Queerness and “Monstrous” Silence: Achy Obejas’s Memory Mambo

This kind of choreopoetic thinking is crucial to queer Afrodiasporic women artists writing toward the transcendent “nuance” that Shange finds at the border of body and voice. One example is Achy Obejas’s 1996 coming-of-age novel, Memory Mambo. Like for colored girls, Obejas’s text is often read in terms of its political interventions, with less attention paid to its work at the level of form. Obejas takes up the kind of choreopoetic logic Shange introduces, using fusions of body and voice to highlight the complexities of queer diasporic women’s identifications—their “galaxies” of thought, feeling, and connection—in the space of the prose fiction page. Where both versions of for colored girls emphasize the transformative potentials of embodied voice, Obejas uses choreopoetic thought to show the danger that the silencing pressures of “monolith[ic]” identification holds for queer women’s bodies in diaspora. 1

Memory Mambo tells the story of Juani Casas, a lesbian-identified woman coming of age in a working-class Cuban and Puerto Rican enclave of Chicago at the close of the twentieth century. Juani’s story is narrated from an ostensibly consistent first-person voice that seems to speak Juani’s perspective. Yet, Obejas’s narration positions the character’s body as a funnel for many different and potentially conflicting voices, each articulating different perspectives on race, womanhood, and identity. Early in the novel, the narrator states: “sometimes other lives lived right alongside mine interrupt, barge in on my senses, and I no longer know if I really lived through an experience or just heard about it so many times, or so convincingly, that I believed it for myself—became the lens through which it was captured, retold, and shaped.” 2 Juani identifies her perceptual anatomy as a “lens” through which several voices—queer, straight, masculine, feminine, Cuban, American, and others—speak their contradictions through her, the narrator’s body.

It is Juani’s multivocal body that allows her to understand the complexities of her own racial and ethnic identity within her queer Afrolatina community. 3 She describes her Puerto Rican lover, Gina, as a “self-hating queer” who believes that “being a public lesbian [would] somehow distract… from her puertorriquenismo.” 4 Gina imagines her racial identifications in direct tension with her sexual identification, remarking: “that’s so white, this whole business of sexual identity. But you Cubans, you think you’re white.” 5 Thus, for Juani, “[i]t didn’t matter that all our friends, and eventually my family, said our names together Juani and Gina, as if it were one word—juanigina—because the bottom line was simple: Gina wasn’t out.” 6

This tension between racial allegiance and the expression of queerness interrupts both Juani’s view of her body and the form of Obejas’s text. Like Smoke and Graciela’s “tactile” erotic talk in “Two,” the amalgamated nomenclature of “Juanigina,” introduces the queer possibility of embodied speech. Juanigina signals two voices in one body—a specter of female Afrolatinidad in which disparate political perspectives and national identifications can be resolved through a queer intimacy instantiated on both corporeal and linguistic planes. Juanigina names the fantasy of a contrasting voices and ideologies joined through the body and its pleasures. Yet for Obejas’s characters, silence disables the choreopoetic potential of this formulation. Where Smoke and Graciela’s vocal merging demonstrates transcendent erotic black female possibility, Obejas illustrates the damage that befalls queer diasporic women unable to escape “sequester in the monolith” of single-issue representation. 7 The presence of homophobia and Gina’s decision to privilege national and ethnic representations over the nuanced expression of her sexuality render their relationship impossible, and obliterate juanigina’s radical possibility. Thus when Gina’s friends accuse Juani of being a “gusana,” or “bad Cuban,” partly because of her insistence on being out, and Gina says nothing in Juani’s defense, this psychic rift prompts a violent physical fight that produces several parallel ruptures in Juani’s narration. She states:

This is the part where I left my body…

All the screaming had dissolved into a high-pitched hum interrupted only by the thud of a fist on muscle, the labored work of our angry lungs, and the crack of an elbow or leg hitting bone.

All of the blood pours savagely from my limbs, all of my limbs are severed, veins sliced open, blood blinding—and here you are, teeth bared, blowing air—I go this way then that, push you away, hit you, bring you to me… feel, again, your muscles stretch underneath my bones, my bones crushing your bones… blue/black/magenta—my blood like a fountain…—and I kiss you… gums, teeth, down your throat, then we both gasp and choke and spit—and I love you, monstrously and uselessly…. 8

This fusion of voice and body—the dissolution of screams into the sounds of colliding flesh—mobilizes choreopoetic thought to illustrate the violence of ethnic and racial “monoliths” and the danger silence holds for queer bodies. Juani’s efforts to reconcile her own perspective with Gina’s speech (or, more precisely, with her refusal to speak about sexuality) result in an explosive physical confrontation that destabilizes boundaries between self and other through voice. The two women’s bodies merge into sound in Juani’s narrative, their voices becoming an undifferentiable “hum” of violence and voice. As the passage’s sentence structure scatters to accommodate the many differences at play, the narrative point of view also shifts to carry the characters’ stories into a fluid present tense. This shift provokes the novel’s only instance of second-person address. Juani’s “you” (in “here you are, teeth bared, blowing air”) is a relatively open signifier, hailing not only Gina’s body, but also the larger presences of xenophobia, homophobia, patriarchy, racism, sexism, and other violently oppressive forces that interrupt queer Afrolatina sexuality and love. Escaping this intersectional melee requires a chorepoetic intervention of negation: Juani declares she must “leave her body” to break out of the scene as her voice itself “crack[s]” under the weight of racial monoliths and sexual norms.

“Visual Fusion” and “Textual Impairment”: Zanele Muholi’s “What do you see when you look at us?”

While the queer legacies of choreopoetic thought may be most clearly visible in the works of diasporic poets and prose writers, the formal melding of body and voice opens important pathways for black queer visual art as well. The work of South African lesbian photographer Zanele Muholi illustrates the resonances of choreopoetic thinking for queer visual artists in the diaspora.

Muholi’s 2011 mixed-genre text, “What do you see when you look at us,” compiled with queer South African poet Pam Dlungwana and Namibian-born poet Olivia Coetzee, demonstrates the usefulness of choreopoetic thinking for articulating the links between body, voice, and black queer women’s subjectivity on the visual plane. Part visual chapbook and part photo essay, the text is comprised of portraits of black South African lesbian women and poems exploring black queer female experience. The poems and images are collected under headings that flag specific aspects of queer life such as “On Poverty,” “On Blackness and Body Politics,” and “On Race and Representation.” Muholi terms the text a “visual fusion,” following Shange not only in developing a new genre for exploring Afrodiasporic female sexuality, but also in naming that genre as both an amalgamation of and an extension beyond other recognizable forms. Muholi’s generic invention of the “visual fusion” echoes the logic of the choreopoem by highlighting the epistemological properties of the image of the black queer female body, but also insisting that even the poems themselves should be read as “visual” texts.

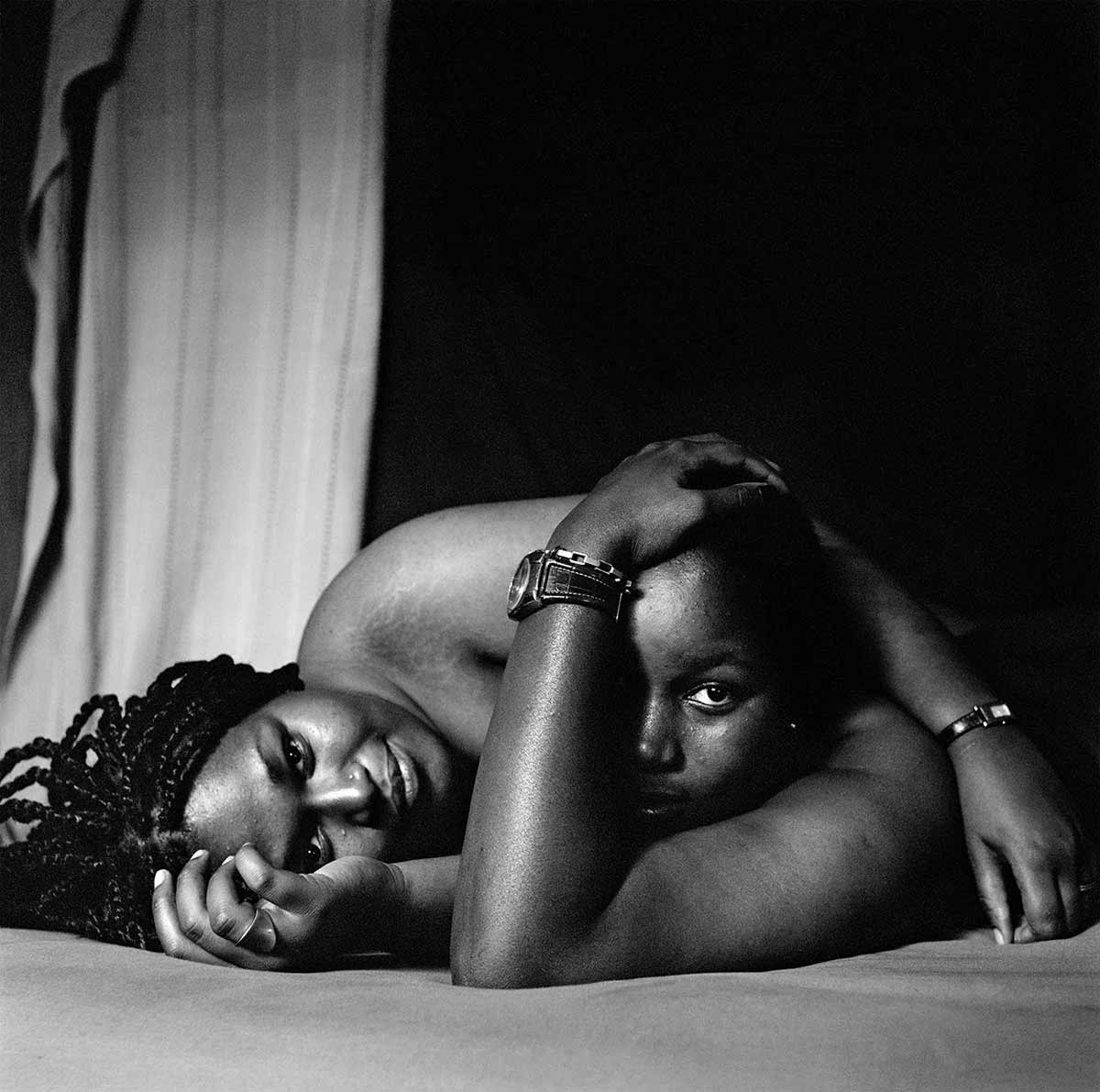

Zanele Muholi et. al. (2011). 9

“What do you see?” begins with a section titled On Black Lesbian Youth, which opens with a photo from Muholi’s Being series. The image shows two black women laying in a bed, entwined in each others arms as they look frankly at the camera, one smiling, the other’s face partly illegible, cast in the shadow of her arm, which cradles her own head. The greater part of the women’s bodies, too, is unintelligible through basic technologies of vision; light and shadow compel the reader to imagine the touch of the women’s flesh as it continues in the background of the front-lit scene. This image, however, is followed by the poem “Caught,” written by Dlungwana, a free verse poem describing an experience of erotic black queer intimacy through a metaphor of captivity.

Because of its stanza structure and its use of whitespace, “Caught” bears reproducing in full:

inherited

from lovers past

fist full of fury

new lust birthed,

a sweet decay of

inhibition and doubt

gently creaming into

warmth eminating from

a heart now residing

between thighs

greedily holding I captive,

Captured. 10

The speaker of “Caught” remains unidentified until the last of the poem’s three stanzas, in which she describes “warmth eminating from/ a heart now residing between thighs/ greedily holding I captive/ Captured”. The “I” serves a function similar to the “language intricate and tactile” that Shange’s Smoke and Graciela speak; the speaker invites the reader to engage the sensory and sensual aspects of black queer women’s love unmediated by distancing pronouns—or the obscuring shadows of the visual; only after scenes like the one pictured in “Being” have been conjured does the poem’s speaker announce itself.

And, as in Shange’s “Two,” the poem’s form echoes its body/language. Dlungwana’s line breaks and the collaborators’ choice to arrange the poem at the center of the page evoke both a curved human form and the letter “I” that lays unspoken at the poem’s center. The visual fusion thus positions the poem itself both as a textual signifier of an individual black queer woman subject and as a body open and available for reading. By articulating the physical embrace the poem describes in terms of an erotic captivity, Dlungwana uses this ambiguous “I” to write narratives of black female sexual subjectivity that are erased, as Spillers puts it, in moment[s] of colonial, imperialist, and perhaps even psychic “capture.” The fusion of image and text here reimagines capture as a moment of mutual erotic exchange between black women, a subversive instantiation of the kind of “sheer sensual pleasure” around which both Shange and Spillers define black women’s subjective nuance. 11 The poem invites viewer/readers to find subjective grounding—that is, to search for the “I”—within a subversive queer erotics consistent with Moraga’s ideas about the radical potential of sexual power dynamics in the lives of queer women of color, for example, and with Audre Lorde’s notion of radical erotic expression as a means of intervention against social dominance. 12 Following this subversive poetics through to the poem’s orthography, we might read the alternative spelling of “emanate” as part of this rewriting, a formal disturbance that reveals the “I” where it is not supposed to be, doing what it is not supposed to do.

The fusion of bodily image and text continues throughout Muholi’s “visual fusion”, requiring the reader to navigate both body and text as part of a single set of utterances about diasporic lesbian identity. The portraits that follow “Caught,” titled, “Nothing Lust For-ever I” and “Nothing Lust For-ever II,” map the poem’s poetic rendering of embodied black female sexuality back onto the plane of the photographic image.

“What do you see when you look at us” (a visual fusion). 13

The photographs, which appear under the heading “On Black Lesbians and Safer Sex,” share the composition of Dlungwana’s poem, visually rendering scenes of black queer women’s erotic pleasure, but also inserting in that image the nuanced imperatives of sexual health and responsibility, and an ethic of care shared between black queer female bodies. The composition and tonal contrast of the of the black and white image focalizes not the act of sex performed by two black queer female bodies, but the image of the white latex glove, which represents an erotic care and mutual responsibility, and the violent threats HIV and AIDS pose to black South African lesbian women’s lives. In centering the glove, the image interrupts the exclusion of black lesbians and black queer women from public health discourses on HIV/AIDS and safer sex in South Africa, discourses in which, as Zethu Matebeni points out, “[w]hile much has been written about gay men’s sexuality and its interplay in HIV and AIDS debates, there continues to be silence about female same-sex relationships and how HIV and AIDS affect women in these relationships.” 14

The photograph and the poem together work as doubly rhyming images: the photograph echoes the poem’s use of white space, positioning black queer female bodies in a visual continuity first with the form of the poem, which itself invokes the shape of a female body, and then with poem’s speaking voice—the missing capital letter “I” that both the photo and the form of the poem evoke. Reading the visual fusion for choreopoetic typographies, we can also read the arrangement of the bodies in “Nothing Lust For-ever I” as evocative of the forward slash, which, in Shange’s poetics, indicates a semiotics of both distinction and inclusion—a division of breaths and a joining of thoughts made material on the page.

Like Shange’s choreopoetic works, Muholi’s “visual fusion” trains readers in a new literacy, requiring them to come to new understandings of black lesbian subjectivity that take into account the affective and emotional nuances expressed in Coetzee’s and Dlungwana’s poems. Indeed, Muholi states that the text is “for all black women who are intimate and in love, women and transmen, regardless of their age, ethnicity, race, and borders. Ultimately, this work is for all humans who are textually impaired but able to feel.” Riffing on Shange’s title and the closing lines of for colored girls, Muholi offers a dedication that is both subjectively expansive and pointedly precise. Where Shange’s choreopoem closes with a tight circle of brown women physically joined in an intimacy of black woman “color” and nuance—the choreopoem’s climactic “laying on of hands”—Muholi opens her text by naming the absence of nuanced expression against which Shange’s colored girls dance, speak, and move. 15 She identifies the grammars of racism, sexism, homophobia, and xenophobia as afflictions of language and corporeal misreading that, she says, render viewers “textually impaired” and bar black queer women from both textual and visual histories. By blending word and body, then, she joins Moïse, Obejas, and several other recent black queer women artists in extending Shange’s choreopoetic tradition, inviting the viewer to read, hear, and see against the afflictions of text that unwrite black queer women’s voices, and to understand, as she writes in full-bodied capital letters at the close of the text: “We are here NOW!” 16

- Ntozake Shange, Nappy Edges, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991) 3.[↑]

- Achy Obejas, Memory Mambo, (Berkeley, CA: Cleis Press 1996) 9; emphasis added.[↑]

- Miriam Jimènez Román and Juan Flores define Afrolatinidad as “an expression of long-term transnational relations and of the world events” that create ethnic and racial identifications among “people of African descent in Mexico, Central and South America, and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, and by extension those of African descent in the Unite States whose origins are in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Afrolatinidad emphasizes both the African ancestry of many Latin American people and the extent to which “Latinidad and blackness are not mutually exclusive.” By considering their complex subject positions in opposition to “white” standards, Obejas’s characters position themselves within discourses of Afrolatinidad, and illustrate how Afrolatina identity intersects with various national, sexual, ethnic, and gender identifications. See Miriam Jimènez Román and Juan Flores, The Afro-latin@ Reader: History and Culture in the United States (Durham: Duke UP, 2010) 1, 10.[↑]

- Achy Obejas, Memory Mambo, (Berkeley, CA: Cleis Press 1996) 78.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Achy Obejas, Memory Mambo, (Berkeley, CA: Cleis Press 1996) 135.[↑]

- Ntozake Shange, for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enuf, (Berkeley, CA: Shameless Hussy Press, 1975) 3.[↑]

- Achy Obejas, Memory Mambo, (Berkeley, CA: Cleis Press 1996) 135.[↑]

- Zanele Muholi, On Black Lesbian Youth (from Being series), 2007, Durban, in Zanele Muholi, “What do you see when you look at us?,” 26 October 2009, Zanele Muholi (Official Website) 22 August 2011.[↑]

- Pam Dlungwana, “Caught.” in Zanele Muholi, “What do you see when you look at us?,” 26 October 2009, Zanele Muholi (Official Website) 22 August 2011. 2. Sic.[↑]

- Ntozake Shange, for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enough, (New York: Collier, 1977) 47; Hortense Spillers, Black, White, and In Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) 26.[↑]

- See Amber Holibaugh and Cherrie Moraga, “What We’re Rollin’ Around in Bed With,” Sexual Revolution, ed. Jeffrey Escoffier (New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 2003) 538-552 and Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: the Erotic as Power,” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Freedom: Crossing, 1984) 53-59.[↑]

- Zanele Muholi, On Black Lesbians & Safer Sex (from Nothing Lust For-ever I), 2007, Amsterdam, in Zanele Muholi, “What do you see when you look at us?,” 26 October 2009, Zanele Muholi (Official Website) 22 August 2011. [PDF] 1.[↑]

- Zethu Matebeni, “Sexing Women: Young Black Lesbians’ Reflections on Sex and Responses to Safe(r) Sex,” From Social Silence to Social Science Same-sex sexuality, HIV & AIDS and Gender in South Africa, ed. Vasu Reddy, Theo Sandfort & Laetitia Rispel (Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press, 2009) 102. In 2006, Muholi created the queer activism and media organization Inkanyiso, to address the erasure of queer and LGBTI people from media in South Africa and beyond, providing media, video activism, and visual literacy training to black queer and LGBTI South African youth. Inkanyiso’s site includes a broad and rich archive of narrative and video documenting black lesbian experiences with HIV and AIDS in South Africa, including video of a vigil for black lesbian HIV/AIDS activist Buhle Msibi, and Busisiwe Sigasa, the lesbian Soweto-born poet, photographer, and blogger who died of AIDS-related illnesses in 2007. See http://inkanyiso.org/category/black-lesbians-and-hiv-aids-in-south-africa/.[↑]

- Ntozake Shange, for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enough, (New York: Collier, 1977) 60.[↑]

- Zanele Muholi, “What do you see when you look at us?,” 26 October 2009, Zanele Muholi (Official Website) 22 August 2011. [PDF] 11.[↑]