|

Elena Glasberg,

"Blankness in the Antarctic Landscape of An-My Lê"

(page 4 of 6)

On the contrary, Lê asserts the links to capital flow in Fuel

Storage McMurdo, seeming to have anticipated the headlines about the

price of oil. The increased volatility of oil prices has negatively

affected planning and funding of the very NSF program that sent

Lê, in 2008, to photograph these barrels of oil, which, in the

present climate, represent a completely fossil fuel-reliant

economy.[8]

Oil barrels, full and stored or empty and abandoned, have, since the

1930s when a concerted U.S. effort to colonize Antarctica began, been a

stock image of Antarctic stations.[9]

Where a clearing of tree stumps

once marked the passing of wilderness, the fuel storage tanks tell

similar tales of the technology and resource needs for human being. The

massive effort to create permanent structures in a wilderness is nowhere

more dramatic than at the South Pole, where nothing survives but ice,

and everything, from toothpicks to neutron detectors, must be flown in

from the north at great effort and cost.

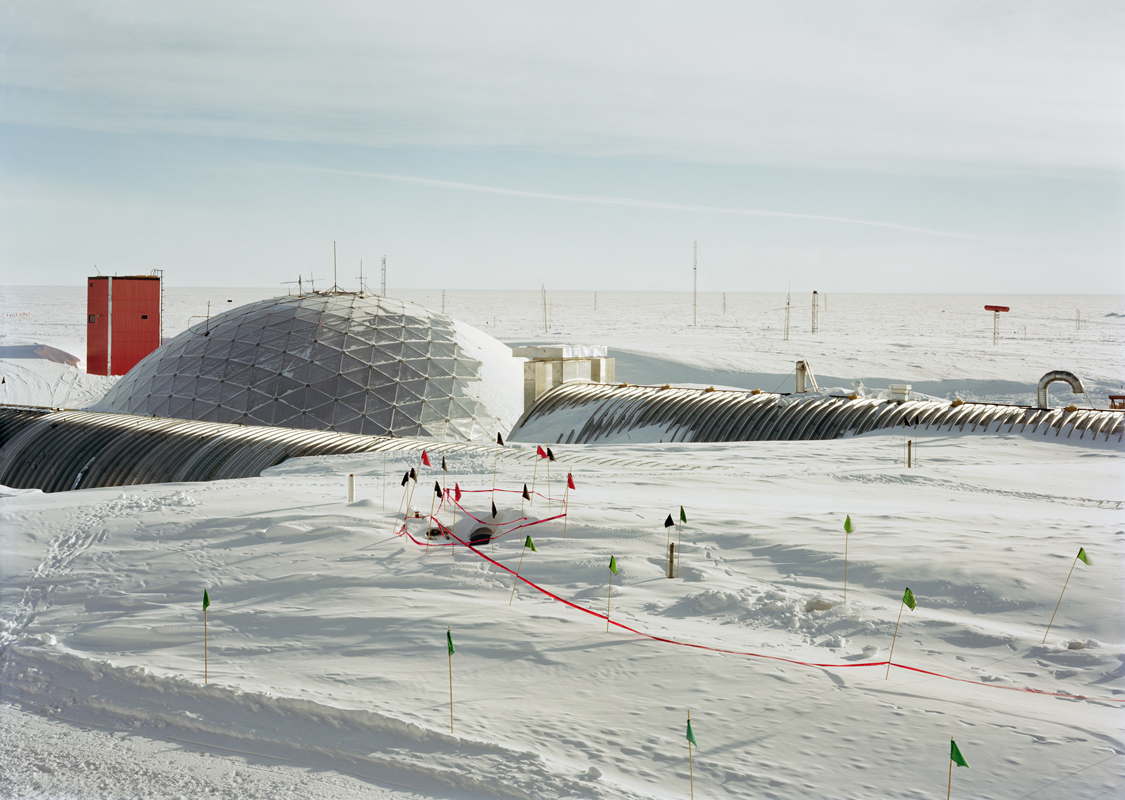

Figure 4 An-My Lê

Abandoned Dome, South Pole, Antarctica, 2008

Archival pigment print

40 x 56 1/2 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy Gallery

The built environment at the South Pole, though relatively

circumscribed and brief in duration, is nevertheless deeply marked by

U.S. cultural projections. How many people know that a Buckminster

Fuller geodesic dome, or a "Bucky Ball," is slowly being buried in the

ice of the south pole, after having been planned in the late 1960s and

completed in 1973 and shielding inhabitants and supplies until 2007?

Lê's image of the sunken dome that once carried Fuller's utopian

vision of "spaceship earth," is reminiscent of Tacita Dean's

"Fernsehturm" series on modernist architecture. Sue Hubbard describes

this series as "encapsulat[ing] a lost historic vision and an optimistic

belief in a now defunct social system."[10]

Marks of everyday

inhabitation such as flags and footprints and bright tape take on an

almost macabre feel in the merciless frame: this is a ruin of a

futuristic ideal, now obsolete and trapped in ice. The "deadpan"

framing places the dome and viewer on the same plane, emphasizing the

harsh juxtaposition of human and built environment. Lê's

photography of the built environment at the South Pole emphasizes the

obsolete, the Fordist prehistory of heavy machinery and the footprint of

what I will call the "U.S. Heroic Age" of Naval operations beginning in

1929 and ending with the development of the International Polar Year and

the ATS in 1959. While the U.S. brokered the ATS and its international

safekeeping of the territory from claims, the period of the U.S. Heroic

Age nevertheless resulted in the U.S. effectively and solely colonizing

the Pole by building the first permanent station in the 1950s, then the

Bucky dome in the 1960s, and now the third generation of super-sleek

corporate-style station, completed in 2008 and almost ostentatiously

omitted by Lê.

Instead of the new station, Lê investigates the failed and

inaccessible, incomplete, or buried traces of the built environment.

She works against the coffee table book aesthetic; her images are

enormous, not meant for containment between covers, no matter how

glossy. Her high art and highly technical images negotiate between the

landscape aesthetic that broke down at the Pole and the more vernacular

aesthetic that visitors to, and inhabitants of, the South Pole have been

attempting to reestablish. The photography of Emil Schulthess, with its

use of fish-eye lenses to reflect in the mirror ball of the ceremonial

south pole and its emphasis on sun dogs and other unusual weather

phenomenon, is a form of updated "ponting" (after Ponting's carefully—and

to Scott's men intrusively—staged perspectives).[11] The

extremophile exceptionalism has through repetition and circulation

(particularly on the internet) become an ironic if normalizing

repertoire of representations of the polar plateau.[12] Lê focuses

instead on the industrial infrastructure, the chaotic, menacing, and

wasted space of an unredeemable blankness very different from both the

blank of imperialism's hope and the desert of Porter's conservation

aesthetic.

Figure 5 An-My Lê

Storage Berms, South Pole, Antarctica, 2008

Archival pigment print

40 x 56 1/2 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy Gallery

More significant to Lê than the new station is the lost and

discarded, the incoherent epiphenomenal and un-beautiful, as in Storage

Berms at South Pole. Lê labels the photo using the argot of the

U.S. base as it has derived from its Naval origins. The term "storage

berm" refers to an earthwork or a mound formed as a result of human

labor, as in the berm walls of a fortress or of mounded earth in a

garden. But the South Pole is neither fortress nor garden; and the term

berm can help to understand how culture in the form of language and

built environment is being reshaped in Antarctica. "The berms" in

'Polie' patois refers to the entire storage area on the near perimeter

of the central encampment consisting of the Dome, new pole station, and

out buildings. An extensive sprawl of plywood platform covered with all

sorts of off-loaded cargo forms an almost city-like network of streets.

The berm area is like a warehouse without sides or a roof. The bermed

platforms require an intensive regime of shoveling to retain their

integrity. Far from the "city center" of science or logistics, the

berms are the domain of mostly the lesser skilled workers, who are

assigned their maintenance. It is on this shunted yet essential sprawl

that Lê chooses to center her image, turning away from the central

pole. If there can be a "backside" to a circumlocated pole, the berms

are it.[13]

The image lacks contextualizing features beyond a rudimentary and

conventional sectioning into sky, horizon line, and foreground of ice.

Lê destabilizes this overbearing classical perspective by mixing

elements of motion and stasis. Through the overlay of compositional

features, Lê also questions the very usefulness of perspective, of

relative motion, tracking, and lighting. Despite the bright sunshine

and the classical composition, the viewer hardly knows where to focus

within the enormous frame. The perspectivally broad, flat and

multi-focused approach refutes the unipolar cliché and seems to be

saying that there is more here in this basic land-sky polar plateau than

is generally considered; the pole becomes in this way more like other

sites on earth—and in history—than in the extremophile tradition.

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

Next page

|