and professional relationships with each other.

A portrait by Romany of Suzanne Vigée née Rivière offers another glimpse into this network of women actors and painters. Rivière enjoyed acting at an amateur level. 16 Rivière’s husband and Lebrun’s brother, Etienne Vigée was a playwright and a resilient cultural figure who passed smoothly through fast-changing political regimes, maintaining a strong connection with the Comédie Française – the theater that staged his plays and where both Candeille and Thénard acted. 17

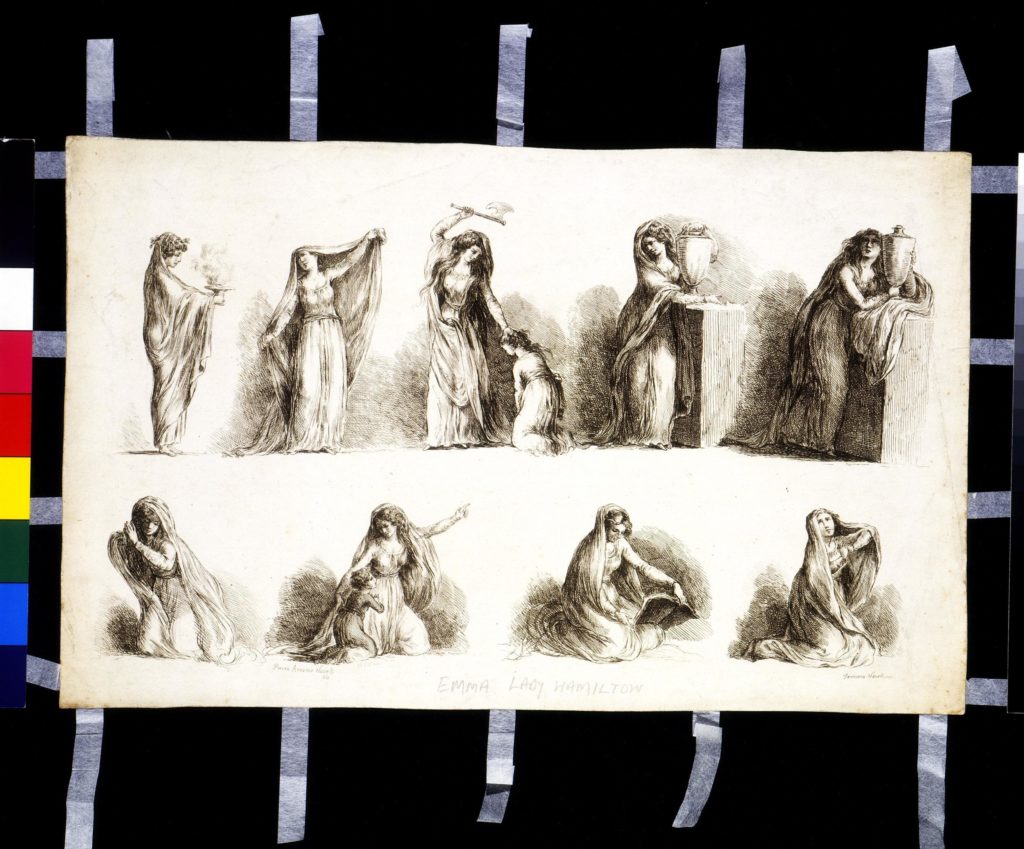

Another influential figure in this constellation was Emma Hamilton, the wife of Sir William Hamilton, the well-known antiquarian and collector, and the lover of Lord Horatio Nelson, the celebrated admiral who fought in the Napoleonic wars. Hamilton became famous for her attitudes, or impersonations that took the form of theatrical poses. Not a professional actor, but deeply involved in performance, Hamilton fascinated as an ideal model for portraits that encapsulate moments of acting. As seen in Francesco Novelli’s (1764–1836) etchings (figure 5), Hamilton combined shawl dances, inspired by Greek or Etruscan figures from her husband’s collection, with her attitudes, which required her to maintain body positions and facial expressions for a number of minutes. As a performer and a portrait sitter of international fame, Hamilton created bridges between the British and the French worlds of theater and the visual arts, especially for women in both fields.

- Sarah Cohen, “The Artful Body in Question,” in Art, Dance, and the Body in French Culture of the Ancien Regime (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).[↑]

- Herbert Collins, Talma, A Biography of an Actor (London: Faber and Faber, 1964); Bruno Villien, Talma: l’acteur favori de Napoléon Ier (Paris: Pygmalion/Watelet, 2001).[↑]

- Margaret Oppenheimer, “Adèle de Romance,” SIEFAR, 2004, http://siefar.org/dictionnaire/fr/Adèle_de_Romance.[↑]

- Henry Sutherland Edwards, Old and New Paris: Its History, its People and its Places (London: Cassell and Company Ltd., 1893). See also Norberg, “Actress/Courtesans,” 105–6.[↑]

- Norberg, “Actress/Courtesans,” 105–6. [↑]

- Carlo Jeannerat, “L’Auteur du portrait de Vestris II: Adèle de Romance et son mari, le miniaturiste François-Antoine Romany,” Bulletin de l’histoire de l’art français (1923): 52–63. [↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- The artist’s maiden name and married name have been used interchangeably and in combination: “Adèle de Romance,” “Adèle de Romance-Romany,” and “Adèle Romany” refer to the same person. [↑]

- Musée Magnin, Catalogue des peintres françaises (Dijon, 1938).[↑]

- Jeannerat, “L’Auteur du portrait.”[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Margaret Oppenheimer, The French Portrait: Revolution to Restoration (Northampton, MA: Smith College Museum of Art, 2005), 7.[↑]

- Joseph-Marie Quérard, La France littéraire, ou dictionnaire bibliographique des savants, historiens et gens de lettres de la France, ainsi que les littérateurs étrangers qui ont écrit en Français, plus particulièrement pendant les XVIIIe et XIXe siècles (Paris: Firmin Didot, 1827), 1: 180. See also Amélie-Julie Candeille, Notice biographique sur Anne-Louise Girodet et Amélie-Julie Candeille, pour mettre en tête de leur correspondance secrète (Paris : Bibliothèque Nationale de France).[↑]

- For more information on Candeille’s role as critic and historian in relation to her friend Girodet, see Heather Belnap Jensen, “Amélie-Julie Candeille’s Critical Enterprise and the Creation of ‘Girodet,'” in Women Art Critics in Nineteenth-Century France: Vanishing Acts, ed. Wendelin Guentner (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2013); “Quand la muse parle: Julie Candeille à propos de l’œuvre de l’art de Girodet,” in Plumes et pinceaux: Discours des femmes sur l’art en Europe (1750–1850), ed. Mechthild Fend, Melissa Hyde, and Anne Lafont (Dijon: Presses du réel, 2012). [↑]

- Jacqueline Letzter and Robert Adelson, Women Writing Opera: Creativity and Controversy in the Age of the French Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).[↑]

- Gita May, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun: The Odyssey of an Artist in an Age of Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 19.[↑]

- May, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 73. [↑]