1. Introduction

This is the second of a pair of papers aimed at rethinking research into spatial cognition and sex/gender 1 as currently practiced in cognitive neuroscience. 2 Our group came together because of our shared dissatisfaction with the methods and the consequences of existing research, which calls for discussions about scientific practices as well as their social and political impact. To avoid a narrow fixation on specific elements of theories and practices of research into spatial cognition, we adopted the term “spatial stuff” to subsume the many constructs that are discussed as aspects of spatial cognition in the scientific literature, ranging from, for example, mental rotation to the navigation of the environment. Questionable claims of “robust sex differences” abound in neuroscience related to sex/gender and spatial stuff, and there appears to be an insatiable appetite for popular science report of such sex differences (Maney 2014). Unfortunately, media coverage does not typically address any potential methodological flaws of the original reports, and instead introduces misunderstandings and misrepresentations (Joel and Tarrasch 2014; Maney 2016). The consequences can be serious: studies suggest that exposure to brain-based findings and explanations, even if flawed, can reinforce existing essentialist beliefs and practices, for example the belief that gender inequalities in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields are explained by allegedly unequivocal neuroscientific evidence that “proves” that men’s brains are simply hardwired to excel in these areas (Brescoll and LaFrance 2004; O’Connor and Joffe 2014). In much the same way, however, the visibility of a broader variety of findings could challenge popular beliefs about gender differences.

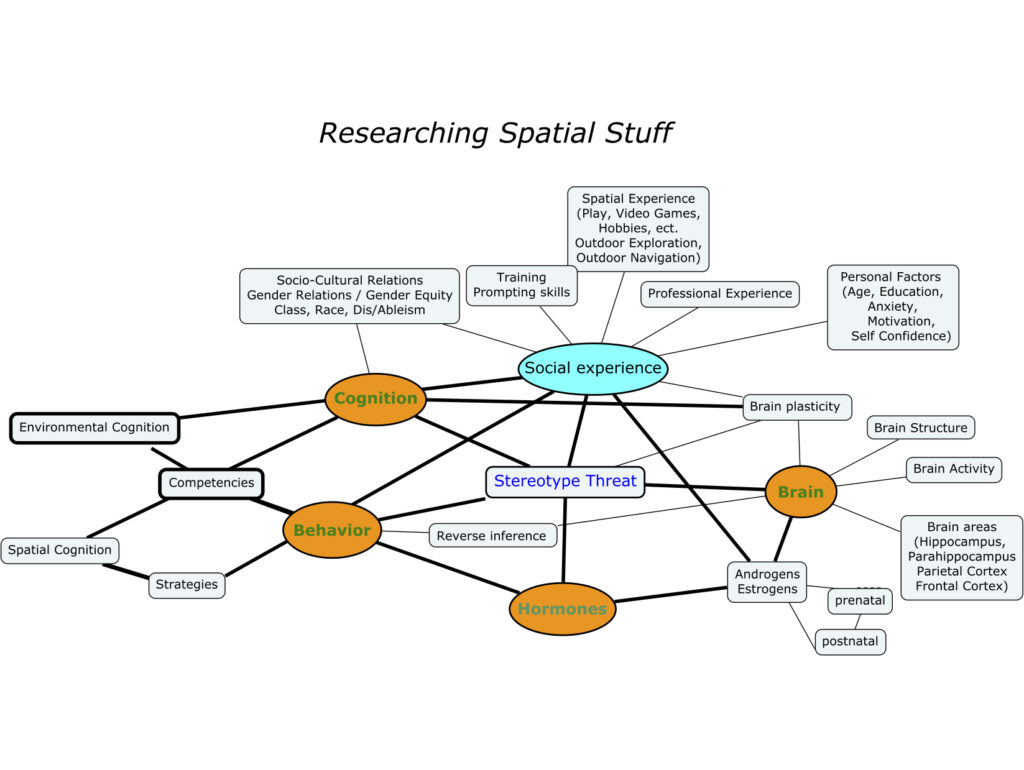

In the companion paper, we show that research on spatial stuff in the neurosciences has thus far primarily focused on comparing groups of females and males, on specific spatial abilities that predominantly relate to mental rotation, and on cross-sectional research designs. Because to date the preferred research tool in the neuroscience of spatial processing has been functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), we situated our discourse within this context. We argue that the focus on differences between binary sex/gender categories and on temporary snapshots of performance in highly specific tasks, such as those carried out using fMRI, represents an outdated perspective on sex/gender, spatial stuff, and brain development because it ignores evidence for human variability, neuroplasticity, and a wide range of related cognitions and behaviors. We identify a range of biosocial aspects/factors that can be associated with spatial stuff, many of which are ignored in the current essentialist approach to research in this area (see figure 1).

In our discussions as a group, we determined that a social context investigation of spatial stuff would require consideration of these multifaceted dimensions. Next, we debated how we might devise research protocols that would examine such aspects with less bias than current essentialist approaches.

In the present paper, we aim to make transparent parts of that debate to illustrate some of the difficulties and dilemmas that arise from multidisciplinary critical neuroscience perspectives that aim to acknowledge the gendered social context within which spatial cognition develops and operates. To identify the pre-existing assumptions and concerns we each bring to the debate, we initially declare our individual perspectives on the spatial stuff research arena. Second, we introduce these pre-existing perspectives as opening statements. Third, we discuss how to devise an experimental protocol suited for preregistration (we also present the rationale for this starting point). We highlight key empirical issues related to constructs discussed in the first paper, including participant selection, choice of spatial tasks (including both specialized performance in mental rotation and more general navigation strategies), and consideration of experimental design and analyses. In addition, we discuss how to measure the impact of sex/gender experiences (including stereotype threat and spatial anxiety) in light of brain plasticity and its implications for learning and trainability. Although our initial aim was to work towards a single protocol, as our discourse progressed it became clear that a single protocol would not allow us to address all the issues raised. Thus, we moved towards the collection of some preliminary considerations that can inform social-context based research into spatial cognition. We showcase (the beginning of) a negotiation process – an aspect of collaborative research that usually remains a nonpublic affair – and thereby make explicit several different feminist perspectives on designing a spatial stuff study, some of the different roads that can be taken in regard to the selection of variables, and the (dis)advantages of various options. The result is an advisory framework to inform social-context based research into spatial cognition. We conclude with the group members’ individual reflections on the process.

2. Pre-existing Perspectives on Spatial Stuff Research

Our different backgrounds inform our perspectives. The subjective and discipline-informed (e.g., biological, neuroscientific, philosophical, psychological) lenses we might use to examine a research problem and related explicit and implicit motivations might play into the way we approach research design, discuss constructs, and make decisions. To begin the conversation, we outline what we each bring to the thought space.

Vanessa Bentley

My interest in spatial stuff stems from my interest in the neuroimaging of sex/gender differences from a philosophy of science and feminist perspective.

When reviewing the neuroimaging studies on sex/gender differences on the mental rotation task, I have focused on studies’ theoretical framing and experimental design. What struck me was that almost all the studies assumed that men were naturally better at mental rotation than women and did not consider how social factors may affect the development of mental rotation ability. As such, most neuroimaging studies on sex/gender differences on the mental rotation task only tell part of the story. Thus, my first concern is that current knowledge on brain activation differences between women and men on the mental rotation task is limited by the narrow epistemological framework based on sex essentialism – the view that men and women are fundamentally different due to biological sex.

Second, there are also social and ethical concerns: some individuals and groups appeal to partial and distorted science, which supposedly shows scientific deficits, to explain the underrepresentation of women and minorities in STEM. Thus, partial and distorted science may be used to deny equal access to STEM opportunities, which results in further harms against women and underrepresented minorities.

My research aims to develop an alternate approach to cognitive neuroscience that addresses both epistemological and social/ethical goals: to create scientific practices that are better founded epistemologically, rather than being rooted in sexism and androcentrism, and to create scientific practices and knowledges that liberate oppressed, marginalized, or overlooked social groups.

To initiate inquiry from women’s perspectives is to make a more complete and less harmful story of spatial stuff possible. New directions may involve investigating how girls’ and boys’ different experiences growing up (e.g., being forced to choose gender-appropriate toys and play styles, being told that an activity is “for boys” or “for girls,” or that “boys/girls are good at X”) may affect brain development and translate to later performance differences.

Annelies Kleinherenbrink

My interest in spatial stuff relates to my interest in how neuroscientific theories and concepts affect understandings of ourselves and our society.

The brain takes on different (but often closely related) roles in popular neurodiscourses: it is often invoked as the cause and explanation of our conduct (the biologically determined brain, including the sexed brain), as the key to self-determination (the plastic brain, targeted by the “brain training industry”), or as the outcomes of our choices (again the plastic brain, now represented in terms of health risk or vulnerability).

Whereas sex/gender is routinely related to the biologically determined brain in both neuroscientific and popular literature, possible connections between sex/gender and neuroplasticity are often overlooked. Spatial cognition is a good example: it has been observed that men outperform women, on average, on measures of mental rotation. This difference is often represented as hardwired into “male brains” and “female brains” by evolutionary processes. This perceived fixedness and universality, in turn, is taken to imply that gender inequalities in STEM fields are inevitable and just. At the same time, a considerable body of research shows that spatial cognition is shaped by the environment in which we develop and by the situation in which measurements are taken – and that differences between women and men can sometimes disappear with practice. Yet studies that investigate whether context shapes sex/gender differences in spatial cognition by shaping the brain are scarce.

Tracing the emergence of brain differences in particular social environments would counter the pervasive biological determinism that characterizes sex/gender neuroscience. However, when developing this important and virtually unexplored terrain, it is important to avoid simply substituting biological determinism with social determinism. In our current neuroculture, the plastic brain often signifies a subject who is completely free to determine her fate – a subject who is in full control of her own body and whose choices and chances are unaffected by structural external factors (e.g., sexism, racism, poverty). This idea of the neoliberal subject introduces its own ethical concerns (e.g., it makes individuals fully responsible for their own health, happiness, and success). So, when we think about the plasticity of spatial stuff, questions that concern me include: Which opportunities to develop spatial competence are available to whom? Which individuals benefit the most from such opportunities, and why?

Feminist theory provides fruitful theoretical positions that resist an opposition between biological and social determinisms. In this current paper, we seek to develop research questions and methodologies that allow us to study spatial stuff from such a theoretical (and ethical) vantage point.

Gina Rippon

My interest in spatial stuff stems from my interest in the methodology associated with neuroimaging of individual differences and an awareness that, historically and perhaps inevitably, research findings in this area have been used to reinforce essentialist views and to sustain brain-based stereotypes.

My starting point with respect to researching spatial cognition is the role of the emerging acknowledgement of the life-long plasticity of the human brain, at the same time that much contemporary sex/gender neuroscience research fails to acknowledge the implications of plasticity both in research design and in interpretation of sex/gender differences when they are found. We have increasing knowledge of the brain-changing effects of a gendered world, that is, a world where experiences, opportunities, expectations, attitudes, etc., will be different for those of different genders. This very entanglement is characterized by studies of stereotype threat, by which a self-belief in a socially constructed label of inferiority will negatively affect performance and serve as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Commonly identified as the one sex difference that has robustly stood the test of time, spatial cognition is a powerful male/female differentiator in the public domain and in the cognitive neuroscience research forum. Examining the evidence for spatial cognition as a stable, sex-differentiated skill is important. It is not only thought to be central to capabilities for STEM (where women remain underrepresented), but to possibly have implications for status and power due to the role of academic success in social and political hierarchies.

Diana Schellenberg

My interest in spatial stuff derives indirectly from my interests in research methodology, in the role of science in the manifestation of social power dynamics, and in how social categories like sex/gender 3 are constructed 4 in research.

My perspectives in the present context are mostly informed by a background in assessment, experimental design, measurement in psychology, learning theories, and social constructionism. They are also informed by my research on the perspectives of scientists and of potential study participants who identify with LGBTQI* 5 contexts on sex/gender assessment. I do not think that there is necessarily one right way to conduct research, nor do I think it can be free from all bias. However, some ways can be more useful than others and, from both ethical and methodological perspectives, some practices or motivations can certainly be highly problematic or even wrong.

To me, spatial stuff is an interesting example for sex/gender-related constructions because its subconstruct mental rotation has been upheld as one of few psychological constructs that show differences between groups of “women” and “men.” However, even from a methodologically conservative standpoint, findings that involve such labels are often questionable because, although the categories may seem obvious, they can fail to meet scientific standards and may not provide much useful information, especially when information about the underlying definition, operationalization, and rationale is missing (for more details, see Schellenberg and Kaiser 2018; Schellenberg 2018). Therefore, and because they disregard the range of human experience (including, e.g., marginalized identities or bodies; intersections and interdependencies of multiple social categories, and related experiences of privilege and discrimination), I am sceptical of the generalized use of labels such as “women,” “men,” “males,” or “females” in research. I would argue that sex/gender is more ideally accounted for when it is viewed as (a) changeable set(s) of multivariate, multidimensional, situated, context-dependent, fluid, and often interrelated constructs, which may not involve obvious sex/gender terminology (in which case initial sex/gendered attributions may become obsolete).

To overcome the use of mutually exclusive and possibly invalid sex/gender categories, I think it can be useful to clarify what sex/gender is in the context of our prospective study, which assumptions about other attributes or constructs it may entail, and how those assumptions relate to spatial stuff. I assume that the social constructions of sex/gender and of spatial stuff are quite entangled. Thus, potential sex/gender variables could include an open answer to current gender identity, but they could also turn out to be something like the number of times someone has used a map (for one of its designated spatial purposes). This does not mean that I think that any stereotyped construct is automatically a plausible operationalization of sex/gender, or an indicator of some true sex/gender, or vice-versa. On the contrary, (subjective?) experience-with-maps variables may be entangled with (but do not need) sex/gender; in addition, their expression likely varies considerably between individuals (and maybe even within individuals), and they have more to do with spatial stuff than do undefined labels. Thus, temporarily identifying spatial-stuff-related constructs as potential sex/gender variables (and vice-versa) could be one way to deconstruct assumptions that are otherwise concealed by labels that may not provide relevant information for a study.

Sigrid Schmitz

My interest in spatial stuff is to change the focus to the developmental aspects of bio-social entanglements which can result in a change from a priori to a posteriori categorizations of group characteristics apart from sex/gender.

Neurofeminist research for years highlighted plasticity concepts – which have already been researched for more than forty years within the neurosciences – to outline nature/culture intersections and bio-social entanglements. The plasticity perspective was indeed fruitful to disrupt concepts of reductionist biological determinisms of seemingly natural brain causes that are used to legitimize gendered (and intersectional) societal orders and norms. Plasticity arguments have led to a reconsideration of the bio-social brain on material, behavioral, and identity levels, as well as on epistemological levels. The plasticity perspective can serve to focus on developmental processes in spatial stuff that lead to entangled and contingent outcomes.

One approach for a first consideration would be to analyze strategies in spatial stuff, instead of skills. Gendered experiences act upon the development of strategies as well as of competencies. Gendered experiences frame individual preferences for spatial and environmental strategies, e.g., favoring landmarks to directions in orientation. Strategies are implemented in one’s own behavioral repertoire, influence the manifestation of mental maps, and, in consequence, spatial and environmental competencies differ as a result of to these experiences (Schmitz 1999).

Due to sociocultural influences and individual experiences with spatial strategies and competencies, approaches that explore differences in spatial stuff for just one or two simplified a priori categories (e.g., participants’ sexes) are incomplete. Although there is a need for categorization, the development of pattern or cluster of spatial stuff groups a posteriori (i.e., from the data) would be a more adequate data analysis method. This means that investigators should not categorize participants a priori and then assess potential differences between conditions and groups (e.g., through ANOVA). Instead, they should use cluster analyses to resolve patterns of connected categories that relate to strategies or performances in spatial tasks (Norman et al. 2006; O’Toole et al. 2007). A posteriori clustered patterns of categories might include gender, race, class, age, gender identification, gender role identification or rejection and to what degree, education level, and profession; they might also include experience-dependent variables, such as stereotype threat variables, anxiety/motivation variables, and strategic variables.

Summary

As a group we share the concern that research in spatial stuff to date is characterized by failures to acknowledge sociocultural factors and individual experiences and that ignoring the evident plasticity and malleability of brain-based correlates and experience-based performance necessarily invalidates much research in this area. With respect to methodology, we note that the classic mental rotation task is frequently and unquestioningly selected as a proxy for all forms of spatial skill, focusing mainly on performance rather than on strategies. The “prelabeling” or categorization of participants in advance of any kind of empirical study was raised as a concern. Rather than widely used but poorly defined and inadequate, binary sex/gender labels, we agreed that pre-experimental labeling should focus on variables that are immediately relevant to spatial stuff.

We share a concern that the outcomes of restricted essentialist-based research are frequently used to justify phenomena related to discrimination, as well as concerns about replacing biological determinism with social determinism. In addition, our statements show that spatial stuff is a research arena where the potential political impact of findings needs to be acknowledged.

3. Conversations around Writing a Sex/Gender-Informed Research Protocol(s) for Improved Spatial Stuff Research

Here, we present our conversation about issues that may be relevant for research that aims to incorporate social context in spatial stuff. We first present the rationale for situating parts of our discourse in the context of devising preregistration protocols and some cautionary assumptions (3.1). We then turn to the question of what our ideal research protocol would be, which, in our discourse, quickly revealed difficulties associated with the complexity of a multifaceted approach, as well as areas of dissensus associated with how to specify, select, and operationalize variables. In our discussions, we therefore explored various scenarios and simultaneously discussed ideas for several hypothetical studies that could be part of a larger project. We present our explorations with selected and partially revised excerpts 6 from our exchanges to illustrate some of the different roads that can be taken in developing a variety of feminist research protocols. After we elaborate on issues related to participant selection and sex/gender (3.2), we explore how to account for experiences and plasticity (3.3). We then consider the selection of spatial tasks (3.4) and hormones (3.5), followed by some additional considerations about design and analyses (3.6). We offer the resulting considerations as guidance and inspiration for research teams working in this area, as they present a range of issues that we feel should be considered or made explicit (along with the rationales for the decisions that are ultimately made) before a study is conducted and published.

3.1 Initial Assumptions about Preregistration Protocols

Our discourse about integrating a social context approach in the research of spatial stuff was entangled with the question of how researchers devise specific experimental protocols. To deconstruct this process, we initially decided to partially frame our discourse around the emerging practice of preregistering protocols prior to publication. This focus was additionally motivated by the idea that some aspects of preregistration have the potential to improve research practices related to spatial stuff in ways that can be consistent with many feminist researchers’ perspectives (Rippon et al. 2014).

The preregistration of protocols, or “registered reports,” is a practice whereby full details of a proposed study are submitted and peer-reviewed in advance of the study being carried out. These details include key research question(s), hypotheses, participant selection procedures (including exclusion and inclusion criteria), the proposed methodology (e.g., tasks, conditions, control groups), and proposed analyses, together with a statistical power analysis. Corrections/adjustments to the protocols can be made on the basis of reviewer feedback. Once accepted (via in principle acceptance, or IPA), the study undergoes traditional submission and review procedures before its publication, pending the use of “the exact methods and analytical procedures outlined, as well as a defensible and evidence-bound interpretation of the results” (Chambers 2013; Chambers, Feredoes, Muthukumaraswamy, and Etchells 2014). The outcomes of all registered analyses must be reported, whether or not any statistically significant findings emerged. Researchers can add additional analyses once the data have been collected, but these must be clearly identified as exploratory analyses and any post-hoc inferences based on these should be identified as such.

The preregistration of protocols is currently more common in the clinical sciences, but the strategy is becoming popular in behavioral sciences in the light of recent concerns about the lack of replicability in behavioral science (OSC 2015; Munafo et al. 2017), questionable scientific practices such as HARKing (hypothesizing after the results are known, Kerr 1998), p-hacking (data dredging, data mining, repeated testing of data sets without a priori hypotheses), and what has been described as the troubling trio (underpowered-studies, reporting of “unexpected” results, and consistently weak p values; Lindsay 2015). These problematic research practices are particularly pronounced in sex/gender research (see, e.g., David et al. 2018); the use of preregistered protocols could help resolve some of the problematic methodological issues (Rippon et al. 2014; Rippon et al. 2017), including those that we identified for the context of spatial stuff research.

Some of the proposed goals of preregistration that resonated with our group’s critique of spatial stuff research pertain to calls for enhancing the quality of research practices by improving methodological transparency on evidence-bound interpretations. For example, the complete reporting of the outcomes of all proposed data analyses may help address the problem of publication bias where the majority of studies only report the sex/gender differences that are found, but not the instances in which they are not. Relatedly, an insistence on evidence-based interpretations promises to reduce the continuation of research based on unjustified explanations. For example, as observed elsewhere (Rippon 2016; Bluhm 2013a, 2013b), it is common for neuroimaging findings to be interpreted in terms of behavioral stereotypes based on measures that were not even obtained during scanning. A reduction of such HARKing practices has the potential not only to address immediate methodological flaws but also to prevent misguided applications of research findings.

Preregistration obviously will not solve everything. One example of a technical issue that could remain is the matter of how investigators report differences. Reporting average group differences is less informative than reporting effect sizes, which indicate whether statistically significant mean differences actually clearly distinguish between two groups (Cohen 1988). This is a key issue in sex/gender research, where the degree of overlap between groups may not be made evident, informing ill-founded conclusions about male/female differences (Ingahalikar 2014; Joel and Tarrasch 2014).

There are also deeper, philosophical problems that preregistration cannot address. For example, although preregistration practices can improve the standards of the scientific communication of findings and increase the visibility of perceived sex/gender similarities, one feminist epistemological concern is that these practices do not critically examine or expose the sexist, sex-essentialist framework that backgrounds much research on sex/gender differences. Sex-essentialist research protocols can be submitted for preregistration and researchers with sex-essentialist perspectives can continue to publish their work without seriously engaging with the possibility that what is interpreted as sex/gender differences may be associated with social influences or the interaction of social and biological influences, rather than with sex or sole biological influences. An alternative or necessary addition to preregistration thus involves a critical examination of the sex-essentialist assumption. An informed approach to research protocols, which pays explicit attention to feminist epistemological concerns and to study-specific entanglements (including the participant selection, the analytical pipeline, and the research findings’ interpretation) could foster the establishment of clearer criteria for reliable research. Where proposed research appears to be working within a strictly essentialist framework, reviewers could call for clarifications and specify the inclusion of additional psycho-social perspectives.

Despite some potential caveats, preregistration protocols may provide a backdrop for making transparent the negotiation process around concepts and variables that are used in spatial stuff research. It can offer an opportunity to discuss how and why decisions were made, how they have been justified, and what was included or excluded. These desirable aspects fit with our group’s critique of current research on spatial stuff and our aims to not only challenge sex difference findings but to also reflect on research design, including the definition of terms, the selection of variables and accounting for the complexity, interactions, and entanglements of social positions, experiences, spatial constructs, neuroscientific correlates, and sociopolitical context. Below, we present key elements of our negotiation of general issues that must be resolved for conducting nonessentialist research on spatial stuff and sex/gender. While we initially aimed for a specific protocol, we decided that the negotiation itself was worth documenting, and we present it here as an advisory framework relevant to a variety of preregistration protocols.

3.2. Working with Entangled Variables: Sample Selection and Sex/Gender

We start our documentation of the negotiation process with the discussion of how – if at all – participants in spatial stuff research could be categorized. Recurring themes in our conversation include the entangled character of considerations that pertain to participants as individuals and related “person variables,” the general constructs being studied, and the concrete methodological aspects of the research design.

3.2.1. Sample Selection

One area of consensus in our group was that, as researchers, we would aim to be as inclusive as possible and seek a diverse sample of participants. The implementation of this goal can take various forms.

Diana: Like all other aspects of our hypothetical study, the questions of who the participants of our experiment could be and which additional, potentially relevant variables (e.g., predictors and covariates) they could bring into the mix are deeply entangled with the design and the entire study apparatus. As such, they are potentially relevant for ethical as well as methodological (reliability, validity, and generalizability) issues. In the present context, we may want not only to discuss spatial-stuff related, overt sources of stereotype threat but also to evaluate which limitations our instruments and setting could impose on the sample (and vice-versa). For example, a procedure that evokes a medical setting (e.g., in an fMRI study) or tasks that resemble abstract aptitude tests (e.g., the presentation of stimuli in mental rotation tasks) may pose a potential stressor and automatically exclude participants who have experienced discrimination and pathologization in medical or educational settings. This can disproportionately affect persons who are already negatively affected by essentialist policies and who have experienced stigmatization or discrimination related to, for example, ability, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, or other markers.

3.2.2. Sex/Gender

It has been common practice in the neurosciences to assume that biological sex is a simple binary category that can be treated as an independent variable, with participants allocated to one of two groups – male or female. However, it is becoming clear that molecular, neural, and behavioral data do not fit this characterization (Ainsworth 2015; Fausto-Sterling 2000b; Joel et al. 2015; Reis and Carothers 2014; Richardson 2013). Furthermore, there are clear indications that many other physical variables (such as body weight or head size, in the context of neuroimaging studies) and social variables (such as years in education, occupation, socioeconomic status), which may covary or interact with conventional sex/gender variables, must be taken into account in exploring so-called sex influences (Fausto-Sterling 2000b; Rippon et al. 2014, 2017). In a related vein, researchers have proposed that the meaning, relevance, reliability, operationalizability, plausibility, and validity of sex/gender variables may depend on various aspects that relate to a study’s context (Schellenberg and Kaiser 2018; Schellenberg 2018). Thus, sex/gender questions were of crucial importance for our discussion, and our conversations revealed some major points of concern. They involved questions about whether or not to include sex/gender as an explicit variable in our hypothetical study and, if so, how it could be operationalized and which role it would play.

Diana: Which aspects of sex/gender are important to you in this study? Which purpose would they serve? Although I would personally prefer a more concrete, context-driven operationalization of sex/gender stuff, such as spatial-stuff-related socialization experiences, I am open to including self-assigned or externally assigned labels. However, I would need to understand why we use them and how we want to operationalize them. For example, if we use group labels such as “female” and “male,” how will we determine who belongs to which group? And how, specifically, are those groups linked to spatial stuff outcomes?

The conversation developed into a discussion about opportunities of neurofeminist-informed studies to extend or revise traditional neuroscience approaches to studying sex/gender or to radically transform how the neurosciences think about sex/gender.

Vanessa: Should we move away from sex/gender categories or include them in our study? I see two alternatives. The first involves investigating how sex and gender interact (such as the possibility that girls/women and boys/men experience different spatial experiences and gendered messaging about who is competent at spatial tasks throughout their lives) to explore whether (1) social experience and experimental context better explain performance on mental rotation performance than sex, or whether (2) social experience and experimental context interact with sex/gender, and that better explains mental rotation performance than sex alone. I see this project as a bridge project to demonstrate the failings with the traditional sex lens and open up new approaches to the traditional question of sex differences in mental rotation.

The second alternative is to skip this bridging and just imagine an ideal experiment in which we completely break free of the traditional sex approach. Whereas the bridging project will show the empirical inadequacies of the traditional approach and identify more productive avenues, such as recognizing that what is being studied is sex/gender, this more radical open gender (and possibly no gender) approach liberates us from the strictures of current dichotomous sex/gender thinking. Although I think this is ideally our goal, I do not think science and society are ready for this yet. My concern is that such an approach, though quite freeing, has no connection to sex-differences-as-usual research and cannot be used to debunk the standard approach. On the other hand, the no gender approach has the potential to be a radical change in thinking about spatial stuff and may instigate a whole new line of research.

So here are our two choices; is it possible to pursue them both? Collect all the variables and analyze both ways? Or is continuing to think in terms of sex/gender going to perpetuate binary thinking?

Diana: I am open to both options Vanessa suggests, especially because clarifying our research questions and focusing on something specific such as the proposed examples about mental rotation performance would make it much easier to discuss design-related issues and the operationalization of sex/gender.

Gina: We should remember the aim of this project is to improve practices in investigating spatial stuff. This, for me, would include going beyond/replacing the normal practice of a simplistic comparison of males and females, with little or no account taken of any other demographic information (such as occupation, education, spatial experience, spatial anxiety, etc., as per our recent discussions). But we would need to illustrate why this would be necessary by incorporating a comparison between the old-fashioned way to analyze a data set and the output from an analysis that took many more pertinent variables into consideration.

Annelies: I am also drawn to a design that functions as a bridge between the business as usual of studying sex/gender and spatial stuff one the one hand, and a research program that completely avoids reproducing the binary male-female on the other. As the literature summarized in our review in the first paper suggests, some factors that are the building blocks from which sex/gender categories are constructed (e.g., play activities, stereotypes, hormones, etc.) are the same factors that might contribute to the development of (individual or group-based differences in) spatial cognition. Would it then be right to state that the connection between sex/gender and spatial cognition is a spurious one – not one of cause and effect, but two effects of other, shared causes? That would be a good reason to relinquish sex/gender altogether when studying the development of spatial stuff.

Personally, this is where I would like us to arrive eventually, but I do think some intermediate steps could be useful and important – that is, correlating sex/gender and spatial performance as it is typically done (i.e., treat male-female like two boxes, the meanings of which are more or less taken for granted, using self-report), and then showing that paying attention to a selection of (social, psychological, physiological) factors (e.g., past play activities, stereotyping, hormones, etc.) does a better job of predicting individual differences in spatial cognition than sex/gender. With these steps, we gradually move away from sex/gender. As we do so, predictive power (i.e., our understanding of spatial stuff) should increase. I see a parallel here with the recent discussions about gendered healthcare, where Springer, Stellman, and Jordan-Young (2012) remark that “sex is not a mechanism,” but almost always a proxy for stuff we are actually interested in. If we focus on actual mechanisms and processes, sex disappears as we get a host of new (better?) explanatory variables – but in a way we can also still keep talking about sex/gender to the extent that these alternative variables co-vary with it and are part of it.

Diana: First, to clarify, my remark on the design for a bridge study was merely methodological: To me, the question “what does a better job at predicting” is slightly different from – and requires a different study design than – the question “how much of the variation (in a given spatial stuff outcome variable) is likely be explained by…?” I think the idea of a bridge project is great. It is only the proposed inferences with which I would be careful.

Second, Annelies’s summary very much relates to the point I have been trying to make: most categorical operationalizations of sex/gender are likely placeholders for something else. In a related vein, I do not necessarily view sex/gender as one distinct variable but rather as ever-changing and entangled constructs with a bunch of potential subconstructs, which, depending on context, may or may not turn out to be useful variables for a study. Similar to the building blocks to which Annelies referred, these could be things that are socially readily associated with gender/sex (e.g., self-reported gender identity; birth-assigned sex), but they could also be things whose entanglement with social constructions of sex/gender is not necessarily implied by name or definition but which may be of more immediate relevance to a research topic.

Finally, although I think it is ideal to replace sex/gender categories with variables that more closely relate to the actual research topic, this does not mean that it is my aim to relinquish sex/gender altogether in our study of spatial stuff or that I am automatically opposed to using whatever sort of sex/gender variables people find useful in a study. I simply find it appropriate to apply the same logic to variables that pertain to social categories that is expected for any other variables in a research project. This, to me, involves a clarification of the purpose and meaning of the variables and their values, how we assess them, and how they relate to our research question.

Gina: I had assumed that we would collect all agreed variables (including M/F) and then find ways to analyze them all. With an appropriate multivariate regression, we should be able to demonstrate how much of the variance is accounted for by these variables. The key issue with regard to biological sex is that it is so entangled with gender-based variables (as per the diagram in Rippon et al. 2014) that it then becomes problematic to interpret any statistically significant differences that might emerge. But if we have the additional data on, e.g., video game experience, spatial anxiety, occupation, etc., we might be able to open the debate on what other factors influence spatial stuff.

Sigrid: I think we should prioritize other social categories or variables over sex/gender categories. For me that would mean leaving sex/gender variables aside for the first analysis of data and instead trying to extract other relevant (social) categories that could explain task performance and strategies. I think a possibility could be a cluster analysis of groups of variables (not subjects) that are related in explaining strategies or performances.

Given the role that existing sex/gender constructs play in the oppression of, for example, individuals whose birth-assigned sex does not align with their gender identity and/or women, we sought alternatives to an uncritical use of sex/gender categories, post-hoc sex essentialism, and stereotypes to explain differences in spatial cognition and behavior. Strategies may include approaches that explore data to reveal new categories, influences, and connections. The idea of data-driven rather than stereotype-driven interpretations illustrates that explorative analyses, which have often served to produce bias, can also serve to reduce it 7

3.3. Accounting for Experiences: From Stereotype Threat, Anxiety, and Confidence to Learning and Trainability of Spatial Stuff

Our literature review in the first paper revealed a complex network of interacting biosocial variables that could affect or correlate with spatial stuff. This included stereotype threat, spatial anxiety, and confidence as well as participants’ previous experiences with spatial stuff and experience-dependent plasticity, a commonly overlooked phenomenon in neuroscientific sex/gender research into spatial stuff (Fine et al. 2013).

3.3.1. Accounting for Stereotype Threat, Spatial Anxiety, and Confidence

Our group agreed that stereotype threat is an important generic factor in spatial stuff research.

Gina: Stereotype threat is one of the factors that has been considered as significant in sex/gender differences in spatial stuff, although a recent meta-analysis suggested that the effect was not as powerful as the effect on maths (Doyle and Voyer 2016). But studies on mental rotation by MaryJane Wraga et al. (2007) showed that the way a task is presented (in a positive light versus in a stereotypically negative way) matters in terms of both brain activation and error rates for women. So stereotype threat is certainly a factor that should be considered, even if it is only controlled for by, say, asking questions about spatial experiences and spatial anxiety after rather than before the experimental task(s).

Vanessa: We could explicitly manipulate stereotype threat – priming participants with masculine, feminine, or neutral identities. It would be interesting to see what brain activation changes happen with different stereotypes are primed. Or, as an alternative to inducing stereotype threat, we could manipulate confidence level. As noted in the first paper, Estes and Felker (2012) suggested shaping group-based performance by manipulating confidence in mental rotation tasks. They found men scoring higher on confidence than women, with confidence predicting accuracy across both genders. A sex/gender difference in mental rotation performance was nonsignificant when confidence was controlled for.

Sigrid: In the studies with children and adolescents discussed in the first paper, confidence and self-assessed anxiety are better predictors of performance or of preferences for environmental strategies than sex/gender.

Vanessa: Spatial anxiety could be assessed (pre- and post-test) (Ramirez et al. 2012). But then we will have to worry about priming our participants to respond differently if they guess the purpose of the study (not unusual when questionnaires are used). (Note: if stereotype threat is manipulated, we must keep in mind that spatial anxiety scores after the task may interact with stereotype threat induction.)

Our discussions suggest that research on spatial stuff would benefit not only from the consideration of the effects of group-based stereotype threat, but also from the consideration of participants’ confidence levels and spatial anxiety. The implementation of this goal involves various methodological and ethical decisions, for example, whether motivation and confidence should simply be assessed as correlates via questionnaires or should be manipulated as independent variables. Similar questions arose in our discussion of the role of experiences.

3.3.2. Plasticity: Previous Experiences, Malleability, and Training in Spatial Stuff

Brain structure and function can change as a result of specific training regimes or general opportunities for practice (see the first paper). Consequently, studies on spatial stuff performance can benefit from the acknowledgment of pre-existing experiences as well as the trainability of spatial stuff, which also offers opportunities to investigate neural plasticity.

Vanessa: A questionnaire could assess spatial experience using such specific indicators as number of math/science courses taken and other relevant formal education experience; current and past occupations; previous experience with this or similar tasks; previous experience with playing sports, building things (model cars, dollhouses, playhouses, etc.), or playing jigsaw puzzles or video games; and how far they ranged from home as a child. For longitudinal and training studies, these measures could be taken both before and after training.

To obtain further insights into the role of experiences, we consequently focused on the idea of investigating the effects of training, which also reflect the group’s common interests in learning, gender socialization, and plasticity.

Annelies: I think it could be really informative to include a temporal aspect (i.e., do a training study), since previous work has shown that predictors can relate to spatial performance in different ways before and after training (e.g., studies showing that men/boys outperform women/girls before training but not after training, but also a study that shows that testosterone predicts mental rotation – in interaction with sex/gender – before training, but not after training). Thus, including a temporal aspect by manipulating current experience adds another layer of complexity if it shows that the interactions that we are studying are dynamic – that is, that the relative weights of the interacting factors can shift.

Diana: Longer, multisession periods of training could also provide an opportunity to investigate mechanisms related to socialization, which can involve the differential reinforcement of specific behaviors that may result in different learning experiences and spatial stuff outcomes. We could think about simulating aspects of this by experimentally manipulating relevant dimensions of the training experience.

Sigrid: The question of conducting training tasks opens up more questions. If I aim to focus my research on the development of strategies in environmental cognition (instead of testing competencies in mental rotation), what could be an appropriate simulation? One possibility could be to use virtual simulations of landscapes or mazes and develop wayfinding games by navigating cursors through the landscapes. We could assess strategies in using landmark, route, or configurational cues after the training task by measures of narration of map drawing, as I did in my real-world studies (Schmitz 1997, 1999).

The variability of particular learning histories (such as video game playing), or trainability of spatial tasks, offers an opportunity to acknowledge the demonstrable plasticity of spatial skills. Training protocols, in particular, may be a way to move away from the dominant narrative of spatial ability as fixed and to instead focus on how spatial ability can be improved. Additionally, training or experience as a correlate of spatial skills or training as an experimental variable could help break the associations between spatial cognition and masculine versus feminine styles of thinking and allow for the incorporation of spatial strategies as well as competencies.

3.4. Dismantling Spatial Stuff Tasks: The Role of Specialized Mental Rotation Tasks and the Consideration of Strategies

Our discussions about potential experimental tasks in hypothetical studies centered around the question of whether to assess an isolated aspect or more complex expressions of spatial cognition. We specifically discussed the utility of the widely used mental rotation task (MRT) and issues that pertain to navigation and spatial strategies.

3.4.1. Assessment of Spatial Performance; Mental Rotation as an Appropriate Proxy?

The MRT is a prominent measure of spatial stuff (also see the first part of this paper) that is often touted as indicating an important and fixed sex/gender difference, with a moderate to large effect size. In the context of devising a preregistration protocol, we discussed the advantages and disadvantages of including MRT in a hypothetical study.

Gina: The MRT is often taken as an index of spatial skill and is a task where men on average commonly outperform women. Yet this sex/gender difference has been shown to disappear with when spatial tasks other than the MRT are used. Assuming we might take a bridging approach to our suggested revision of this research topic, it would be appropriate to maintain the use of the MRT, in order to demonstrate the effect of the additional, contextual variables and alternative means of analysis we propose. But, in addition, we should incorporate one or more alternative methods of assessing spatial skill to act as a comparator to the standard MRT.

Vanessa: We are interested in the real-world significance of MRT performance and whether it is related to, for example, science and math ability; anxiety; choice of career; wayfinding/navigation, etc. It could be that the MRT is just a human-created task that has no applicability to anything we would encounter in our actual lives. The answer to the question of what MRT performance is related to leads in different directions: (1) If mental rotation does relate to important domains (science and math ability, wayfinding/navigation), then how do we proceed with investigating it and its relationship with gender? (2) If mental rotation does not relate to important things (science and math ability, wayfinding/navigation), then we should focus on something that does matter.

As these excerpts suggest, including an MRT could serve to critically evaluate essentialist approaches and their proposed implications by discussing existing research in the light of the findings of a social-context-informed investigation. However, the observation that MRT performance is often construed as a fixed trait rather than a potentially malleable skill warrants further investigations into the tests’ reliability and validity. In addition to addressing this problem in preliminary and pilot investigations, spatial stuff research may benefit from a stronger focus on other dimensions of spatial skills, for example, related to mental maps and navigational strategies.

Some of the literature discussed in the first paper suggests that spatial strategies (that pertain to, for example, mental map development) may offer more organic conceptualizations of spatial cognition than a sole focus on MRT performance scores. Parts of our discussion therefore involves the question of how to measure strategies in a social-context informed project.

Vanessa: To address the concern that researchers invoke strategies based on sex/gender stereotypes to explain supposed differences in brain activation (Bluhm 2013a, 2013b), we can ask participants how they solved the mental rotation problems to assess cognitive strategy. We can also assess their self-reported spatial stuff self-efficacy.

I am not sure we need an analysis of the cognitive components of the MRT, especially if our intervention does not involve training in specific strategies (that is, we may be interested in what strategies participants use but not train them to use specific strategies). We are also rethinking what is involved in spatial stuff, which may be overly influenced by gendered expectations (males are better, here are the components of how males approach the MRT, so here are the components of mental rotation). Perhaps our new framework may result in a revision of the cognitive components. 8

Sigrid: If, as an alternative to mental rotation, we focused on strategies in environmental cognition, we could take games in landscape navigation as a virtual simulation of wayfinding. Maybe it would be easier to find cues for strategies here, but it should also be possible for mental rotation tasks (Krendl et al. 2008). Additionally, there are some registration batteries to self-assess spatial anxiety and spatial strategies (Schmitz 1997; Lawton 2010) and there are possibilities to assess home ranges, spatial practices and strategies with maps and outdoor practices (Schmitz 1999). This would comprise a battery of participant factors that interact with gendered experiences, the latter then acting upon strategies developed in spatial orientation.

The excerpts from our discussions show that the investigation of spatial strategies can range from post-experimental self-reports to self-reports obtained during the experiment to more complex multidimensional measures. The examples also show the entanglement of methodological choices in our exploration, which also plays a role in our considerations about how to address the question of markers for neural correlates of spatial stuff.

3.5. The Special Case of Neuroscience and Spatial Stuff Research: Considerations Pertaining to Hormones

Current narratives in scientific and nonscientific cultures suggest that hormones can have a place in the research of spatial stuff, but we had slightly different positions on what that would mean for a specific study. A first position was to revisit hormone research under the concept of the “gender-testosterone pathway” (van Anders et al. 2015), which proposes that social influences, and their interaction with other factors that may already show sex/gender differences, stimulate testosterone production, which in turn may affect spatial cognition. A second position relates to these points but calls for an emphasis on the notion that viewing hormone levels as a mere function of sex/gender variables bears the risks of further essentializing.

The first position emphasized that research on spatial stuff that includes hormonal assessments should acknowledge and investigate influences of social and cultural experiences on hormones, which may in turn affect spatial stuff.

Sigrid: Hormones, particularly the so-called sex hormones, are at the core of attempts to legitimize sex differences as biologically determined. Therefore, it is tricky to research with steroid hormones and not to fall into the trap of reifying essentialisms. Nevertheless, numerous recent studies have shown more complicated interrelationships amongst social interactions, hormones, and behavior as opposed to the traditional hormone-to-behavior linear model. For example, recent neuro-endocrinological models embrace regulatory functions and feedback loops of body-brain hormonal processes (see Montoya et al. 2012 for review) and the influence of social interactions on hormone levels and behavior (Booth et al. 2006). Sari van Anders et al. (2015) have demonstrated the situated social modulation of individual hormonal levels, such as that the experience of power increases testosterone levels in females.

Consequently, an experiment that includes sex hormones should focus on social context in addition to sex/gender as a point of departure. Pre-post measurement over tasks/trainings could be a starting point. For me, that would mean leaving gender variables aside for the first analysis of data, and instead trying to extract relevant other (social) categories that could explain the reciprocal influence between hormonal levels and performance/strategies.

We also briefly discussed general considerations that pertain to the implications that the inclusion of hormones would have for the study’s design.

Gina: The hormones discussion was part of the interchange about getting away from the standard male/female classification, a binary, categorical independent variable. I wondered how difficult it might be to get hormone levels for participants as a continuous (in the statistical sense) variable instead. My feeling is that what we propose is complicated enough without getting into details about hormones as well.

Diana: I think we may want to further specify the hormones about which we are talking. I am inferring from the context that we are likely focusing on those hormones that have been construed as sex hormones (e.g., testosterone) rather than, for example, adrenaline or cortisol (which could also be relevant in this context). I agree with Gina that it may be a bit much to also include hormones. Given that we already have a lot of potential variables, we may want to consider the logistics of including hormones in the design (e.g., time and method of assessment) and how to deal with the psychophysiological complexities and interactions, further noted below, additional in-/exclusion criteria, and control variables.

In the context of our hypothetical study, I am not convinced that there is any benefit in assigning to hormones the role of a sex/gender-related predictor or even a stand-in for binary sex/gender operationalizations without further specifying how exactly this would relate to spatial stuff. Both baseline levels and the change in hormones depend on and interact with numerous other physiological and psychological variables that may be entangled with, but are not automatically functions of, birth assigned sex or current gender identity. Therefore, and because there already is intriguing theoretical and empirical work that shows that the “reliance on pre-theory linking high T with masculinity misses the scientific boat (Adkins-Regan 2005)” (van Anders 2013, 2), I think it may be redundant to include hormones as sex/gender markers in the present context.

I would argue that if we include hormones, this decision should first and foremost be based on theoretically or empirically founded hypotheses that pertain to their psychophysiological function in the specific context of our study. For example, the Steroid/Peptide Theory of Social Bonds (S/P theory, van Anders, Goldey, and Kuo 2011; van Anders 2013) and related research suggest that testosterone is a marker of competitive situational cues. If we assume that spatial skills are socially desirable abilities, it is reasonable to expect that spatial stuff study contexts involve such cues. Therefore – to elaborate on the pre-/post-measures Sigrid referred to – change in testosterone levels could, for example, be an interesting candidate for a marker of competitive responses in spatial stuff studies. Similarly, some aspects of spatial tasks that we discussed, such as stereotype threat and anxiety, may point to cortisol as a marker for social evaluative threats (see, e.g., Dickerson and Kemeny 2004), which may make this hormone no less relevant than testosterone to our study, even though it is not socially labeled as a sex hormone. So, although I am not opposed to including hormones in a study on spatial stuff, it makes more sense to me to conceptualize them in regard to their psychophysiological role in light of the spatial stuff study rather than seeing them as a function of sex.

Although the debate on the need and adequacy of including hormonal-social influences in spatial stuff research remains an open point in our discussions, we agreed that the existing literature on the relationship between hormones and social context may be a promising source for considerations in the investigation of spatial stuff.

3.6. Considerations on Design of Data Analysis

The potential advantages of preregistration protocols include their emphasis on the specification of designs of data analyses. In addition to the design- and analyses-related considerations raised in the previous sections, we discussed how the complexity of social context-informed perspectives could be accounted for by implementing data-driven, rather than stereotype-driven, exploratory analyses. Comments in this section are popcorn-style on different promising analysis strategies.

Annelies: About the design: I think we would all agree that, ideally, conceptualizing and studying the (gendered) socialization of spatial competence involves actually tracing developmental mechanisms and processes through time. Thus, longitudinal analyses are needed, in contrast to the current overwhelming focus on snapshot, single-time studies.

Gina: It makes most sense to me to start by replicating an analysis pipeline from a study that asks the same kind of questions as us (i.e., a multivariate analysis of person and performance variables). I particularly like the one of Hoppe et al. (2012), using multiple linear regression analyses (stepwise) that allowed them to simultaneously assess the effects of three relatively independent factors on the neurofunctional correlates of mental rotation.

This pipeline could be adapted to incorporate additional interactive factors and the repeated measures arising from the training variable. I think it best to use standardized packages like Freesurfer/AFNI/SPM in order to be able to address replicability issues (unless there is evidence that there is some kind of difficulty with the package, e.g., no volume correction, etc.) At this stage, I assume we would carry out both region-of-interest and whole-brain analysis – connectivity would be great, but I think we would have to sacrifice the raft of variables we would like to incorporate – or run several different studies, which would be a whole different story.

Sigrid: Setting the focus on strategies developed in a network of sociocultural influences also opens up another debate. The context-dependent variety of strategies challenges simplified categorizations. Approaches that do not set one category or a battery of multivariate categories as a starting point for the statistical analysis of differences could instead develop clusters of spatial stuff groups a posteriori, i.e., from the data of reports of self-related spatial anxiety; motivations; gender, race, and class identifications versus rejections; and experiences and strategies.

Gina: It is worth noting that many of the issues identified here could be addressed by acknowledging different ways to test for the effects of different variables. Classical statistical approaches, or frequentist techniques, such as we have been discussing here, test for the probability that the data acquired via a specific experimental protocol fits a predetermined model. In a spatial stuff experiment, for example, the model being tested might hypothesise that the biological sex of an individual would determine their MRT performance, with other variables eliminated or controlled for. Researchers collect data from male and female participants and test for the probability that any differences found were, indeed, due to the sex variable and not just a chance occurrence. It is possible to assess the effects of multiple variables, but with this approach, evaluation of the statistical results is still based on a priori assumptions.

Bayesian approaches, on the other hand, allow researchers to identify models that make the best predictions about the data generated from a study, and also allow for models to be updated as new data accumulates. It is possible to assess the weighted contribution of one or more variables to any observed outcome – for example, to see how much combination of a high score on a spatial anxiety test and hypoconnectivity within certain parts of the brain might predict a poor performance on an MRT task. Instead of a priori assumptions about which are key variables, these would be identified by the predictive weightings given in the best-fit model. As the complexities of spatial stuff research emerge, a Bayesian approach could well get us away from many difficulties associated with the pre-experimental choice of variables that we are seeing here. 9

3.7. Broader Contexts: Accounting for the Social Embeddedness of Research on Spatial Stuff

The previous sections reflect the assumption that, in principle, spatial stuff research can be improved in ways that would reduce bias on both a scientific and a general societal level. However, spatial stuff research itself is embedded in complex societal contexts. In addition to the feminist epistemological concerns we expressed above, our discussions sparked broader science-political reflections about the fact that the societal context of research can introduce new forms of bias, even if the intent of the research is progressive. Our assumptions and discourse indicate that the potential for preregistration processes to help to improve spatial stuff research by means of sex/gender-informed protocols is intertwined with the standards of scientific education, the review process of research proposals, and the impacts on publication strategies.

Diana: Conducting quality control at preregistration may increase the pressure to adhere to some scientific standards. However, it does not automatically address the problems with such standards and conventions, or the organizational conditions of universities, ethical review boards (or lack thereof), and funding organizations. Focusing on preregistration as a solution to bad science may redirect a substantial part of the responsibility to ensure and improve the methodological and ethical quality of research from, for example, educational institutions to external reviewers. If researchers’ primary motivation to improve their methods is publication, then the best that we might hope for would be to maximize adherence to existing methodological criteria that are (at least formally) considered to be the standard for scientific studies. However, approaching phenomena such as spatial stuff with a social-context informed perspective may actually require a more profound evaluation of contemporary interpretations of concepts such as validity, reliability, causality, and replicability. Preregistration on its own can likely not provide room for such progress in sociopolitical climates that limit access to sufficient (both conventional and critical) methodological and ethical education and exchange while simultaneously exerting economic pressures that encourage “quantity over quality.”

4. Summary and Conclusions

In thinking about how to improve research practices in spatial stuff, we came from very different disciplinary and theoretical backgrounds and brought with us different research and social value goals: social power relations, ethics of intervention, feminist philosophy of science, and acknowledging but not overselling plasticity findings. These concerns were sometimes interrelated and sometimes led to contradictory theoretical and methodological considerations. Our conversations centered on how sex/gender is related to the study of spatial stuff and how to reimagine that relationship, which has practical implications for experimental design. In turn, this concern was related to the question of how a social context framework could replace mainstream, essentialist research. Similar to Fausto-Sterling’s (2005) approach in her research on the multifaceted and interacting factors of social, cultural, and biological contexts on development of osteoporosis, our discussions underscore that a comprehensive research protocol of all factors would be beyond the scope of a single realistic research study but would require a step-wise program-based approach. We acknowledge that such research will be a dynamic, reflective, and iterative process, but will be a closer approximation of our conceptual understandings of spatial stuff as embedded in social context; furthermore, it should more effectively address the issues that a social context approach to spatial stuff will require.

4.1. Expanded Network of Variables of Interest in a Social Context Framework for Studying Spatial Stuff

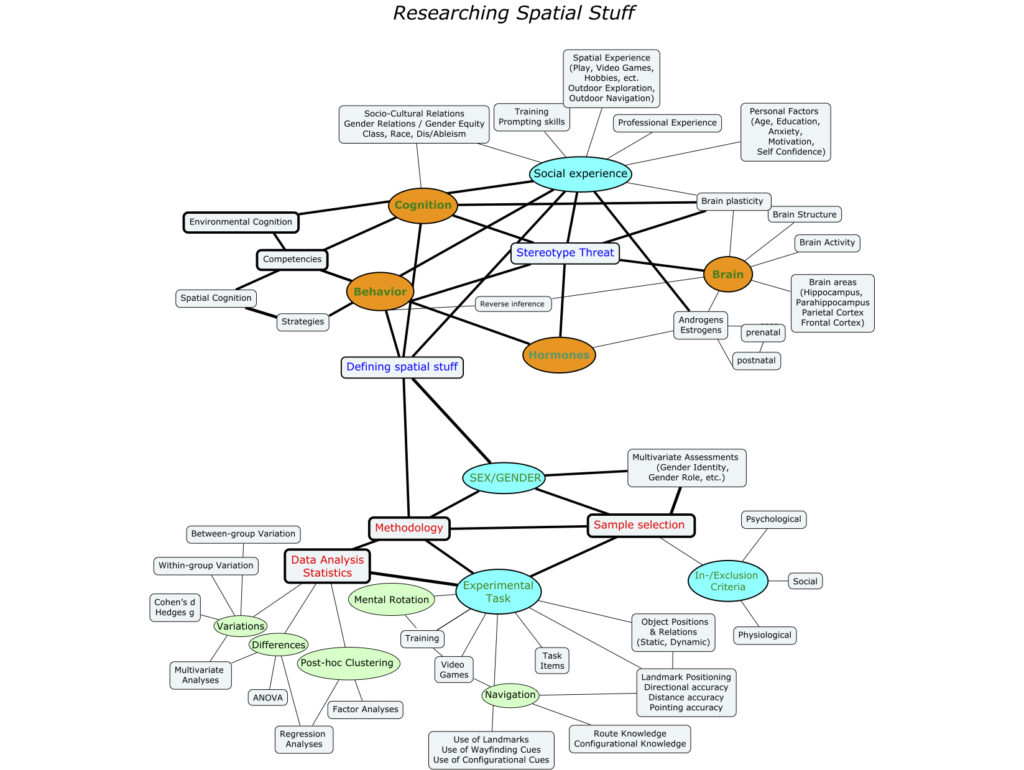

In the first paper (and see figure 1 above), we identified a number of variables that need to be considered. As a result of our conversations, we have extended the figure to illustrate the methodological implications of investigating such a multifaceted model (see figure 2).

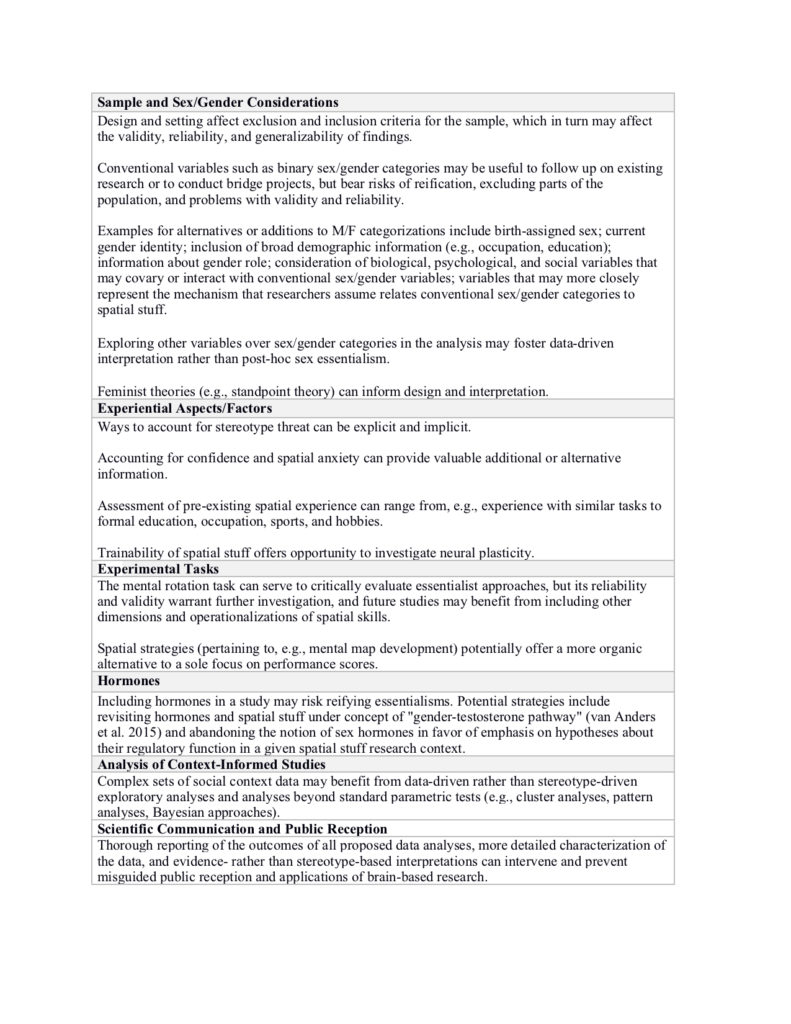

We considered the ways in which spatial stuff has been investigated at both the brain and the behavior level, raising concerns about potential confounds introduced by the tasks and measurements themselves. Our discussions involved several overlapping key areas of decision-making in the creation of social-context based spatial stuff research protocols, which we summarize in table 1 to offer some preliminary considerations that may precede the designing of a feminist neuroscience study and to present a range of partially contrasting perspectives to investigators, reviewers, or otherwise interested parties.

Table 1 Early (dissensus) considerations for social-context-based research into spatial stuff.

Rather than representing the consensus of our group, table 1 summarizes a collection of considerations that can be used to extract starting points for the evaluation and design of studies on spatial stuff.

4.2. Concluding Remarks

In the spirit of reflection that we hope will better inform future research into spatial stuff, our final conversations were to share our impressions of the process we had been through.

Vanessa: Although I hoped to come away with a solid, if ambitious, experiment design that we could, in principle, execute, I now recognize that we need to do a lot of philosophical, theoretical, and methodological work first. I think this manuscript is a good start for reconceiving spatial cognition and separating it from sex/gender assumptions. It is going to take time to start to fill in knowledge gaps left by research grounded in sex essentialist assumptions. Finally, I found it immensely illuminating, challenging, and rewarding to work with others with different research goals and disciplinary and theoretical training. I was forced to confront my assumptions and identify gaps in my understanding.

Annelies: Our interdisciplinary, dissensus-based exploration of spatial stuff has moved us away from the question of whether women’s and men’s brains are different. Instead, we engaged in a conversation that critically addresses questions of when, why, how, and in whom we may observe cognitive/brain differences – and what these may mean. Our commitment to making dissensus explicit forced us to dwell on several important questions and decisions, which illuminated our personal knowledges, assumptions, and commitments. This made explicit some of the theoretical and practical hurdles that need to be taken in order to arrive at a concrete research proposal that truly moves beyond an essentialist framework.

For me, a main reason to inquire deeper into spatial stuff has been to envision a better understanding of how spatial competence comes to be distributed (un)equally across different individuals and/or groups. Our argument has been that this requires (among other things) careful examination of variability and plasticity. These concepts are tied not only to empirical but also to deeply ethical concerns: Who has access to spatial training? Whose responsibility is this? Who benefits the most from spatial training? Which opportunities are afforded by spatial competence? Even though we have focused mainly on empirical questions, I believe our collaboration shows how a neurofeminist perspective equips us to consider empirical and ethical questions that surround spatial stuff in tandem.

Gina: This was a very useful exercise for me in that it became a process of putting my money where my mouth is. I have been involved in several commentaries that urge researchers to follow feminist informed practice, but this was a real wake-up call as to just how difficult this might be. It made me realize that many of my automatic decisions about empirical research come from years of working in an essentialist framework. It is clear that we have some way to go before an actual study or set of studies will be finalized but being engaged in the narrative en route has been invaluable.

The most rewarding part of the debate for me was the discussion about whether we should plan a bridge project or an out with the old, in with the new project. These discussions really set the context for insights into the difficulties, both theoretical and (for me, most importantly) practical, of overcoming the essentialist approach and embracing a social contextualization one. I found the different perspectives that the team offered on this issue invaluable.

Sigrid: In my view, the consensus/dissensus debates of our group reflect those necessary steps that – although time consuming – could integrate a reflective and constructive neurofeminist approach into behavioral and neuroscientific research of spatial stuff, embedded in sociocultural power relations. Coming from a feminist materialist perspective (Barad 2007), I would like to deepen the discussion to address questions that pertain to the researcher’s responsibility and accountability. From this perspective, brain plasticity should be discussed as an intra-active becoming of agential materiality (structural, functional, hormonal), social constructions and cultural norms, experimental enactments, and meaning-making processes. “Intra-action” refers to the mutual effects that all these variables have on neural and behavioral development. In other words, to experiment on and measure something changes matter and meaning.

Grounded in an onto-epistemological perspective, a careful analysis of spatial stuff has to deal with these multifaceted and entangled intra-actions. Feminists, who have celebrated plasticity for years now in order to argue against sex-essentialist standpoints, must also recognize the truth that neuroscience experiments necessarily entail intervening in the brain of an individual, and this carries responsibility. That is, spatial stuff experiments such as brain-training participants with the hope of showing particular plasticities touches questions regarding the researchers’ responsibility for the effects of their experimenting. Participants should be informed about the possibility of long-lasting modification of their behavior and neural pathways, and they should have the opportunity to give or deny consent to it. Moreover, the neurofeminist community should discuss whether, in contexts in which women and men do gender in separate social roles, it is ethical to develop in women patterns of brain activity and spatial stuff that are considered the purview of men.

Diana: To me, our project turned out to go beyond the exchange of critical perspectives on spatial stuff research. It also illustrates some of the challenges and opportunities of interdisciplinary feminist collaboration. I, too, approached the project with the expectation that the aim was to design (a potentially modest, yet concrete) study. Thus, my primary concerns included the identification of specific research questions; a design that considers the entanglements of constructs like spatial stuff, social context (including sex/gender), and scientific methods; and the consideration of non-normative and marginalized experiences and bodies. I was surprised to see how our socializations as scientists and as individuals generated a much broader discussion. Our standpoints and social positions not only come with different languages and knowledge, but also different method(ologie)s, communication styles, and structural necessities. I appreciate that we attempted to allow for dissensus in our discussion. Yet, I wonder if what is perceived as dissensus is sometimes an expression of differences in terminological and methodological conceptualizations and interpretations of similar phenomena, including those pertaining to research practices.

To me, these observations indicate that feminist-informed research may benefit from pursuing collaborative strategies that aim to bridge not only gaps between essentialist and nonessentialist perspectives on spatial stuff and sex/gender but also those between theoretical and practical perspectives. Furthermore, such strategies should aim to examine and translate the cultural, linguistic, and methodological assumptions in different fields. Apart from these technical aspects, I hope that future feminist or queer explorations of spatial stuff or other constructs pertaining to abilities and skills will seek out opportunities to more explicitly acknowledge aspects of social contexts beyond the narrow, yet often presumed, norms of, for example, being able-bodied, cisgender, heterosexual, white, and/or having secure access to resources.

Sex/gender difference research is popular. Supposed sex/gender differences in mental rotation continue to be valorized as markers of essential differences and explanations for the underrepresentation of women in STEM fields, which aid in the oppression of women-identifying individuals and/or individuals whose gender does not align with their birth-assigned sex. Therefore, we, from our different disciplinary and theoretical perspectives, have attempted to reimagine research that overcomes the usual sex difference approach. We do not claim to have exhausted the problem space, but our negotiations – displayed, at times, as consensus, and other times as dissensus – reveal a number of places where revised conceptualizations and practices may result in a more complete, and less oppressive, understanding of spatial stuff.

Our hope is thus that research on spatial stuff will be diversified, and that these interrelating concerns will be acknowledged in the design and public reception of future studies. The framework of considerations discussed in this paper may serve as a valuable resource for such efforts.

Bibliography

Ainsworth, Claire. 2015. “Sex Redefined.” Nature 518, no. 7539: 288.