|

Minoo Moallem,

"Passing, Politics and Religion"

(page 4 of 7)

Gozar, Taqlid, and Governmentality

The first time the audience is exposed to passing is when Reza enters

the prison's prayer room and learns from the other prisoners that he

does not need to be religious; he just needs to know how to pray

properly to appease the prison guards as a coping mechanism for being

disciplined. The film implicitly alludes to the centrality of appearance

and performance as modern sites of citizenship, gender identity,

inclusion, and exclusion. Indeed, taqiyyah, meaning concealment

or dissimulation of one's belief,[23]

has a long history in Islamic

minority/majority relations. In Iranian culture taqiyyah has

become an important strategic tool to justify religious, cultural, and

political performance. This idea has also been combined with another

concept, that of using a kola share or a jurisprudence hat, which

would justify transgression from the rule of law (Islamic Sharia)

through the reference to religious jurisprudence. Anyone can put this

hat on while trying to justify his/her unlawful acts of transgression

with the rule of law. These concepts have consistently created a

flexible and ambiguous situation where one can negotiate the rule of

law, or a space where the rule of law can be stretched and revised.

However, the distinction between the performer and the believer has made

Iranians more culturally aware of the gap between what is said and what

is done in practice. The testing of this gap has been crucial in the

Iranian political sphere and the politics of citizenship.

The plot develops when Reza Marmoulak steals the clergyman's garb and

turban and escapes the hospital by passing as an Imam, an akhund

or mullah. The body of the new character becomes a surface on

which the boundaries of masculinity and respectability can be both

regulated and transgressed. While Reza's beard, along with his garb and

turban, immediately gives him the appearance of an akhund, his

lack of knowledge of the rituals, especially in performing namaz-e

jama'at (prayer in the company of others as opposed to solitary

namaaz), puts his disguise in jeopardy. When a group of

travelling men ask Reza to perform a namaz-e jama'at at the

prayer house of the train station, Reza manages to conceal his lack of

knowledge by mimicking vudu (the preparation for the prayer,

including the ritual of washing the face, hands, and feet before prayer)

and by making up words that sounded like prayer.

The film goes beyond the dichotomy of tradition and modernity by

depicting religion not as the opposite of modernity and progress, but

well integrated within the modern nation-state. In addition to the

visual representation of trains, taxis, TVs, and telephones, a

conversation between Reza and his smuggler friend to arrange for a fake

passport to allow him to leave Iran reveals the influence of new media

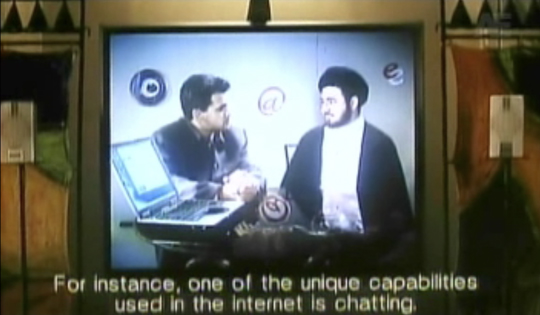

technologies and transnational film industry. In this scene, the

audience is exposed to a discussion on one of the public TV channels

between a religious figure and a show host on the capabilities of the

Internet. Reza repeats the words—Internet, chat, and multimedia—to mimic

words that he thinks are used by religious people. His friend advises

him to not listen to that particular akhund and try to instead

mimic the real clergymen who do not speak in those terms. In response,

Reza changes the channel and another clergyman appears, this time

discussing the movie Pulp Fiction.

Image 2 The film depicts the convergence of religion and new

media technologies by showing how the religious clergy men are informed

about and engaged with the new media including the Hollywood film

industry.

The film depicts religious spaces as integrated in the urban

landscape, as seen in the prayer house at the train station and the

mosque in the middle of a neighborhood. What divides the space are class

and gender relations. The religious space mediates different classes to

a limited extent. To reach out to the poor, the film offers two options:

either the mosque becomes more receptive to marginalized classes, or the

Imam should visit the poor in their homes. Reza takes up both by making

the mosque more receptive to a diverse group of people and using the

justification of visiting the poor at their homes to connect with the

smugglers.

Passing could be translated as gozar in Farsi, and McClintock

describes it as the "masking of ambiguity: difference as

identity."[24]

As Linda Schlossberg notes, passing is a highly charged site for

anxieties regarding visibility, invisibility, classification, and social

demarcation, and for the creation and establishment of an alternative

set of narratives or a novel way of creating new stories out of unstable

ones.[25] Passing also refers to the transgression of boundaries of

highly stigmatized identities[26]

and the strategic use of

identity.[27]

Passing should be understood in relation to similar

concepts such as mimicry (taqlid) and ambivalence

(doganegi). In his discussion of colonial mimicry, Homi Bhabha

refers to the discourse of mimicry as "the desire for a reformed,

recognizable Other, as a subject of a difference that is almost the

same, but not quite. Which is to say, the discourse of mimicry is

constructed around an ambivalence; in order to be effective, mimicry

must continuously produce its slippage, its excess, its

difference."[28]

In the case of Marmoulak, more than anything else, passing

provides space for the sexualized masculinity of the criminal and the

outlaw to not only be seen, but heard as well. I argue that passing,

mimicry, and ambivalence are not limited to the colonial context, but

also expose problems of normativity and criminality that are at the core

of modern disciplinary regimes of knowledge and power in the context of

both colonial and postcolonial formations. I employ the concept of

passing by broadening it and taking it into the context of political and

cultural citizenship. Passing and mimicry in this context continue to

create space for what Bhabha calls "at once resemblance and

menace"[29] given

the continuous reliance of postcolonial nation-states on

discourses of normativity and respectability, as well as gendered

subjects.

To perform respectability through masculinity, the film shows how a

religious act is achieved through the display of an ethical and

disciplined subject position who leads a virtuous life by resisting

temptation. Here, the pious masculinity of the clergyman converges with

the secular masculinity of the citizen as they are both subjected to the

rule of law and the disciplinary order of the nation-state (both secular

and religious). The abstract ethic of either a pious or secular

masculinity is transgressed by the hyper-masculinity of Reza, who

follows mundane pleasures along with a situated notion of what is just

or unjust through a perverse and forbidden exercise of power. For

example, when Reza takes the train to a border city, a mother and

daughter share a cabin with him. To his pleasure, once Reza settles into

the cabin the mother confides in him about her daughter's marriage

problems. However, as soon as the mother falls sleep, Reza starts

flirting with the daughter.

Here language leads to Reza's most challenging moment of mimicry when he struggles to transform

his flirtatious and sexualized thoughts into the language of sympathy

and compassion. The film shows how the mediation of proper language is

the pre-condition for entrance of the subject into the world of

normative masculinity. Also, his position as a respectable clergyman

becomes a limit to his desire to share the train cabin with the two

women; to Reza's great regret and in spite of his insistence on the

women staying, a fellow traveler moves the women to another cabin to

give Reza more space. It should be noted that while the film challenges

notions of criminality and respectability in both secular and religious

discourses through an interrogation of the pious masculinity of the

Islamic clergyman and the sexualized hyper-masculinity of the thief, it

does not question heteronormative citizenship. Instead, the film

reinforces heteronormativity by

constructing the sexualized masculinity of the thief as

heteroerotic.[30]

In the context of Iran, where there is a close link between the

embodied performance of identity, the politics of appearance, and dress

code in the formation of gendered notions of citizenship, an investment

in visual and visible modes of representation is crucial for issues of

governmentality. I refer to governmentality in its Foucauldian sense to

talk about technologies of domination of others and those of the self.

As I have argued elsewhere, the regulation of citizenship through visual

media has been critical for both the project of modernization and modern

nation-state building in Iran, as well as for the establishment of an

Islamic state. The performance of religiosity and secularism,

masculinity and femininity, and modern and traditional has been an

integral part of these forms of embodied

citizenship.[31] For example,

the instance of forced unveiling or veiling as a site of performance of

modern forms of gendered citizenship is a good illustration of this

situation.[32]

The concept of imitation or taqlid is not foreign

to Shia Islam because of the legitimacy of practicing taqlid to

follow a religious leader in legal and spiritual matters. The use of

garb and appearance in the film not only makes the body a surface for

mimicry and imitation, but also legitimizes the authority of the passing

subject to perform religious practices.

Passing is specifically significant in Iranian movies given the

importance of filmic space as an alternative site for cultural struggle,

and it has facilitated critical reflection on social issues. Information

technologies have become an important part of what Foucault calls "the

art of government," especially in regulating both discipline and

sovereignty.[33]

In other words, governmentality refers to the

connection between power as the regulation of others and as a

relationship with oneself, linking ethics and politics. Indeed, the

regulation of citizen-subjects through visual mediums has been central

to regimes of modern and postmodern governmentality and cultural

citizenship.

Through passing, Reza Marmoulak's character deconstructs rigid

dichotomies and binaries that have long influenced modern Iranian

political discourses. The film also transgresses the boundaries of

secular and religious, sacred and popular, modern and traditional, and

pious and criminal by juxtaposing and converging linguistic and

performative disciplinary practices. While passing does not deconstruct

subject positions or gendered and religious citizenship, it does provide

space for a critique of what stabilizes meaning and the body

historically, enabling the intervention of the investigating subject of

passing by unsettling modern notions of both respectability and

criminality.

Page: 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7

Next page

|