Memoir and Academics

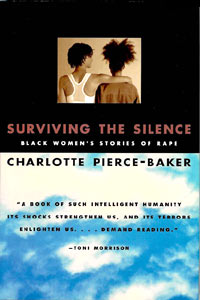

With the publication of the book Surviving the Silence: Black

Women's Stories of Rape, my personal life was understandably

changed. But also dramatically altered was my academic/professional

life. Surviving the Silence and its being in the world has

reshaped my pedagogy. The writing of memoir and its dissemination has

shifted my thinking about "theory." There was always tension for me as I

began to write. I felt as if I were forced to make a choice of which

audience to "write for" - to speak to.

With the publication of the book Surviving the Silence: Black

Women's Stories of Rape, my personal life was understandably

changed. But also dramatically altered was my academic/professional

life. Surviving the Silence and its being in the world has

reshaped my pedagogy. The writing of memoir and its dissemination has

shifted my thinking about "theory." There was always tension for me as I

began to write. I felt as if I were forced to make a choice of which

audience to "write for" - to speak to.

I believe if we are to broaden the categories of what we call "the

academic" and challenge those "sacred boundaries," books such as

Surviving the Silence need to be read, critiqued, and fit into

the pedagogy of and about women, especially within the arena of black

women's literature and pedagogy. Colleagues across the nation interested

in issues of trauma, violence, and black women's lives (writers,

scholars, filmmakers, activists) are now more than ever working together

to develop a "language" for writing and teaching in the areas of rape,

sexual assault, and other traumas. Many of these colleagues, men and

women, have graciously used Surviving the Silence in their

college and university courses. Doing so, I believe, encourages a more

expansive pedagogy on the university front. Each time, for example, that

I use Dartmouth University professor Susan Brison's academic memoir,

Aftermath, or practicing psychologist Martha Manning's

professional memoir, Undercurrents, or Duke University professor

and colleague Karla F.C. Holloway's personal yet academic treatise,

Passed On - when I recur to these texts - I know I am shifting

and expanding the parameters of trauma, literature, theory, and the

"lived lives of women."

Graduate-student scholars have been some of my most ardent

supporters, analyzing and critiquing in their classes the text

Surviving the Silence. Now I better understand what I

accomplished by writing through memoir; I can now evaluate the

process as well as the consequences of many of my writing

decisions.

It was in 1990 that I began to think about writing what

eventually became (in 1998) the book Surviving the Silence: Black

Women's Stories of Rape. The book's foundation was extremely

personal: that is, it was motivated by my own rapes, rapes perpetrated

by two black males - burglars, in my own home - as the legal version has it:

"rapes committed in the process of another crime." In spite of that very

personal beginning, my initial thinking on the content of the

book I was writing was to produce an academic piece on rape,

slavery, black men and women, and the impact of sexual violence on black

lives. After all, I was an academic; therefore, I told myself, I should

write something totally academic - footnotes, bibliography,

allusions - the whole academic bundle! My research began with the idea of

producing - in book form - an "ethnography of black rape." With this focus,

all seemed to be taking shape-gaining purpose, I thought. And I began to

interview black women rape survivors. The audiotapes increased in

number. However, as I interviewed the women, I soon became patently

aware of two things: one: I was not writing, and two: I was in

denial about my own rapes. I was surely procrastinating (or what we, in

the field of trauma, sometimes call "paralyzed by fear"). I had

unraveled an incredibly intricate string of secrets and continued

silences - and I was at the center of it all. My realization became

clear: I was still "in hiding" and not openly talking about my own

wounding. I had, thus, failed in the face of the first goal of

writing memoir: truth telling. If I had failed at truth telling,

then, how could I possibly face "objectively" and in supportive ways the

other women and their narratives? The answer was, I couldn't - nor should

I ever have thought I could. In fact, the actual writing (that is, words

on the page) of Surviving the Silence did not begin until I had

"owned up to" my own rapes, the details, the aftermath. It was almost as

if I were not allowed to transcribe the words of the other women

until I had "faced myself." It was at this juncture I realized - I was

creating community. And in such a community one must share "the

unspeakable." Mine was no longer a solely academic endeavor. And it was

then that I remembered feminist scholar Carolyn Heilbrun's proclamation

that "it is not so much women's lack of language as their failure

to speak profoundly to one another" (emphasis mine) (Writing A

Woman's Life, 43). And with that, my fingers gained strength!

|