This is an adaptation and expansion of my opening remarks for the Police Response to Violence panel at Invisible No More on 3 November 2017. The goal of this piece was to provide a concrete and succinct example of the myriad ways that policing and the criminal legal system do not provide justice, safety, or support for marginalized communities, including queer and trans people of color, immigrants, survivors of violence, low-income people, people with disabilities, and so many more.

In 2005, I conducted my first intake at the Audre Lorde Project, an organizing center for lesbian, gay, bisexual, Two Spirit, trans, and gender nonconforming people of color in New York City. A strikingly beautiful Black gay man walked into my office and sat down in front of me. He was furious and scattered.

I need to know that you will help me. I need a lawyer. I think I have multiple lawsuits.

At that time, there were few parties for Black queer and trans communities in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. Yet on Sunday nights The Lab, an event space, hosted one for Black gay men. A few months before entering my office, Alex 1 had attended one of these Sunday night parties. After a few hours of dancing he left the party and made a stop at Popeye’s.

Because fried chicken is the perfect accompaniment to a sweaty night out.

On his way out of the restaurant a few men approached him, started to yell homophobic slurs, and then physically attacked him. Somehow, in the midst of being beaten, Alex was able to grab a garbage can. By swinging the can at his attackers and yelling at the top of his lungs, he was eventually able to escape.

I thought it was over. I thought that I was safe.

He hadn’t noticed that a few New York Police Department officers were walking west on Fulton Street toward him. When he saw them, he assumed that they were there to help him seek medical attention and press charges against his attackers. Instead, they began to question him. Irate, traumatized, and in physical pain, Alex became frustrated with the officers. The situation escalated and later that night he found himself in handcuffs at the 79th Precinct, where he was attacked again – this time by the New York Police Department.

At that point, I didn’t have a lot to offer Alex. He didn’t know the people who attacked him on the street, and whether or not he would ever meet them again. I offered him a few legal referrals, but he did not receive much support in his cases. I called The Lab, learned that it didn’t have security who understood how to create safety for queer and trans communities, and was asked if we could provide bouncers or training. We fundraised for Alex’s medical bills, which supported him in the short term but which we both knew wasn’t a long-term solution. I told Alex that we hoped to build more in the future, and that we were forming a group of queer and trans people of color who wanted to create our own safety outside of the police. Despite his anger and exasperation at me, at the situation, and at the system, Alex became one of the early members of the new Safe OUTside the System (SOS) Collective at the Audre Lorde Project.

Alex’s incident, and many others that followed, inspired programs and projects that allowed the project to offer more support. We eventually created the Living against Violence Fund, which allowed us to support many survivors with expensive medical bills or missed workdays. Two years later we hosted our first Safe Party. Safe parties are spaces where party organizers were supported to create safety plans and strategies to address violence and harassment, including from law enforcement. After my time, the project and its learnings led to the Safe Party Toolkit, which helps party organizers think through strategies to address violence and harassment, including from law enforcement, within and on the way home from clubs and parties. 2

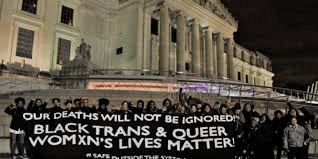

Alex’s experience was the first incident of violence around which I organized. I was new to the anti-violence movement and new to working within my community. I had a history in economic justice and had just come from a few years of organizing low-income childcare providers. Those women were brilliant, bossy badasses, but that work allowed me some distance and emotional separation. So when Alex walked in, I didn’t know that both of our lives were about to change. I didn’t realize how invisible, and how ignored, we were as queer and trans survivors of violence. I didn’t realize that we were going to have to learn de-escalation skills to intervene in the violence that we faced, because we did not have other people to call on that we could trust. I didn’t know that eventually those de-escalation skills would grow into the Safe Neighborhood Campaign, where we recruited and trained local businesses and organizations to prevent, intervene, and provide support for survivors of violence including, but not limited to, queer and trans people of color. The first workshop that the SOS Collective created was titled after the closing line of June Jordan’s “Poem for South African Women”: “We Are the Ones that We’ve Been Waiting For.” 3 And it’s the truth: addressing the violence that we face – whether it’s homophobic or transphobic, sexual, within our relationships and families, or from the police and government – is often left up to us.

I feel so grateful that Andrea J. Ritchie documents both our survival and our resistance in Invisible No More. 4 Despite the ways that many current activists and organizers can speak to intersectionality, organizing that focused on police violence against trans and gender nonconforming people and women of color was often forgotten. Instead, organizers working on police violence focused on the experiences of straight cis men of color and mainstream anti-violence organizations focused on the safety of straight cis white women. Whether the survivor was a nonbinary gay Black man like Alex, a Black queer woman, or a Black trans woman, our stories, our actions, and, for many of us, our lives’ work, remained invisible.

When we talk about the violence that affects Black women and trans and gender nonconforming people, we have to expand the site and context in which this violence occurs. Most people with multiple oppressed identities experience higher rates of violence. Yet our society has entrusted the police, the most violent force it has, to be the first responders. To center these survivors’ experiences, we must shift the strategies that we use to address violence and harm. I believe that brilliant creations come out of exclusion, and that some of our most vibrant and inventive strategies to address the intersection of police violence, hate violence, and interpersonal violence have come from Black queer and trans communities. I am grateful for all of us who have created community safety strategies out of the need to survive. And I am humbled and inspired to cocreate a future, alongside survivors like Alex, that centers the safety of Black queer and trans communities.

- Alex’s name has been changed for privacy.[↑]

- The Safe Party Toolkit is a collection of strategies generated by three generations of SOS members and staff to build safety in party spaces without relying on the police or state systems. Over twenty SOS members wrote it collectively over five years and it was supported by Audre Lorde Project staff members including Ejeris Dixon, Che J Rene Long, and Tasha Amezcua.[↑]

- June Jordan, “Poem for South African Women,” Passion: New Poems, 1977–1980 (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1980).[↑]

- Editor’s note: Invisible No More author Andrea J. Ritchie was a member of the SOS Collective for several years, contributing to workshops, the Safe Party Toolkit, and “know your rights” materials. She documents and highlights the Audre Lorde Project’s groundbreaking work challenging police violence and criminalization at the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and criminalization, dating back to 1997, in Invisible No More and Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States, coauthored with Joey L. Mogul and Kay Whitlock (Beacon Press, 2011).[↑]