Not an Academic Memoir

This is the first time in a long career that I've found myself

writing and radically rewriting, then yet rewriting a talk for a

conference. The reason, obviously, is that I am not comfortable with the

conference topic; I am the wrong speaker to invite for this particular

subject, "Academics and Their Memoirs," because up to the moment of the

invitation I had never associated my memoir with the life of an

academic.

This is the first time in a long career that I've found myself

writing and radically rewriting, then yet rewriting a talk for a

conference. The reason, obviously, is that I am not comfortable with the

conference topic; I am the wrong speaker to invite for this particular

subject, "Academics and Their Memoirs," because up to the moment of the

invitation I had never associated my memoir with the life of an

academic.

Yet, perhaps it is inevitable the memoir should have been so

categorized; after all, it was written in response to an assignment and

was published by a quasi-academic press, the Feminist Press, housed in

the City University of New York. Florence Howe, then publisher of the

Press, was also a CUNY professor, and in assigning the memoir to me at

an MLA convention, she had turned to Tillie Olsen, whom she had just

introduced me to, to say, "Tillie, Shirley will write her memoir for

us." This dramatic announcement made it impossible for me to reject

Howe's assignment, for Olsen was and still is a highly reverential

figure for me and for multiples of women readers to whom her book

Silences paradoxically motivated us to break silence and to

write. Would my memoir possess its feminist articulations if it had been

written for another publisher and without taking dictation from Olsen's

collective indictment against women's silencing?

If my memoir has a formal and ideological source, however, it was

neither Howe nor Olsen but Carolyn Heilbrun's text, Writing a Woman's

Life, and Nancy Miller, that served as its tutors. Miller, in her

role as an NEH faculty mentor, had said to me in 1988, impatiently, in

response to my hesitation at coming out as a scholar and writer, "Well,

what are you waiting for?" And once I had received my assignment from

Miller, then from Florence Howe and Tillie Olsen, I found in Heilbrun's

1988 text explicit directions on how to write my woman's life.

Permission, legitimation, direction: these conditions prevail in

academia as the student embarks on her studies; so, yes, indeed, how

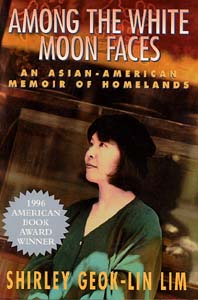

else to think about Among the White Moon Faces but as the memoir

of and by an academic?

And yet, at a fundamentally ontological level, I refute that

characterization. I am mortified, horrified, to be read as an academic.

Gertrude Stein, in Everybody's Autobiography, observes, "That is

really the trouble with an autobiography you do not of course you do not

really believe yourself why should you, you know so very well that it is

not yourself, it could not be yourself because you cannot remember right

and if you do remember right it does not sound right and of course it

does not sound right because it is not right. You are of course never

yourself."

|