As I now see it, my memoir is based on growing up in the South. First of all, what that might do to you. But secondly – and way under that – what it might, in the long run, do for you. What kind of feminist can an inbred Southerner be, wherever she ends up living? Isn’t that learned restraint, ingrained politeness, understatedness and all that contradictory to any outspokenness such as feminism requires?

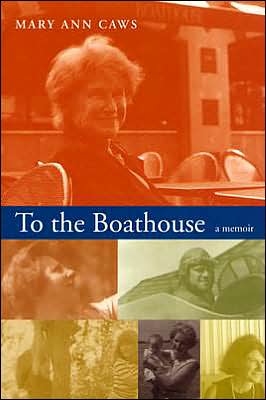

Carolyn and I discussed this, sometimes straight on and sometimes glancingly, in our weekly walks over the many years in which I was writing To The Boathouse. She wanted very much to have our picture together in it, and there it is. The two-of-us-plus-dog picture, which serves as a background for an announcement of this conference, was taken by Jim, and I love it dearly.

That’s not the one in here. The one in here is one where we’re both doing things at the MLA, and that’s a choice of the editors. In a sense, anything I say now or read now has to do with that background – the background of walking with Carolyn in the park, and talking about the things we talked about. So I dedicate this talk to her, naturally.

Our discussions often turned around the topic of Southern-ness. As for what the South, or any South or my South, might have done or keep on doing for you, the main thing is probably that very contradiction itself – between the way you were brought up and the way you have, then, to bring yourself up.

Ironically, and just as precisely, that’s what can’t be put into words. It can’t be spoken and named, only written. Some things I couldn’t write either. For instance, what Carolyn always wanted me to do – she always wanted me to talk about class difference in the South. I can’t. Not that I wouldn’t, but I couldn’t.

What I could tell most efficaciously concerns my klutziness, if I may borrow that term from my New York friends. Carolyn loved best my weekly stories of my mishaps and forgetfulness and awkwardness – all odd tales of the oddnesses in my disorganized living, so different from hers.

Perhaps I overstated those tales for her. Perhaps I overlived that part of my living for her. I would greet her expectant face every week with some new story of my awkwardness. Actually, a great part of my memoir, which you will hear a little of, is about that: Losing my place, my slides, my credit cards, my identity. Losing my text somewhere in Australia. Losing my way somewhere in the Saskatoon snow. Missing the plane to Winnipeg or to Paris. That sort of thing.

Accidents, incidents – it’s not anything deep or true; not at all like the basis of my beingness, which is a kind of drivenness. I always want to be somewhere else. I always want to write somewhere else. I want to do something, always, that I haven’t done – choose a new subject, be a new subject. I’ve always called that dilettantism, but I’ve been told to say it’s just energy. (laughter)

I still think it’s dilettantism. That’s always been my truest place. Memoirs want to be about truth, don’t they? Even as we arrive at that through such peculiar means, including fiction. So I had to write about love and betrayal on both sides of a very long marriage. How do you do that without rage or bitterness or self-indulgence?

I gave this my best shot and I hope it comes over, despite all the fictionalizing of fact or embroidery of memory or undone overstatement of incidents and accidents and whatever else. After the fact, I and many of us tend to call it history.