Who Counts?

Qualification 1. Being qualified 2. A modification or restriction; limiting condition 3. Any quality, skill, knowledge, experience, etc. that fits a person for a position, office, profession; requisite 4. A condition that must be met in order to exercise certain rights.

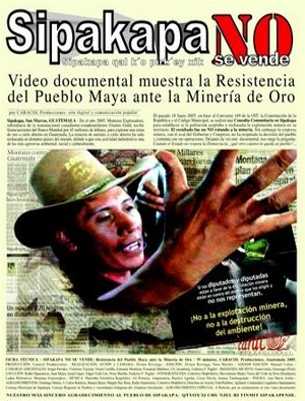

In some ways a consulta is quite simple. Townspeople are brought together and asked a straightforward question with a yes or no answer, like, “Do you want mining in this community?” Then you just add up the number who say yes and the number who say no and the answer with the biggest number wins. In Sipakapa the counting was done by hamlets, so there were several moments of making the plurality of inhabitants into a one (in one hamlet 70 said yes, 200 said no, so the no wins), then each hamlet’s yes and no were added together to get 13 1 hamlets said no, one said yes, and one abstained, and so all those people and votes translate into “Sipakapa says No!” “Sipakapa is NOT for sale!” This was then translated into slogans on banners and shouted at demonstrations. The latter is the title of a film made about the process. 2

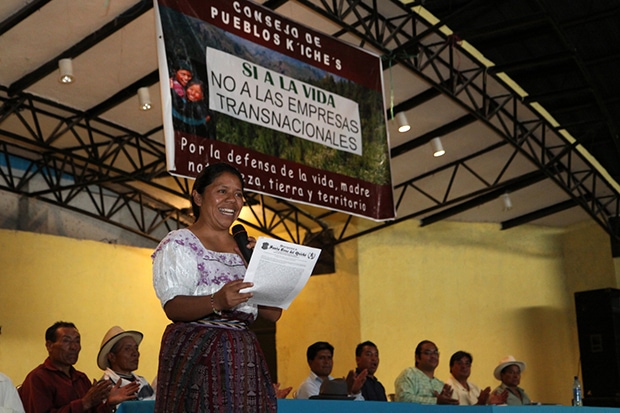

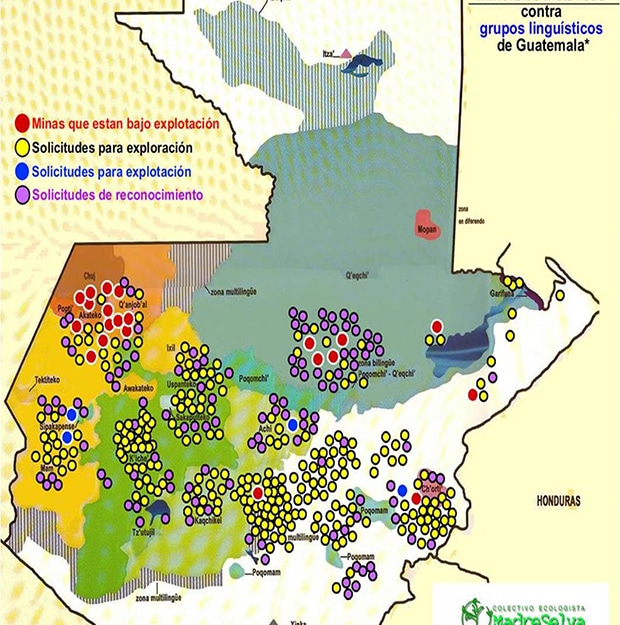

I suggest that this experience of counting and the accompanying technologies of perception—the film and maps of mining concessions for example—are being constituted as biotechnologies. Through many people’s labors they have leached out of the tiny isolated village of Sipakapa and assemble people (literally) under the banner of Yes to Life, No to Transnational Companies.

So that, many miles away, over the mountains in Santa Cruz del Quiché, Lolita Chávez, a Maya-K’iche’ woman, can say they began to hear rumors about the consultas, “We kind of heard about what was happening in San Marcos, Sipakapa, but that was there, far away. In 2007, I think, someone showed the video about Sipakapa, but we didn’t really have any relation to it, except to feel sorry them. Pobrecitos, their hair is falling out! We never thought it could happen in Santa Cruz! But then in 2008 or 2009 an economist came to talk to us and he showed us a map. We were mapped! We had no idea, but he showed us, in full color! How much of Quiché had been signed away for exploration. You can’t believe the impact that had on us. It was super impactante. Now it wasn’t about being in solidarity with people over there, but it was right here, we had to defend ourselves! Things began to flow, there was a corriente de consultas, an information boom, a stream of consultas, and we needed to be part of it.”

But it wasn’t easy! In Sipakapa, four years after they did theirs, and while eating lunch (donated by COPAE) after a workshop on alternative development, an elderly man explained, “for the consulta, the mayor was GANA (the ruling party at the time). He was under heavy pressure from the party and from the mine. But we all got together. Everyone was against the mine. In my hamlet, it was about 300 of us, and we all signed. We voted by signing. Only the adults, if not we would have had many more. It was a happy day. We felt good. Only one hamlet voted yes because their auxiliary mayor was with the mine and he pulled a lot of people that way. We all came together from all the hamlets to present it to the mayor and he wouldn’t sign off. We pressured and pressured. We held him there ‘til two AM! (laughing) But finally he did. Then we sent a delegation down to the city to present it to the government.”

One stormy night, on a bus full of national and international antimining activists grinding along the dirt roads encircling the mine and connecting Sipakapa with San Miguel, two men told me the story of their own consulta in nearby San Ildefonso Ixtahuacán in September 2007. “It took about one and a half years from when we started. It took lots of organizing. We already have a mine and we realized we couldn’t touch that, but there are licenses for three others and we had to stop them. The mine is open sky and the mountain doesn’t exist anymore. We can’t plant. Nothing grows. So we had everybody, the auxiliary mayors, the development commissions, all the religions are affected, so we worked with the pastors, the teachers, the Ex-PAC, we all have to be together.” Even in the dark they sensed my reaction to their mention of the PAC, the wartime paramilitary civil defense patrols. He explained, “we were all in the PAC and there were PAC massacres there. They did bad things. But now it is mostly progressive. The Ex-PAC were great, they have people everywhere, 5,000 men! We assigned tasks and they did everything. People talk badly about them but they really helped with the consulta. All in one day we had 35 centers and 14,000 people came. We had CEIBA [an NGO], national youth groups, and Mayan organizations, they all sent observers. We did it. The people said no.”

I haven’t participated in a consulta but in accounts and videos the festive air is palpable. The masses of people are really impressive, with long snaking lines of people waiting to be counted filling the central square, kids playing, music, the bonhomie of a gathering and collective purpose. “It was a happy day, we felt good.” But while the observers were there as representatives of audit culture, part of the “rituals of verification,” 3 they were also present because, as Aniseto said, people know they are “against a gigantic power, a global economic power.” Although it officially ended in 1996 the war still hovers close, as does more recent violence. In 2005, government troops opened fire on protesters blocking the Panamerican highway to stop a huge cylinder destined for the mine. One man was killed, but to date there have been no prosecutions. Far more macabre, in June 2007, in a hamlet close to the mine, a little girl found the headless body of Pedro Miguel Cinto, a 60-year-old Mayan man and antimine activist. A few days later the head was found across provincial lines in Huehuetenango and returned by the Montana company, “causing uncertainty and panic among his neighbors.” 4 The circumstances of his death have not been clarified. Then, in May 2010, two unknown men came to the door of Diodora Hernandez, a single mother living near the mine. She became an activist when they built part of a school on her land without permission. The men asked for something to eat (standard practice in hamlets without a restaurant), but she had nothing to sell. They insisted, just some coffee? Please? So she agreed but as she was serving them, one pulled out a gun and shot her in the head. Hermana Maudilia told me later: her children were screaming and screaming and the neighbors got her taken down to San Miguel. She was bleeding everywhere! It was clear she needed better care so they sent her first to San Marcos and then to the capital. Fortunately Rigoberta Menchú stepped in and helped with the medical side, the money, and the press. Diodora lost her eye and is still recovering, but she walked out of the hospital on her own. Once again, no one has been charged for this crime.

So, counting yeses and nos is “simple” addition, but when people band together to be counted, they do some pretty complex calculations of risks. They know they are playing long odds.

- Which, as Katherine Fultz 2009 reminded me, is an auspicious number for many Maya.[↑]

- Caracol Productions, Sipakapa NO se vende: Resistencia del pueblo Maya ante la minería de oro, (Guatemala, 2005).[↑]

- Michael Power, The Audit Society: Rituals of Verification, (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997).[↑]

- ADISMI (Comunidades en Resistencia and Asociación de Desarrollo Integral San Miguelense), Los impactos negativos de la Mina Marlin en territorialidad Mam y Sipakapense, (Guatemala: ADISMI, 2007): 32.[↑]